Major: Architecture

Year of Graduation: 2009

Location and date of Field Experience: Salvador, Brazil (July – August 2008)

Organization: Axis Mundi Design

Project: A participatory design/build project for a marginalized settlement on the outskirts of Salvador

Hometown: Laguna Nigel, CA

Quote: To this day, I feel like I’ve been given so many opportunities because of the minor. I love the fact that everyone has their own academic and professional goals and then finds a way to integrate development work within that framework.

Tell us a story from your practice experience.

I worked with a small group to design and build a public outdoor seating area using a participatory design process. We wanted to involve the community members in every phase of the project — choosing the location, creating the design and constructing the actual project — through this process we really wanted to understand how the project could improve their living environment. After spending time with the community, we saw everyone gravitating towards a beautiful space with a view of the ocean — the kids played games, the women conversed while hanging their laundry, others played music or just enjoyed the view. We noticed that everyone sat on the ground or random pots or boxes. After drawing sketches with community members about project ideas for this location, we decided to build a concrete table with a system of overlapping benches.

Music is huge in Brazil. People are always drumming on things. We decided to build the table and benches with a built-in drum so that the kids could make music when they played on them. We put an old pot inside a concrete bench and the kids all signed their names on it. We also designed the structure to have poles with hooks so it could be integrated into the laundry system that the women already used the space for. They could hang their sheets and clothes to dry and shade themselves simultaneously.

The best part was seeing everyone help with various parts of the project; from mixing concrete, carrying gravel or helping us make the formwork for the benches, we were constantly engaging with and learning from one another. Once the project was complete, the community members threw a party with music and food. Everyone seemed so excited and welcoming. I will never forget the next day when we woke up to see kids playing on and around the structure and using the table to draw and write. Throughout the day we saw women hanging their laundry as we had hoped and various community members congregated there to play music, talk or just enjoy the day. The project really felt like a success and I will never forget the experiences I had there.

What’s something that the Global Poverty and Practice minor taught you that has influenced the work you hope to do?

To this day, I feel like I’ve been given so many opportunities because of the minor. I love the fact that everyone has their own academic and professional goals and then finds a way to integrate development work within that framework. The GPP minor is a great starting place to learn about and develop critical analytical skills to target pressing issues worldwide. Students from the GPP minor are innovators, paving the way for their self-defined careers and futures. Once I got involved in it, all of these opportunities kept coming my way and the Blum Center always provided their support. And it was with the support of professors like Ananya Roy that I received a Fulbright grant to do research in Guatemala.

Tell us about your Fulbright project.

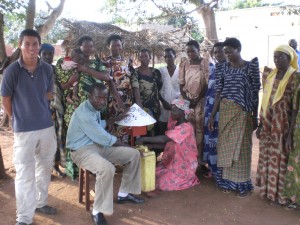

We used a participatory analysis process to coordinate community development projects in a rural Guatemalan community. After my project in Brazil, I knew I wanted to understand how to better engage communities in the development of their environment. We went through an intensive process of community meetings, surveys, semi-structured interviews, and community mobilizing in order to really understand the needs and strengths of the community. We mutually decided on developing three project scopes, each of which would address specific needs expressed throughout this participatory appraisal process.

The small scale project is to revamp an old building into an information center with computers, a library and an area to give workshops. We wanted it to be a place where the community could connect with the rest of Guatemala and access information and communication resources. For example, we suggested that local coffee farmers could use the Internet to network directly with their buyers and cut out the middle man.

The medium scale project is to help organize a women’s cooperative to start a bakery. During our meetings, women had emphasized their interest in making money for themselves as well as learning new recipes. We agreed that a bread cooperative would be beneficial for them, seeing as they currently buy bread from another community. But again, a project like this one is complex — more than we could have ever initially thought. We had to think about how to grow or buy wheat, what the altitude might permit, the soil, an oven, the skills that each woman could bring to the business as well as trainings for them to learn how to keep finances or sign their names… again, so many details.

The largest and by far the most difficult undertaking is constructing water infrastructure. The nearest water source is two hours away by foot, making it difficult for engineers to map the route, think about a pump system and electricity, where water stations will be placed, drainage, the cost of water and even politics! The minor opens your eyes to the intricacy and massiveness of every project. Nothing is black and white and there are a lot of complex pieces to this work.

What is your dream job?

I don’t know if I have a dream job in mind yet. I want to be someplace where I can expand and improve development programs and interventions. I’d love to apply for an internship at UNDP or USAID. I feel like so many already established programs are not effective and that resources are lost between these institutions and the community or non-profit they are intending to serve. I’d like to find somewhere in between where I could help resources be more well delivered.

What are you doing now?

I applied to graduate school for urban planning with a focus on International Development and will be going to UCLA (on a full-ride scholarship!) starting this fall. This summer, I participated in the Global Health and Women’s Empowerment institute at UCLA. It was one of the most stimulating classes I have every taken and I can’t wait to get more involved in such work. I’ve also been working to develop a student organization called Amazon Medical Program to bring UCLA students to the Brazilian Amazon to work with a nonprofit there who delivers health services to isolated communities along the Amazon River.