By Sybil Lewis

During her sophomore year, Rebecca Hui was still wrestling with her decision not to attend art school—and was tepidly observing her fellow students’ focus on professional careers. Through a friend, the double major in architecture and business got an internship at a landscape architecture firm in Gujarat, India. But her boss refused to let her work; instead, he encouraged her to delve into Indian culture and discover what intrigued her.

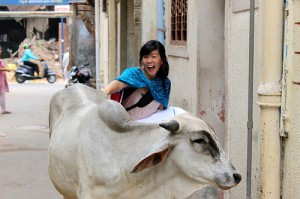

Hui decided to follow around cows.

“I was shocked by how much respect cows received in the city—they were like a bourgeoisie,” Hui said. “I wanted to know why I had trouble crossing the road, but all the cars stopped for a cow.”

In Hinduism, the cow is considered a sacred animal; and in many areas, such as Gujarat, vegetarianism is the norm. Hui’s interest in human-animal interactions was influenced by her roommate, an adherent of Jain, an ancient Indian religion that advocates a high social consciousness toward animals. Her roommate allowed pigeons to live in their home.

“She would say, ‘If we build our houses on their houses, why can’t they build their houses in ours?’ It became normal to wake up with pigeons flying around my room.”

After her summer in Gujarat, Hui decided to switch her second major from architecture to urban studies and to apply for the BigIdeas@Berkeley competition in the Creative Expression for Social Justice category. She won $3,000, enough to start her project.

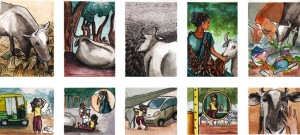

The Secret Life of Urban Animals is not a typical BigIdeas project. Hui followed cows in different parts of India to better understand their cultural significance as well as urban planning and sustainable development in the world’s most populous democracy. Upon graduation, she received sponsorship to continue the project as a Fulbright-Nehru Research Fellow and National Geographic Society Young Explorer.

Hui wrote in a July 2011 blog entry: “a system’s state can be understood by observing how molecules bounce around in its environment. I figured that in the same way, much can be revealed about the state of a changing society by following how its inhabitants, a cow in this case, ‘bounce’ around its surroundings. Who knew that following a cow could reveal so much about the city’s changing cultural, social, and even political fabric?”

Following cows in the densely populated city of Mumbai, Hui noted that people’s relationship to cows varied immensely between rural and urban areas. In rural areas, cows are integrated in everyday life and play an important role as sources of milk and farm labor; they are treated with more familiarity compared to more urban settings, where they are mainly used for commercial activities and in some cases face physical harm from people.

Hui has argued that protection of urban animals and wildlife can strengthen urban planning and public policy. As an expansion of her project, she attempted to study elephants in Tamil Nadu and leopards in Mumbai’s Sanjay Gandhi National Park, and noticed that that bureaucracy or real estate interests were often prioritized over conservation. If the elephants’ migration patterns were accounted for, she argued, then city planners could create grassy overpasses and roadways to protect wildlife, while still developing for larger human populations.

Some may see this line of reasoning as overly idealistic, especially since India is projected to replace China as the world’s most populous country by 2050. While Hui does not advocate for cows and other animals to roam freely in cities due to the health concerns, she argues that taking into consideration human-animal interactions is imperative to preserving ecosystems that humans benefit from.

|

|

|

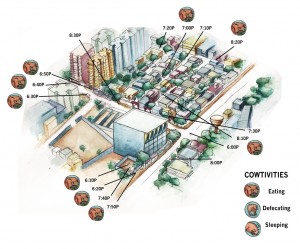

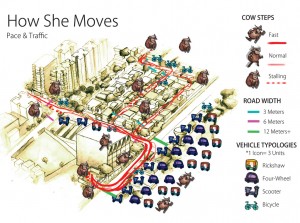

Maps that Hui drew to document how cows inhabited the city and dealt with different urban realities such as traffic. |

|

Hui admits she has never been a conventional thinker. As part of an independent research project her junior year, she decided to observe how different groups interact with Legos. She left the sets in public areas at the Haas Business School, the university’s architecture building, Wurster Hall, and a local elementary school. She found that the Legos at the business school were built into hierarchical structures, such as pyramids; the architecture students tended to make intricate designs, including Star Wars figurines; and the most creative structures came from the elementary school children.

In her undergraduate classes, Hui often put a twist on her assignments. For the business course Entrepreneurship to Address Global Poverty, her goal was to get the Cal student community more aware of social entrepreneurship opportunities on campus. The end result was a series of illustrations of an octopus, whose tentacles served as a metaphor for the reach of different social entrepreneurship opportunities.

“When she first came back with the octopus drawing, I chuckled and did not understand it,” said the course’s professor John Danner. “But the end result was much better than the original idea—she has an idiosyncratic way of putting ideas and issues together that stop people in their tracks.”

Hui just likes to search for patterns in human development and thinks that her ability to notice subtle differences in societies stem from her upbringing. Her father was a professor and during his sabbatical leave Hui moved around nine times as a child between Hong Kong, New Jersey, and Arizona, and said she learned to adapt quickly in order to “fit in.”

While the Secret Life of Urban Animals project concluded in September 2014 with a two-week exhibition of Hui’s paintings, drawings, and cartoons at the David Sassoon Library in downtown Mumbai, Hui’s work in India is far from over.

Currently, she is working to found Toto Express, a social enterprise that she says is the first design-licensing agency for rural artisans in India. During the Secret Life project, Hui met many rural artisans whom she learned were unable to generate enough income due to lack of connectivity and marketing. When they migrated to urban areas in search of employment, they ended up encountering a different form of poverty in the slums.

Hui believes it is important to create alternatives to urban migration—what she calls a “prosperous village” that can recognize villagers’ inherent skills and assets. Over eight months in 2014 and 2015, she has conducted three pilot projects with tribes specializing in the traditional art forms of Dhokra metal casting, Phad scroll painting, and Gond painting. She intends to get artisans to upload their designs to an online platform for licensing by corporations.

The platform will capitalize on the estimated $2.5 billion market of holiday gift giving by corporations and a 2014 law requiring that 2 percent of corporate budgets be allocated to corporate social responsibility. Hui hopes that Toto Express’ platform will provide a way for corporations both to meet their gifting needs and meet government mandates. In turn, artisans will benefit from growing profits that will allow them to stay in their trade and village.

“Many NGOs and craft ventures work with these artists, which is fantastic, but it seems they are often harrowed by supply chain and inventory challenges,” Hui said. “Toto Express increases artists’ incomes without having to send the artwork or artist to urban areas—which usually adds more layers to the supply chain, reducing the actual cash that artists receive.”

Moving forward, Hui is planning a fourth pilot project that would place permanent design centers in three to four villages, to help artists adapt their artwork for various corporate gifts and better use the Toto website.

“I am dedicated to this project because I relate to artists whose reasons for leaving their art spoke back to my reasons for pursuing a more ‘respected’ career path within the often risk-adverse Chinese American community,” Hui said. “But to see that happen to these communities where art is intimately connected to identity, hurt tremendously. I want to change that.”