In the summer of 2021, Patricia Quaye took a 15-hour journey from her home in Awutu Breku, a small town in Ghana, to Berkeley to be a part of the inaugural cohort of the Master of Development of Engineering program, housed at the Blum Center for Developing Economies. While she was 7,000 miles away, her heart remained close to home, and in the summer of 2022, Quaye went back to Ghana to build on her organization dedicated to giving back a better livelihood to her community.

Quaye had founded SHE 4 Change in January of that year as both a business and a foundation to provide women in her community with more opportunity; SHE stands for Support Her Empowerment. “That is exactly what the project is doing,” says Quaye.

SHE uses sustainable fashion design to empower talented rural women to break free from generational cycles of poverty while promoting rich African heritages to the world. The project helps women with years of skilled seamstressing experience who find themselves disregarded or deemed incapable due to the rural environment and a male-dominated society. These women are often paid much less than what the cost of materials and their labor are worth. SHE aims to break this cycle of poverty by paying women fairly and expanding their market. Quaye took advantage of her time as a student in Berkeley to study the global market and adjust her designs to a broader range of individual tastes while sending the profits back to women in her community. The high quality of SHE apparel extends its customer base beyond those who can only afford the simplest clothing.

Quaye recalls, from her conversations with the seamstresses, instances prior to founding SHE 4 Change where customers didn’t return to pick up their clothes after dropping them off for sewing, as they, too, were poor and may have later decided they could not afford the sewing costs after all. Some even refused to pay the previously agreed-upon cost. This leaves many women stranded.

“Imagine going through four-plus years of training to acquire a skill, but because you are located in the ‘wrong’ place and people don’t know about your skill, you don’t grow professionally, and you can barely put food on the table,” Quaye says.

Quaye’s cousin, a seamstress for over 15 years, inspired SHE 4 Change. When COVID-19 hit, Quaye saw her struggle — her cousin lost her few and only patrons to the pandemic, leaving her unable to afford even a basic meal. Quaye wanted to help and began looking for organizations that could assist skilled women like her cousin find patrons or obtain resources. But she couldn’t find any support, with many organizations unresponsive or simply declining to help. Quaye wanted to take matters into her own hands.

Quaye’s project-based classwork in the MDevEng program required her to connect more deeply to the community she’s serving. After conducting research and interviewing women, she realized this was a challenge across many regions and communities in Ghana, not just for her cousin. Rural women often lack the tools to sew high-quality garments, therefore most individuals living in big cities and urban areas, who can afford higher quality wares, don’t “believe” in rural women’s capacity to produce the quality they require, she says. This limits seamstresses to rural markets with lower rates for their work hours.

Quaye cites her own experience for her dedication to creating opportunities to break the cycle of poverty. “I grew up in a poor background,” she says. “I know what it means to not have opportunity. I know what it means to not have food on the table or know when the next meal you’re going to eat will be.”

So over the summer of 2022, along with a summer job and internship, Quaye went back home to her small town of Awutu Breku to be hands-on with her fashion enterprise. This entailed working with her mother to create designs, searching for and purchasing fabric in Accra, Ghana’s capital, from female vendors, and bringing fabric and supplies back to the seamstresses who then sewed the designs using their own machines. While SHE seamstresses can repair existing clothing, they focus on making new ones from scratch, supporting women fabric vendors as well. These fabrics are traditional African prints and patterns which hold historical and cultural significance. The SHE logo itself showcases the traditional Ghanaian symbol of the sankofa in the “E,” a bird that signifies retrieving good from the past.

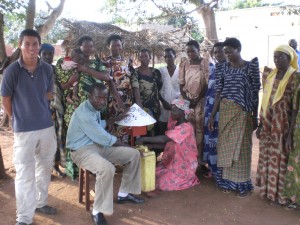

The most valuable part of her time at home, however, was the face-to-face interaction she had with her team — getting to know the women in person rather than over the phone. She had met these seamstresses through her mother, a community organizer who encourages girls to get involved in political decisions that affect them. Her mother provided Quaye with connections and further instilled the importance of empowering the women around her. Quaye shared the excitement of the project with them, learned the impact it could have on them and their families, and came to better understand her seamstresses’ work environment.

Nowadays, SHE’s piloting stage features six women, but Quaye plans to hire over a dozen more before an official launch. She officially registered SHE 4 Change as a company and a foundation, obtained a company bank account, and created social media accounts for the brand.

More challenging are the finances. Quaye had used her Berkeley scholarship stipend to cover fabric, packaging, and other production costs. But she also went looking for funding from both NGO- and government-sponsored, women-oriented organizations to provide her seamstresses with reliable machinery to guarantee a better and safer working environment. As more profit comes in from an international customer base, equipment can be purchased to lower the seamstresses’ time and effort, thereby lowering the cost of labor. This then allows for their service to be affordable for their own community as well, creating a chain reaction of relieving financial insecurity. And as the foundation grows, Quaye hopes to train more women. “It’s important that this project allows women to empower themselves, so they can empower other women as well,” she says.

Since graduating from the MDevEng program, Quaye has continued gaining experience as the sustainability coordinator at a retail company in the Bay Area, where she’s deepened her understanding of the clothing industry. In

July 2023, Quaye was awarded with the Mastercard Foundation Alumni Scholars Impact Fund, powered by the Big Ideas Contest. With this funding, she is building a SHE 4 Change Sewing Center in Awutu Breku, and in March will head back and officially launch the SHE 4 Change line of products. She hopes to get more funding through other channels to support the project. All the while, she continues monitoring the impact of education on women in Ghana and is committed to follow up with research that can expand the impact of SHE 4 Change and similar endeavors to more countries through the SHE 4 Change Foundation.

“I don’t want people to buy just to help the women, but because the women can produce quality products, and they feel the value when wearing the clothes,” she says.

Indeed, Berkeley peers and teachers who have tried SHE 4 Change’s wares have loved them and become patrons. “The support from the DevEng department, my classmates and professors, always pushes me to know I am making an impact. It is like a family that is on the same mission with me,” she says.

The MDevEng program itself has played a massive role in how she approaches her foundation, ensuring that she stays tuned to the needs and aspirations of the women on her team.

Going forward, Quaye hopes to see SHE 4 Change take off into a global brand known for empowering women while providing unique clothing. She also hopes to continue to break Eurocentric barriers by using fashion to showcase traditional African prints. Instead of having the world dig out culture and resources in Africa, she says, “we can bring the culture to the world by keeping heritage and local women alive through our garments.”

During high school, I looked unquestionably at technology leaders like Bill Gates and his wife Melinda, whose philanthropic foundation aimed to solve every apparent misfortune in the Global South. Even more, I found solace in the “giving back” days that Silicon Valley tech companies employed as a fulfillment of their corporate social responsibility.

During high school, I looked unquestionably at technology leaders like Bill Gates and his wife Melinda, whose philanthropic foundation aimed to solve every apparent misfortune in the Global South. Even more, I found solace in the “giving back” days that Silicon Valley tech companies employed as a fulfillment of their corporate social responsibility.

There is a saying in Swahili: “Maji Yaje Kwanza” which means “water is the first of many things”. The people of Mihingoni—most of whom are subsistence farmers—depend largely on rainwater for survival, but climate variability and long dry seasons continue to stunt crop yields. Low agricultural productivity decreases household income, and increases hunger. Lack of proper water, sanitation and hygiene leads to disease, and Kenya continues to have one of the worst under five mortality rates, globally. Families are forced to choose between sending their girls for water or sending them to school, and they choose water first. This limits the prospects for their future, and the cycle of poverty in Mihingoni continues. Until now.

There is a saying in Swahili: “Maji Yaje Kwanza” which means “water is the first of many things”. The people of Mihingoni—most of whom are subsistence farmers—depend largely on rainwater for survival, but climate variability and long dry seasons continue to stunt crop yields. Low agricultural productivity decreases household income, and increases hunger. Lack of proper water, sanitation and hygiene leads to disease, and Kenya continues to have one of the worst under five mortality rates, globally. Families are forced to choose between sending their girls for water or sending them to school, and they choose water first. This limits the prospects for their future, and the cycle of poverty in Mihingoni continues. Until now. “I didn’t want to make any assumptions about what the community needed, or what the solution should be,” Miller said. “The meeting was entirely spoken in KiGiriama, which allowed those most affected by the project to fully express themselves and their needs. We wanted to put the people’s needs at the center of all of our work.”

“I didn’t want to make any assumptions about what the community needed, or what the solution should be,” Miller said. “The meeting was entirely spoken in KiGiriama, which allowed those most affected by the project to fully express themselves and their needs. We wanted to put the people’s needs at the center of all of our work.”

Global Poverty and Practice student, Marissa Kaye Scott, travels to Malawi to support the program making big impacts in the “warm heart of Africa”. Click

Global Poverty and Practice student, Marissa Kaye Scott, travels to Malawi to support the program making big impacts in the “warm heart of Africa”. Click