November 2021

The October 2021 Innovation Chronicle is now available.

University of California, Berkeley

The October 2021 Innovation Chronicle is now available.

The August 2021 Innovation Chronicle is now available.

The June 2021 Innovation Chronicle is now available.

http://pub.lucidpress.com/cf2314aa-5977-4fb4-a6d9-94891b5a2e8e/?src=em

https://mailchi.mp/berkeley/development-impact-lab-turns-5-fighting-poverty-with-data-gpp-grads-xaoy5bck8a?e=3e274ed9da

https://mailchi.mp/berkeley/november-newsletter-1394221?e=[UNIQID]

Gamechangers. Engineers. Innovators. Researchers. Entrepreneurs. These are just a few of the words that describe the outstanding women of the Blum Center ecosystem. In honor of National Women’s History month, the Blum Center recognizes the outstanding work, achievements, and global impacts of these trailblazing women.

Laura Tyson, Board Chair, Blum Center for Developing Economies

Renowned economist, Laura Tyson, has spent a large portion of her career demonstrating how empowering women is morally right and economically smart, and that the economic and human-development costs associated with gender gaps are substantial. As co-author of Leave No One Behind, a “call-to-action” report of the UN Secretary-General’s High-Level Panel on Women’s Economic Empowerment, Tyson shows how gender equality and women’s economic empowerment are central to the vision of the Sustainable Development Goals, and cautions that progress has been too slow. In the UN report, Tyson identifies concrete actions the international community can take to expand women’s economic opportunities ranging from legal reform to changing business norms.

Erica Stone, Blum Center Founding Trustee, and President, American Himalayan Foundation

Erica Stone, Blum Center Founding Trustee, and President, American Himalayan Foundation

Over the course of her career, Erica Stone has worn many hats—fifth degree black belt, chef at Chez Panisse, and today, President of the American Himalayan Foundation. As the Foundation’s President, and particularly through the STOP Girl Trafficking initiative, Stone has had a profound impact on the lives of women and girls around the world. Each year, 20,000 girls from the poorest regions of Nepal are trafficked, which Stone attributes to three things: poverty, poverty, and poverty. By focusing on primary education, AHF lays a foundation that lifts girls out of poverty by giving them the skills, confidence, and respect they need to succeed. The STOP Girl Trafficking program started with 54 girls; today, 12,000 girls are safe in 500 schools across Nepal, on the path to a future full of hope. Learn more about STOP Girl Trafficking and the work of AHF.

Dr. Laura Stachel, Big Ideas Winner and Founder, We Care Solar

In 2008, with funding from Big Ideas@Berkeley, Dr. Laura Stachel worked with an interdisciplinary team to design a low-maintenance solar electric system for a Nigerian hospital with a high maternal mortality rate. When surrounding health centers requested solar electricity in their labor rooms, the compact, rugged We Care Solar Suitcase was born. Ten years later, more than 3,000 We Care Solar Suitcases have served 1.4 million mothers and babies in 27 countries. These user-friendly, mobile and nearly maintenance-free suitcases, which take a couple of hours to install, have proved an important innovation in the fight against maternal mortality worldwide. Stachel’s goal is to “Light Every Birth,” working with Ministries of Health to ensure that every health center has reliable clean energy for childbirth. Learn more about Dr. Stachel and the global impact of her work.

Alice Agogino, UC Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Blum Center Education Director

Alice Agogino, UC Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Blum Center Education Director

Professor Alice Agogino is a trailblazing mechanical engineer known for her work in bringing women and people of color into engineering, and her groundbreaking research into cutting-edge product design, intelligent learning and robotic systems, and sensor fusion, monitoring and diagnostic networks. As faculty Director at the Blum Center for Developing Economies, Alice has supported the growth of the development engineering program to include over 50% women, and helps build the interdisciplinary skills needed for students to create actionable and impactful research that is transferable from the lab to the field at scale. Watch Alice in action on development engineering and in sustainable products and services.

Dr. Sophi Martin, Blum Center Innovation Director, and

Dr. Sophi Martin, Blum Center Innovation Director, and

Dr. Rachel Dzombak, Blum Center Innovation Fellow

Many institutions recognize the need to transform their business practices to keep pace with a rapidly evolving technology landscape, but lack the tools needed to unlock the innovation potential of their organization. Dr. Sophi Martin and Dr. Rachel Dzombak are leaders within the Blum Center’s growing education portfolio that supports social enterprises, innovative individuals, and the larger entrepreneurship/innovation community on campus. Through their design- and lean startup-focused teaching and advising, Martin and Dzombak inspire students to take on the great challenge of transforming deep-seated societal problems. Learn more about Martin’s work, and Dzombak’s work.

Isha Ray, UC Berkeley Professor and Blum Affiliated Faculty

There are few people in the world who know more about the intersection of gender equality and toilets than UC Professor Isha Ray. When UN Women asked Ray to determine whether or not there was greater gender equity in access to sanitation on account of the Millennium Development Goals, Ray didn’t know, but she made it her mission to find out. With her research partners and seed-funding from the USAID Development Impact Lab, Ray launched a new research project (TriSan) to understand the connections among sanitation, gender equality and human dignity. Throughout the course of her research, Ray found that sanitation programs are still being designed without fully acknowledging the social and biological needs of low-income women and girls. She has been advocating for the water and sanitation rights of women and girls globally ever since. In this moving Tedx Talk, Ray breaks down the relationship between dignity, gender, and toilets.

On May 23rd, sixty-nine students representing thirty majors accepted certificates in the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) Minor from Professors Ananya Roy, Clare Talwalker, and Max Aufhammer, as well as Richard Blum, founder of the Blum Center for Developing Economies. Faculty and student speakers stressed the complexity of global challenges as well as the imperative of creatively combating those challenges each and every day.

“We can’t let the limitations we face bring us down or be intimidated by the magnitude of the work,” said student commencement speaker Sarah Edwards. “We can’t think things will never change. We can’t stop trying. Really, we can’t be stopped.”

The diversity of intended career paths in the GPP Class of 2013 is a testament to the program’s interdisciplinary nature. Students are bound for many destinations and types of work, from studying housing struggles in post-Katrina New Orleans, to working locally as an emergency medical technician while pursuing a graduate degree in humanitarian engineering design, to helping design a cultural center in a Samoan community nearly 5,000 miles away.

While many graduates intend to work locally, others in the class remain focused on global-scale interventions. Edwards and fellow student commencement speaker Nikki Brand will both be working overseas—Brand in Guatemala with the social entrepreneurship organization Community Enterprise Solutions, and Edwards as a Peace Corps Forestry and Agroforestry Extension Agent in Cameroon.

This diversity of student interests is unified through a shared commitment to community engagement. This year, three members of the GPP community were honored with prestigious Chancellor’s Awards for Public Service in recognition of their service to communities both local and global. The Chancellor’s 2013 Service Learning Leadership Award was given to Dr. Genevieve Negron-Gonzales, who taught the GPP capstone course as well as an enrichment course on educational justice and undocumented students. The 2013 Mather Good Citizen Award, which recognizes one graduating senior who has demonstrated a high standard of conduct and service to the campus, was awarded to Abhinaya Narayanan. In addition to her GPP studies and internships in the community, Narayanan served as Project Coordinator of Asha, a student-run organization providing education to underprivileged children, and as Student Director of Oakland Community Builders, connecting UC Berkeley students with internships at social justice organizations in the East Bay. Gardenia Casillas, another GPP student, received an Undergraduate Student Award for Civic Engagement. Casillas completed service work in Ecuador providing dental care to poor communities and plans to work in Ethiopia this summer, funded by a Harvard Fellowship in Public Health, before pursuing advanced degrees in medicine and public health.

As the GPP Class of 2013 disperses to all corners of the globe, the Blum Center is confident that this new generation of poverty action scholars is prepared to face the challenges, questions, and complexities of global development work. Dr. Negron-Gonzales bid farewell to her GPP students with an inspiring quote from Antonio Machado, reminding them: “Journeyer, there is no path. The path is made by walking.”

For more photos, visit the GPP Minor Graduation 2013 Facebook album.

By: Javier Kordi and Sean Burns

May 16, 2013 – Each summer, Global Poverty and Practice students travel to communities all over the world to engage in poverty alleviation work. By giving students on-the-ground exposure to the complex challenges of poverty action, these ‘practice experiences’ put classroom learning into new perspective. The Blum Center’s Student Fellowship program helps to fund a majority of these GPP students as they seek to collaborate with a variety of NGOs, government agencies, social movements, and businesses to turn their studies into tangible community work.

Guided by their own interests and questions, students are challenged to define a practice experience which advances their academic goals and aligns with their passions. For Zahra AbouKhalil, a third year student majoring in Public Health and fluent Arabic speaker, this means traveling to Lebanon in mid June to begin an internship with the Amel Association in Beirut—an organization working for the rights of Syrian refugees. Over 350,000 Syrian refugees have crossed into Lebanon since the start of the civil unrest in Syria. AbouKhalil’s practice experience will entail running health and sanitation workshops in the Amel’s refugee camps.

Each year, many GPP students view the practice experience as an opportunity to ‘give back’ to their home communities. Lorraine Mosqueda will travel to the island of Iloilo in the Philippines to complete her practice experience. Mosqueda, a third year majoring in Microbial Biology, will work alongside the Family Planning Organization of the Philippines to conduct community outreach and spread contraceptive awareness. A native of the island of Iloilo, she aspires to engage with her community on topics of women’s and family health that have been central to her studies at UC Berkeley.

International practice experiences such as AbouKhalil’s and Mosqueda’s have proven invaluable to student’s perspectives and professional goals. However, as GPP’s Professor Ananya Roy articulates in the foundational course of the Minor, students must also foster a “Politics of Locality”—that is, understand that poverty does not exist ‘out there’, but is instead a phenomenon with both local and international dynamics. Understanding this relationship between the local and international manifestations of poverty encourages students to not forgo the importance of poverty action in their own backyards. This year, the Blum Center witnessed a significant increase in students seeking local practices. Thirteen students will stay in California—ten of whom will be in Berkeley or Oakland—working on issues ranging from affordable housing and community health to food security and women’s economic rights.

Karem Herrera, a Public Health major, will complete her practice with Don’t Sell Bodies, an anti-human trafficking organization led by Cal grad Minh Dang that seeks to spread awareness through the telling of narratives. There are millions of individuals coerced into forced labor or sexual exploitation in the US, and the San Francisco Bay Area is considered by the FBI to be one most prominent locations for these illegal activities. Herrera’s practice experience will focus on assisting Don’t Sell Bodies in organizing conferences to increase survivor participation. The inclusion of survivors’ stories is central to the organization’s mission to empower vulnerable populations through education and awareness—a mission Herrera hopes to forward.

Local practices enable GPP students such as Hillary Acer to work on issues impacting UC Berkeley’s neighboring communities. Acer, a third year majoring in Integrative biology with a minor in Dance, will spend her summer in West Oakland interning with the well-known food justice organization City Slicker Farms. By assisting the organization with the expansion of their home and community gardens program, Acer will be working to increase access to healthy food in one of America’s largest ‘food deserts.’ This practice experience reflects her broader interests in community health and will give her exposure to food and nutrition challenges with an emphasis on social justice.

Capturing the essence of the practice experience, the Blum Center’s GPP Program Coordinator Chetan Chowdhry enthusiastically states: “The practice experience is a vital aspect of the GPP Minor because it allows students to directly engage with the political and ethical challenges that are inherent in efforts to address global poverty and inequality. As a result, it pushes them to think critically about what meaningful global practice entails.”

By: Javier Kordi

In early April, eighteen UC Berkeley students attended the Clinton Global Initiative University (CGI-U) conference in St. Louis, Missouri, eager to make progress on their “commitments to action”—student-led projects which aim to tackle the most pressing challenges facing humanity. With $500,000 available for investment in student projects—in addition to funds and support from the institutions in the University Network—and an all-star line-up of keynote speakers, this year’s event provided an unprecedented atmosphere of collaboration, innovation, and networking.

Ngan Pham, a student in the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) Minor, described CGI-U as refreshing because it brought together a “group of ambitious and humble individuals” all aspiring to create a positive change. Pham’s project, “ServeFund,” prepares low-income students to be competitive and financially eligible for internships and public service opportunities—experiences that employers value highly in today’s job market. Because CGI-U brings together prominent public figures and private sector leaders, student attendees are often able to network with their idols. Pham recalls one serendipitous morning at CGI-U when she met and exchanged contact information with Professor Mohammad Yunus, an economist and Nobel Peace Prize recipient specializing in microfinance.

CGI-U supports a diverse spectrum of student commitments, from social service projects to science-driven solutions to local and global challenges. The conference gave Connor Galleher and Matt Pavlovich an opportunity to unveil their first venture in global poverty alleviation. Utilizing their knowledge of plasma physics and chemical engineering, the duo constructed a device that generates plasma as an affordable and low-input sanitation agent for water and surfaces. Requiring only electricity and air, their device has immense potential to curb infection and disease when used in developing countries. Galleher and Pavlovich were one of two teams to present on-stage in the “Solving the Global Sanitation Crisis” session.

Pavlovich emphasized how easily it was to build partnerships with other attendees. The eerie glow of their prototype on display attracted many at CGI-U, including Stephen Colbert, who described the event as “a science fair for noble causes.” Even CGI-U host President Bill Clinton casually walked over to their booth, and—after listening to their pitch—picked up their business cards and mentioned the possibility of providing solar panels for their power needs.

Beyond networking, Galleher and Pavlovich’s exposure in the CGI-U space encouraged the team to rethink the way they presented and marketed their idea. Galleher recalled that “people were in pain when reading our [poster]” because few attendees were familiar with the language of plasma physics. The project team was compelled to “recalibrate [their] message” in order to make it more accessible. They now have a website and a pending project title—“PlasMachine”—that they hope will make the seemingly esoteric topic more understandable and accessible for the general population.

Karem Herrera, also a GPP student, described the three day CGI-U conference as “empowering” because it spoke to all aspects of the poverty challenge—including the inevitable failures and obstacles that aspiring change-makers encounter—and provided opportunities for collaboration. Herrera’s commitment is to organize a youth empowerment program in Aguascalientes, Mexico. Working with a team of approximately fifteen UC Berkeley students through MEND (an on-campus organization), her program will extend educational resources to economically disadvantaged youths in Aguascalientes. During the event, she met the directors of a similar project, Union De Jovenes Por Mexico (Union of Youth for Mexico), and may work closely with the group in the near-future.

Sean Burns, Director of Student Programs at the Blum Center, feels the conference offered an important experience for UC Berkeley students on a number of levels. “Students were able to analyze the vision and strategy of their projects,” he remarked. “They were able to meet and converse with dozens of experienced leaders in social change and innovation, and return to campus with a bolstered sense of enthusiasm and confidence for carrying forth their project commitments.” Burns, who serves as the UC Berkeley campus representative in the inaugural year of the CGI-U University Network, looks forward to continuing to work with these students as they seek to fulfill their commitments to action.

Read more about the Blum Center’s role in the CGI-U University Network.

April 17, 2013 – My path to the Truman Scholarship began to take shape generations ago, when my great grandmother frequented UC Berkeley’s hallowed grounds while pursuing degrees in Spanish and history. My grandmother, currently 96 years old and still reflecting fondly on her time at Cal, similarly began her studies here only to leave to take a job at Lawrence Berkeley Lab as an engineering designer. My mom also began to pursue a degree here before decamping to take a job in the city. I was born in San Francisco and grew up hearing about UC Berkeley, but it always seemed like a distant institution that belonged to my ancestors. As a graduating high school senior I was certain that I wanted to study environmental science and engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo to begin a career in Californian river restoration work.

However, my path radically shifted when I enrolled in an Appropriate Technology course that included fieldwork in rural Guatemala. Bearing witness to abject destitution profoundly refocused my perspective, and I began to understand the problem of poverty for the billions of people living without safe water, education, and health care. Learning how to negotiate the complex divides between poverty and wealth helped me develop my own solidarity in the context of inequality, and this experience learning to bridge cultural difference and seek transnational similarities inspired me to apply to transfer to UC Berkeley to enroll in the Global Poverty and Practice Minor.

Once at Berkeley, I declared majors in Society and Environment (B.Sc.) and International Development and Economics (B.A.) through the interdisciplinary field studies program. For my GPP practice experience, I sought to unite these fields by working on rural water projects with the Foundation for Sustainable Development and Water for People in Cochabamba, Bolivia from May to August 2012. Many of my days consisted of visiting communities without connections to the municipal water supply and discussing the role of water cooperatives in improving access. Through this work, I found a significant component missing from the work of the organizations: addressing the asymmetrical impacts of a lack of water on women and girls. I am now leading the expansion of gender sensitive water programs in twelve rural schools in Bolivia this summer, and am a finalist for the Human Rights category of the BigIdeas@Berkeley competition to support these efforts.

While at Cal, I have participated in two Undergraduate Research Apprenticeship Program (URAP) projects with Blum Center associated faculty and am currently working with Professor Isha Ray to generate a literature review on the current state of water treatment models in Latin America. My first honors thesis, a formative component of my research engagement at Cal, analyzed the formation of current conditions of water access, control, and management in Cochabamba, Bolivia. The municipal government in Cochabamba theoretically incorporated civic participation as an element of their planning system through the conduits of varying levels of administration. However, a 2004 report by the United Nations RISD found clear evidence that elements of class-based discrimination and resulting inequalities in access to water existed in the residential peri-urban spaces of Cochabamba, with such inter-urban spaces becoming places where the population is an indicator of processes of social differentiation (UNRISD 2004). The insurgent urbanization of Cochabamba resulted in the rise of numerous squatter settlements, zones of informal housing, and distinctively “peri-urban” regions on the outskirts of the city. Asymmetrical political power distribution is most obviously manifested in the noticeable absence of municipal services that are provided to the wealthier districts of the city, including water and sanitation. In this way, I came to understand water as not just an environmental, economic, social, or cultural resource, but also the site of considerable politicized inequity. These diverse research experiences that often cross into advocacy have collectively reinforced my belief in the importance of working across disciplines to achieve the goals of reducing poverty, improving global health, and increasing equality in water and environmental resource distribution.

Over the past two years, I revitalized the Water IdeaLab, co-founded a DeCal on water and international human rights, and collaborated with faculty to create an undergraduate curriculum to improve water related student opportunities. I also lead the Nuestra Agua student group, and alongside fellow students introduced a social justice and human rights perspective to the organization which was previously narrowly focused on the role of UV technology and health outcomes for reducing water borne illness in rural Mexican communities. The program in Chiapas will be the summer practice experience for three GPP students to contribute to safe water programs.

While I am thrilled that my efforts thus far have helped engage students in water issues on campus, in the community, and around the world, there are still miles to go. The Truman and Udall scholarships, along with the Berkeley Law Human Rights Fellowship, are honors that I take very seriously as long-term investments to foster my commitment to water, social justice, and human rights work. My roots at Berkeley, beginning with my great grandmother, instilled in me a deep sense of history and appreciation for the educational experience here. I am still awed by the sheer physical beauty of the architecture, inspired by the intellect of my peers, and humbled by the opportunities I have as a student at Cal.

After graduating from Cal and working in Washington, DC with the State Department through the Truman Scholars Institute, I intend to pursue dual masters degrees in Water Science, Policy, and Management (M.Sc.) and International Development (M.A.) which will enable me to contribute to the design of meaningful policies that will shape the future role of the United States in water and the environment. In the future, I hope to work with the State Department’s new US Water Partnership to define its direction as a leader in US foreign policy related to issues of environmental sustainability and water security. My vision is to address inequitable water consumption practice while targeting the improvement of strong civil societies able to hold their government representatives accountable to the social, economic, and cultural demands of water. Through designing policies that empower governments to fulfill their obligation to provide affordable and accessible safe water to their people, I hope to make access to and control of water resources a more inclusive, transparent, and equitable process.

Some advice I would offer students looking for ways to get involved in poverty action are to utilize campus resources like the Blum Center, the Scholarship Connection, the Center for Effective Global Action, and Cal Corps. The mentorship and support I have received from the faculty and staff at the Blum Center have been critical to my activism, research, and advocacy for poverty and water issues. The lasting friends I have made through the Global Poverty and Practice minor – the other peer advisors, my classmates, and my Bolivian partners – inspire me every day with their creative brilliance, thoughtful innovations, and deep compassion. The Blum Center has effectively created a space to allow for a new vein of student driven and institution supported work that facilitates the millennial generation’s mission to theoretically and practically engage with the challenges of global poverty and inequality. Effective poverty action requires informed actors, and the millennials at Berkeley are capable of critically engaging to end the inequality that drives pressing economic, environmental, and social problems. Go Bears.

Visit Peters’ blog for more about her research and travels.

Read more about Peters in ‘Fourth-generation Berkeley student lands prize for water work’ via UC Berkeley NewsCenter.

Author:

Brittany Schell

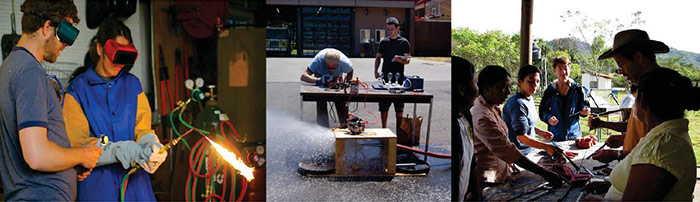

Professor Addy also teaches a course at UC Berkeley, Design for Sustainable Communities. The class gives students hands-on experience in the design and implementation of projects meant to improve the sustainability of communities in developing countries.

The students work in teams throughout the semester on practical projects, with guidance from professor Addy and other experts. The class, a mix of graduate and undergraduate students from various majors at Berkeley, meets twice a week to discuss their own projects as well as explore the methods of successful innovators.

“One of the most pressing challenges of the new century is to harness the extraordinary force of technological innovation…and make

its benefits accessible and meaningful for all humanity,” professor Addy said to begin class, quoting former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.

Cost effective, creative solutions to problems like unemployment and the lack of water and electricity in villages—like professor Addy’s ECAR water initiative—provide a new area of opportunities for businesses and social entrepreneurs. It’s innovation for the 90 percent, she told her students.

Author:

Javier Kordi

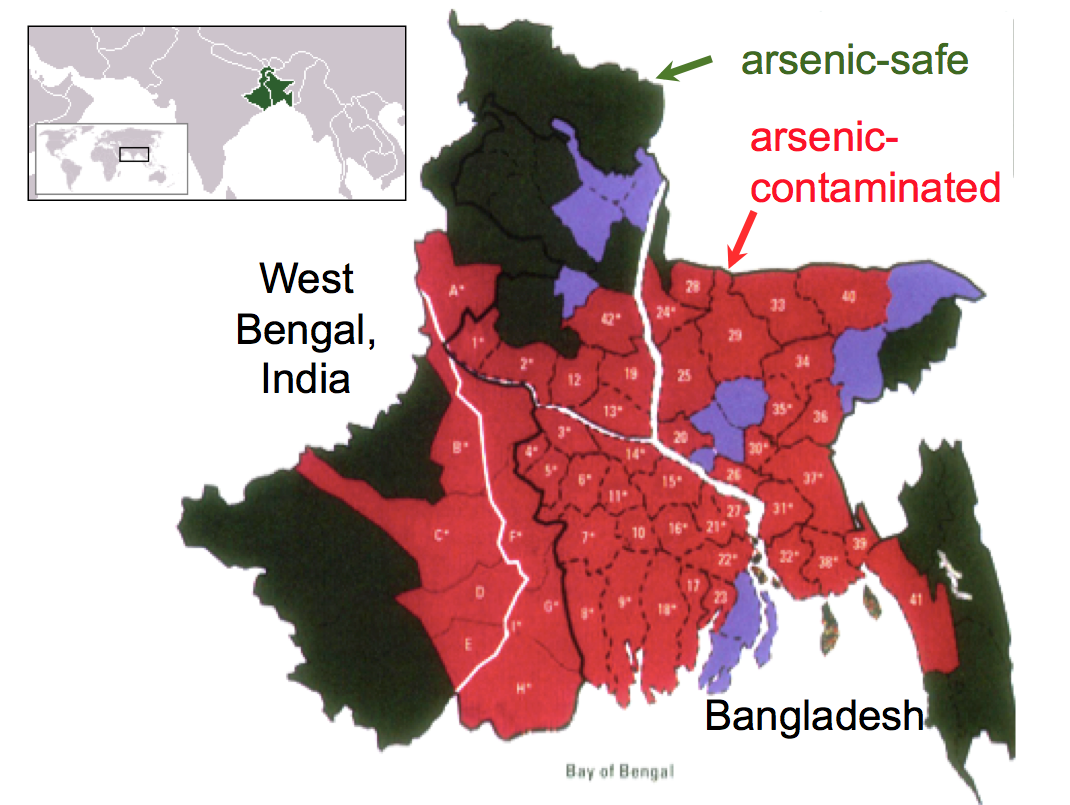

Abandoned arsenic water filters litter the village of Amirabad, India like archaic ruins. For years, the community has seen foreigners come and go, bringing the promise of clean water and leaving behind hollow philanthropic gestures. Arsenic- contaminated ground waters have created the largest mass poisoning in human history. In Bangladesh alone, 40 million people are exposed to arsenic through their tube wells. From Latin America to Asia, arsenic-laden water has plagued the lives of millions.

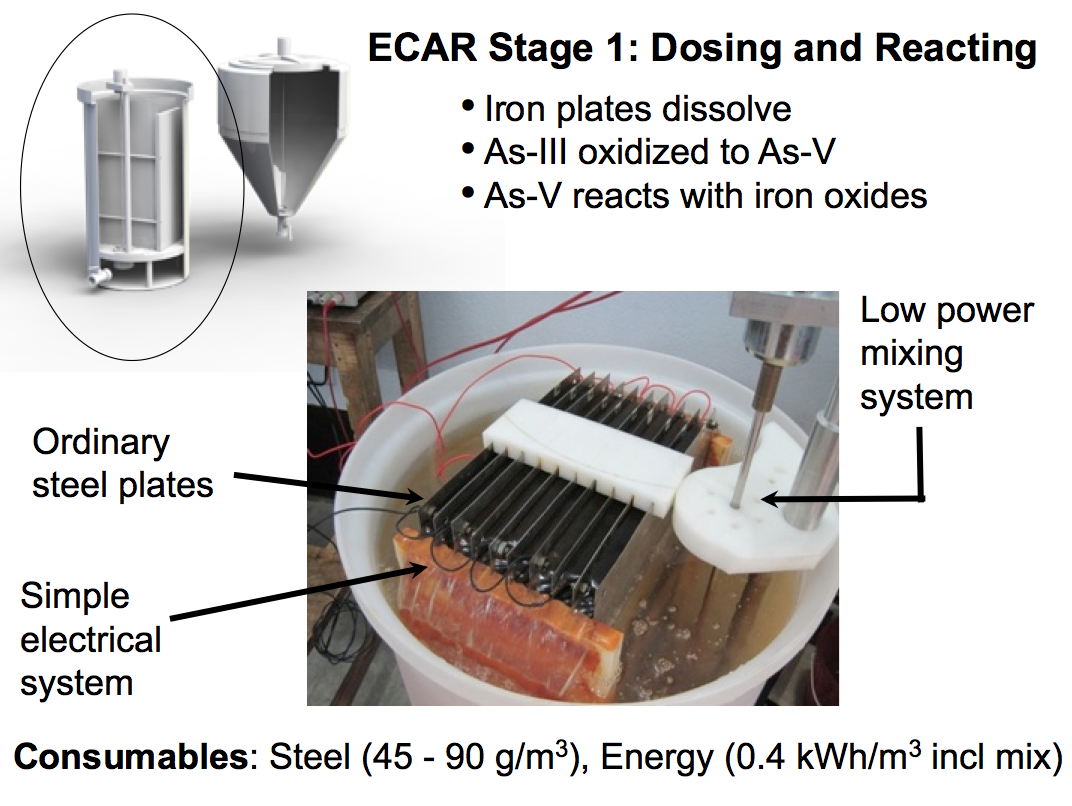

Working in conjunction with the Blum Center for Developing Economies and the Lawrence Berkeley National Labs, professor Susan Addy and her team of scientists have brought something new to the water table: a sustainable model for water purity— the Electrochemical Arsenic Remediation project (ECAR).

ECAR differs from its predecessors in its mode of arsenic extraction. The elusive arsenic particles cannot be removed with traditional filtration— they will not settle or get retained. ECAR works by literally grabbing these particles and dragging them to the bottom of a water basin, separating them from the clean H2O. It is a simple procedure.

First, a steel plate is placed into a tub of water. Then an electrical current

is passed through the steel, creating millions of rust particles. As the rust expands, it electrochemically binds

to arsenic. The rust-bonded arsenic settles to the bottom of the basin and the final step—adding Alum, a water coagulant—allows the amalgamation and separation of the poison. The 100 liter prototype produced clean water that was indistinguishable from bottled water, using only as much energy as a CFL light bulb.

But even the most brilliant of technologies cannot succeed if they are not embraced and maintained by the local community. “The technology is maybe 20 percent of the problem,” professor Addy said. “The social situation, making it work sustainably, is maybe 80 percent of the problem.” Often times, water projects fail because they are a one-time gift from a donor. Working with financial institutions, a social marketing firm and local governments, the ECAR project will make the delivery of clean water part of the community’s livelihood. The product of ECAR (clean water) will become a good, to be sold and profited from in an open market, thus creating an economic incentive for continued production.

Professor Addy explained the plan for this year: “We’ve got two pilot projects planned this year that will serve water to about 2,500 students, maybe one to two liters per day, operating for several months.” As children learn about water safety in their classrooms, the neighboring water plant will transform the school into a community center—a nexus for health and education. Ultimately, the plant will provide jobs for the local people. While providing free water to children, the excess that is created can be sold to the community. ECAR aims to become a self-sustaining water plant, both economically and technologically. Because the government has an interest in increasing student enrollment, professor Addy believes there is potential for partnering with India’s Ministry of Education to further subsidize the project.

At the end of February, two scientists, Christopher Orr and Sivarama Satyam, will depart from Berkeley to spend six months in India testing out the new 500 liter prototype. After working with a manufacturer in Mumbai, the prototype will be shipped to Jodhpur University in Calcutta for a few months of testing. If all goes well, this prototype will be moved to the school in Amirabad, India, where it will provide six months of free water to local school children. According to Sivarama, local governments and communities are eager to adopt the technology, particularly after the success of the initial model. With continued successes, the full implementation of ECAR and the cleansing of the water table will soon be a reality.

Author:

Javier Kordi

Upon entering Berkeley’s all-you-can- eat dining halls, students undergo a strange biological transformation: their eyes seem to swell, far exceeding the size of their stomachs. Seven servings later, a tray full of half eaten entrées stares back at their defeated gazes before getting disposed of in the garbage. This propensity to waste is not limited to university dining halls. Every day, 260 million pounds of food are wasted while 50 million Americans go hungry. Witnessing this incongruity first hand, Global Poverty and Practice students Komal Ahmad, majoring in International Health and Development, and Jacquelyn Hoffman, majoring in Gender and Women’s studies, created BareAbundance—an organization that addresses the inequitable food distribution that causes millions of Americans to suffer every day.

When food is neither consumed nor sold, or is nearing its expiration date, the organization sweeps in to intervene before it is tossed into a landfill. Receiving excess healthy food from a wide network of sources, BareAbundance redistributes this excess to people in need. Last year, BareAbundance signed a contract with Cal Dining, securing the excess foods from four dining halls and 10 on-campus cafes and restaurants. Currently, this food is being delivered to an afterschool program at New Highland School in East Oakland, where 70 percent of students are on free or reduced lunch.

Komal, one of the founders of BareAbundance, explains that the after-school program is about more than providing food; it’s also about food education. For a community lacking access to farmers’ markets, the nutritional model of the food pyramid is sometimes hard to meet. In addition to providing much-needed sustenance, the after-school program teaches “food driven values through an experiential method where [the students] consume and cook the food.”

Take one of the program’s three-day examples: children were first given donuts and asked to write about how they felt in their journals. Initially abounding with energy, the children reported stomachaches and lethargic feelings a few hours later. A similar feeling was reported the next day when the kids ate pieces of cake. On the final day, the children were given a luscious piece of fruit. They wrote in their journals that, not only did it taste good, but it also provided sustained energy without a sugar crash. This technique trains children to recognize the importance of a healthy diet through direct engagement.

Last year, BareAbundance was selected as a winner of Big Ideas @ Berkeley, a campus-wide innovation competition managed by the Blum Center. A recipient of the Social Justice and Community Engagement award, the organization received funding for transportation, food storage, website creation and publicity, allowing it to grow dramatically. Komal humbly described how the Big Ideas @ Berkeley grant “legitimized our organization…our idea.” It compelled the founders to make their model of food redistribution a reality: as Komal said, it was “both a pat on the back and a kick in the ass.” In the future, Komal hopes to establish a nation- wide food recovery network to save and distribute excess food from college campuses around the country.

Author:

Brittany Schell

February 20th marked the annual World Day of Social Justice. “Social justice is an underlying principle for peaceful and prosperous coexistence within and among nations,” states the website of the United Nations. “We advance social justice when we remove barriers that people face because of gender, age, race, ethnicity, religion, culture or disability.”

In 2007, the UN General Assembly declared February 20th of each year the “World Day of Social Justice,” to recognize groups around the world working to fight poverty and promote gender equality, access to health care and other initiatives that advance development and human dignity.

Here at the Blum Center, our students and faculty work actively toward these goals. Each year, we offer fellowships to students studying in the Global Poverty and Practices minor at UC Berkeley to help fund their summer fieldwork experiences.

Fieldwork has ranged from supporting tenants’ rights in New York City to providing access to clean water in India; improving child nutrition in Guatemala and addressing poverty in Vietnam; working with opium addicts in Afghanistan and HIV/ AIDS prevention work in Ghana; and even building community bread ovens in Tanzania. Our students have helped advance the foundation of social justice through hands-on work, making concrete differences in communities across the world.

Last summer, 40 students received fellowships from the Blum Center.

Author:

Luis Flores

It’s a practical course,” explained Royce Chang about professor Tara Graham’s Field Reporting in the Digital Age: Using Media Tools for Social Justice. “I don’t think we get enough of that here at Berkeley.”

Professor Graham’s course trains students in Berkeley’s Global Poverty and Practice minor to use the Internet and social media as tools for global engagement. The course is an all-in-one tool kit for global awareness.

Last year, students received training in everything from film, photography and creative writing to web design. “The course was valuable because it trains you to look for things and to look for the best and most ethical way to go about acquiring material,” remarked Royce. Professor Graham is teaching the class again this semester.

Royce, a history major concentrating on ancient Greece and Rome, is currently working on developing media content for One World Futbol at Berkeley, an NGO that is working to spread global and community awareness among local K-8 students through sports. He continues to believe that no matter the initiative, the spread of awareness is a vital part of enacting positive change. To this goal, online media is a valuable tool.

Ryan Silsbee, another of professor Graham’s students last year, has since graduated and is completing a four-month organic agriculture apprenticeship with Real Time Farms in Hawaii. The importance of the media skills learned in professor Graham’s class are obvious by looking at his website: a clean site with vivid photographs, concise, creatively written updates and interactive maps and guides. His site allows readers to engage with his mission of promoting healthy and organic agriculture. “Spreading information and just getting people interested in where their food comes from and how it is grown is the first step,” Ryan said.

The theoretical courses in the GPP minor set Ryan on a path to change American agriculture, and Professor Graham’s course gave him the tools tostart making those changes. “I want people to step out of their busy lives, take a look at agriculture in the United States and decide for themselves if they think something should be changed,” he explained.

Many of professor Graham’s students, like Danika Kehlet, were first able

to put these skills to use during their summer practice initiatives. Armed with a small flipcam, Danika set out to chronicle her work promoting female development in Quito, Ecuador. Her lively blog illustrates her experience through the use of videos, photo collages and engaging blog entries.

This semester, Professor Graham is training a new group of GPP studentsin a similar course: Using Media Tools for Global Poverty Action. Practical courses like these are training the next generation of tech-savvy global citizens. Exposure to the development possibilities of social media is empowering and inspiring students.

“It is very inspiring to know that something I create, write, photograph, film, or document can change the way people view their world,” Ryan said. “If enough people see it, you can change society.”

Author:

Javier Kordi

On October 10th, the Blum Center received national attention: Rajiv Shah, the administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) ventured across the country to meet with the UC Berkeley community. The Blum Center was honored to host Director Shah, as he spent the day engaging with students, meeting faculty and board members, and learning about the latest initiatives in poverty alleviation.

Dr. Shah’s visit marked the first in what will be a continued, symbiotic partnership between the federal agency and the Blum Center. Towards the end of his visit, he delivered a keynote address to an overflowing audience of students, professors, and community members. Dr. Shah praised the center’s focus on “deep analysis and broad engagement… that not only generates new ideas, but also tests and applies real-world solutions.” He noted the uniqueness of the Blum Center’s approach, which combines topdown efforts with empowerment and sustainability from the ground-up.

In his speech, Dr. Shah noted his interest in solutions such as the WE CARE Solar Suitcase and the Cell Scope. With their respective abilities to curb infant mortality and facilitate early disease diagnosis in rural areas, these initiatives are a sampling of the promise of university-level development to help the poor. Dr. Shah explained that the process of interdisciplinary collaboration that birthed these projects now serves as “the model for a network of development laboratories [USAID] is forming across the country.”

The next era in poverty alleviation will be defined by an open-source approach to development that breaks down barriers limiting the availability of the latest innovations. The opensource paradigm holds the key to implementing sustainable and replicable real-world solutions. An example Dr. Shah mentioned was a mobile phone equipped with geographic information system capabilities. Made readily available to the hands of vulnerable populations, this device would allow atrocity victims to record critical information (such as time, place, and photographs) to be used as substantive evidence in international courts.

The next era in poverty alleviation will be defined by an open-source approach to development that breaks down barriers limiting the availability of the latest innovations. The opensource paradigm holds the key to implementing sustainable and replicable real-world solutions. An example Dr. Shah mentioned was a mobile phone equipped with geographic information system capabilities. Made readily available to the hands of vulnerable populations, this device would allow atrocity victims to record critical information (such as time, place, and photographs) to be used as substantive evidence in international courts.

USAID understands that even the most brilliant technologies are mere tools— without a solid implementation platform, their impacts are limited. For its projects to succeed, an organization must have a fluid ideology that can operate within the varying landscapes and climates of development. This requires a lively discourse on the methods and approaches to development. On university campuses, the conversation is ever-growing, and USAID wants to join in. According to Dr. Shah, USAID aims to spark a dialogue with the millennial generation of activists and scholars emerging from places like UC Berkeley. In pursuit of this goal, USAID has created an online-space called USAID Fall Semester which seeks to invite students to converse, critique, and collaborate with the organization.

Dr. Shah ended his speech with an inspirational call to action— stating that extreme poverty could be reduced by 90% if efforts were accelerated. He then opened the floor to questions, and a lively conversation ensued. It was a day to be remembered for the students and faculty at UC Berkeley. As the Blum Center’s model is replicated and leveraged, with new partnerships across people, institutions, and ideas— a new chapter in the fight against poverty begins.

Author:

Luis Flores

More than 450 undergraduate and graduate students submitted proposals to one of the Big Ideas@Berkeley’s nine contest categories – representing the largest contest to date. With $300,000 in expected awards, winning proposals will receive the critical support and funding that could spread their idea and address social and global challenges. To the benefit of big ideas everywhere, the opportunity to cultivate innovative plans into real-world projects could soon become available to university students around the country.

This year, UC Berkeley students interested in the Big Ideas@Berkeley contest were presented with two new global challenges: (1) develop a proposal that will preserve of promote the protection of individual’s essential rights and (2) design an innovative solution that will safeguard the health of expectant mothers and young children. Kicking off a dynamic partnership, Big Ideas@Berkeley and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) collaborated to open two new contest categories. The new “Maternal & Children Health” and “Promoting Human Rights” contest categories were inspired by USAID’s “Savings Lives at Birth” and “Tech Challenge for Atrocity Prevention” challenges. USAID’s initiatives foster a similar level of creativity by allowing groups of all sizes and from all backgrounds to contribute to addressing these pressing issues. Big Ideas has taken problems important to USAID and challenged UC Berkeley students to address them.

This year, UC Berkeley students interested in the Big Ideas@Berkeley contest were presented with two new global challenges: (1) develop a proposal that will preserve of promote the protection of individual’s essential rights and (2) design an innovative solution that will safeguard the health of expectant mothers and young children. Kicking off a dynamic partnership, Big Ideas@Berkeley and U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) collaborated to open two new contest categories. The new “Maternal & Children Health” and “Promoting Human Rights” contest categories were inspired by USAID’s “Savings Lives at Birth” and “Tech Challenge for Atrocity Prevention” challenges. USAID’s initiatives foster a similar level of creativity by allowing groups of all sizes and from all backgrounds to contribute to addressing these pressing issues. Big Ideas has taken problems important to USAID and challenged UC Berkeley students to address them.

In addition to expanding the number of categories in the contest, the Big Ideas team is working to expand the contest to other universities. We’re currently working to develop “Big Ideas in a Box,” explained Jessica Ernandes, a graduate student assistant for the Big Ideas contest. “Our goal is to share the framework and process with other universities so they have the tools that have proven useful for us.”

While still at an early stage of development, this collection of documents will detail everything needed to manage a university-based innovation competition. The idea to replicate this contest was prompted by the recently announced Higher Education Solutions Network (HESN). In partnership with USAID, UC Berkeley is working with six other universities to share and develop technologies and practices needed to collaboratively address global problems. A key piece of this effort is focused on challenging and preparing the next generation of innovators and entrepreneurs.

That’s where Big Ideas@Berkeley comes in. The contest succeeds because it does not simply grant prize money. The contest application process itself is an ecosystem for nurturing social innovation. From the pre-proposal phase, Big Ideas provides guidance, mentorship, and support to applicants, allowing students to grow their ideas during the 8-month long contest. This key feature should be central to any Big Ideas contest replica. “To foster student innovation, you have to know where students need support and what they’d like to get out of a program like Big Ideas,” explained Ernandes. “Listening to them is a necessary first step to ensure that the Big Ideas competition continues to be relevant and impactful as it moves to other campuses.”

The growing focus on university students is encouraging to Alexa Koenig, interim executive director of UC Berkeley’s Human Rights Center. A judge for the “Promoting Human Rights” contest category, Koenig believes young people are the best problem solvers. “Students are constantly being exposed to new ideas, whether from their professors, events on and off campus, or their peers, which can contribute significantly to creativity,” she explained.

“Big Ideas in a Box” is only one of many collaborative projects that will come out of the HESN, but it is a significant one. The Big Ideas competition will provide a pipeline of essential interdisciplinary and intergenerational perspectives on how to develop solutions to address social challenges.

It may not be long until students can apply to Big Ideas at universities throughout the country and the world. “In many ways, I think our model can be replicated because it is, at its heart, really simple,” explained Ernandes, “we support and allow students to do what they are great at being passionate, smart, and creative.”

Author:

Christina Gossmann

Giving a man a fish is good. Teaching a man how to fish is better. Yet, fishing is useless without a river. According to Dr. Kurt Kornbluth, the history of development is filled with examples of good intentions with sufficient capital but insufficient preparatory research and little follow-up to devise the most sustainable solutions. To counter such well intentioned by uninformed development work, Kornbluth founded the D-Lab at the University of California, Davis, with support from the Blum Center for Developing Economies.

D-Lab stands for Development through Dialogue, Design and Dissemination and aims to improve living standards of low-income households by creating and implementing appropriate, sustainable low-cost technologies. Inventor and educator Amy Smith launched the first D-Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). During the developmental stages of the initiative in 2005 Kornbluth, then a PhD student in Mechanical Engineering at UC Davis, assisted her Smith during the developmental stages of the initiative in 2005. Since then, MIT’s program has successfully grown to offer sixteen different courses, exploring development, design and social entrepreneurship. Following the success of MIT’s D-Lab, Kornbluth wanted to bring the program to UC Davis; after finishing completed his graduate work and then embarked upon a mission to establish his own D-Lab at UC Davis.

Focusing on issues such as off-grid power, post harvest crop preservation, irrigation, and renewable energy, the D-Lab at UC Davis offers two hands-on courses for graduate and undergraduate students at the intersection of energy and international development. The first course gives an overview of development work around energy, while the second provides students with a platform to design for the energy market. As part of the class, D-Lab students are directly coupled with clients who face a specific problem. They spend ten to twenty weeks working with these clients in different parts of the world—from Zambia and Nigeria to Bangladesh, India and Nicaragua—to offer concrete solutions.

“Students at the D-Lab always work with real problems and real people,” Kornbluth explained in an interview. The students’ designs don’t remain in academia but directly impact people in the field. Clients get answers—students gain real-life experience.

Throughout the process— rainstorming and narrowing ideas and transforming feasible solutions into real pilot projects—sustainability is the number one priority. All projects must take into account what Kornbluth calls the “four lenses of sustainability:” environmental, economic, social, and technical. In two project-review sessions per quarter, practitioners, academics and peers provide students constructive, often hard-edged feedback. Most D- lab students are graduate students from different fields and disciplines, including engineering, economics, international development. This diversity allows students to learn from each other as much as from the process of designing a sustainable energy solution.

While it is crucial to carve out a concrete and substantial project within the time period of the course, some of the more successful solutions have stayed with students beyond their D-Lab experience. One D-Lab graduate used the “SMART light” prototype he had developed in D-Lab as part of his portfolio when applying to a job after graduation. Another student recently received $40,000 from “Start up Chile,” a government- sponsored program designed to draw start-up technology companies to the country, to further his efforts in bringing safe water to Chile.

Despite the successes, Kornbluth humbly admits that, as in any field, not all projects work out great. “In D-lab Maybe 25% are a total flop, 25% will be mediocre and about 50% are really good,” Kornbluth said.

But those innovators who are successful create real impact—especially when they get together. The UC Davis D-Lab is part of the International Development Design Summit (IDDS) network. Once a year, 60 to 80 practitioners from around the world assemble for a different kind of academic conference. Under the banner of co-creation, students, teachers, professors, economists, engineers, mechanics, doctors, farmers and community organizers present technology and enterprise prototypes instead of academic papers. Meeting in Kumasi, Ghana, and Sao Paulo, Brazil, in 2012, IDDS leaders intend to launch additional locally organized summits in 2013. The goal is to turn these meetings into regular, university-based innovation hubs to exchange technology ideas.

Feasible, applicable and replicable solutions reach far, but networks are also of great importance. Since the beginning, UC Davis and MIT have been collaborating in developing the D-Lab curriculum, and they are looking for other universities to adopt the D-Lab model. “D-Lab is really about new technologies, and working with them in context. But it’s also about curriculum and it’s about networks,” Kornbluth explained.

In a university consortium with MIT, the D-Lab has just become part of a greater, brand-new network: the USAID Higher Education Solutions Network that was launched on November 9th 2012. In this 5-year partnership with seven top U.S. and foreign universities (among them, UC Berkeley), this initiative will harness the best ideas to fight poverty through development laboratories similar to the D-Lab. If this new generation of development professionals learns how to research, design, test and scale up effective development technologies, there is reason to hope that there will be no more fishing without water in international development.

Curious about the Higher Education Solutions Network and the new partnership between USAID and UC Berkeley? Read “Big Ideas In a Box” by Luis Flores for more information.

Author:

Kate Lyons

Gram Power, a company incorporated in 2012 by campus graduates Yashraj Khaitan and Jacob Dickinson, is expanding its reach with help from the Blum Center and United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The company’s mission is to provide affordable electricity to thousands of individuals who have restricted access to power in rural India.

Areas with little access electricity rely on kerosene — a dangerous and unhealthy power source. Gram Power offers communities “pay as you go” electricity. It is a system of micro-payments based on the successful model of prepaid cellular phones connections by Indian telecommunications companies. This “pay as you go” system is designed for low-income workers who earn a daily wage, providing them with access to green energy without a large up-front investment.

Yashraj Khaitan graduated with a degree in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) from UC Berkley in 2011. During his time as an ndergraduate, Khaitan was involved with solar cell research at Lawrence NationalLabs and helped found the UC Berkeley chapter of Engineers without Borders.

Jacob Dickinson, also a graduate of the EECS department, is the head of Gram Power’s technical development. As an undergraduate, Dickinson led the UC Berkeley’s Solar Car Team’s electrical division.

The two first met at a training session for UC Berkeley’s Solar Car team in early 2010, where they discussed Khaitan’s experience participating in grassroots projects with villagers in rural Rajasthan; a large desert state located West of New Delhi. It was from this experience that Khaitan’s idea to develop a sustainable electricity project arose. Upon hearing the pitch, Dickinson’s interests were enlivened, and he became immediately involved with the project, developing technology and seeking product validation.

“I first understood their needs, evaluated current solutions, decided on a price point that would be affordable and then started concept design,” Khaitan said.

Gram Power’s smart stackable battery, called an MPower, is a portable storage system made up of a battery and “smart power” conditioning circuitry. Small and lightweight, MPower fulfills Gram Power’s two main objectives – creating a power source that is flexible (can be used for powering more than lighting) and energy efficient. By reducing power consumption with efficient green technology, Gram Power enhances the individual’s investment and contributes to a cleaner environment.

The MPowers can be charged from a conventional power grid, a micro grid, solar panels or a bicycle dynamo. A fully charged MPower can charge a cell phone and provide power for lamps and fans; a fully charged stacked battery can power a television or computer. Gram Power believes its energy solution will impact communities’ light and communication capability, resulting in more education, work productivity and higher earning potential. The power is renewable and clean, providing environmental and health benefits, while Gram Power’s business model encourages local economic growth by employing individuals from each community as Area Sales Managers.

“Our main concern was affordability and utility. We wanted to design something that provided high utility at the right price,” Khaitan said.

Development and funding of the project began at UC Berkeley. After discussing his ideas with professor of Computer Science Dr. Eric Brewer in 2010, Khaitan began working with Dr. Brewer and the UC Berkeley research group TIER (Technology and Infrastructure for Emerging Regions). TIER designs and deploys new technology that helps addresses a particular region’s environmental, political and/or economic concerns with innovative hardware and software infrastructure.

In 2011, Khaitan and Dickinson decided to enter Gram Power into Big Ideas @ Berkeley, an annual, campuswide prize competition that provides funding, support and encouragement to interdisciplinary teams with innovative ideas. Dr. Arthur H. Rosenfeld, former Professor Emeritus of Physics at UC Berkeley and Chairman of the California Energy Commission judged the competition, and selected Gram Power for First Place in the Energy Efficient Technologies category. Gram Power was provided seed funding from the Arthur H. Rosenfeld Fund for Global Sustainable Development and the UC Berkeley Blum Center for Developing Economies.

“Apart from providing significant financial support to deploy our systems in the field in India, Big Ideas helped us think through our business model thoroughly,” Khaitan said. “The feedback and advice repeatedly made us aware that technology is not the most important thing – creating affordable and sustainable access is.”

With the support and advice of the Blum Center and the Arthur H. Rosenfeld Fund, Gram Power emerged in Rajasthan, India. To continue growth, Gram Power entered and won the LAUNCH: Energy Challenge, an initiative founded by USAID and its partners in 2011. The LAUNCH program identifies groundbreaking innovations in sustainable and accessible energy solutions and provides them with financial resources and project guidance.

“LAUNCH helped us launch!” Khaitan exclaimed. “It got us our first round of angel funding, helped us expand our network of advisors to leading figures in this sector from around the world… they worked very closely with us for 6 months after the event to help create access to the people and resources we needed to achieve our long and short term goals.”

Gram Power is now focusing on smart microgrids– localized electricity production centers that are smaller and more efficient. In May 2012, Gram Power launched India’s first smart microgrid in Rajasthan with great success, and are currently planning with the local Rajasthan government and the Central Government of India to increase microgrid deployments. They are simultaneously working with the Blum Center, USAID, the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), and TIER to rehabilitate 80 existing solar microgrids in Rajasthan. During the microgrid restoration, Gram Power and TIER will conduct extensive research evaluating different technologies and business models, in pursuit of a refined, sustainable method to provide reliable power to rural communities.

Gram Power is now focusing on smart microgrids– localized electricity production centers that are smaller and more efficient. In May 2012, Gram Power launched India’s first smart microgrid in Rajasthan with great success, and are currently planning with the local Rajasthan government and the Central Government of India to increase microgrid deployments. They are simultaneously working with the Blum Center, USAID, the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), and TIER to rehabilitate 80 existing solar microgrids in Rajasthan. During the microgrid restoration, Gram Power and TIER will conduct extensive research evaluating different technologies and business models, in pursuit of a refined, sustainable method to provide reliable power to rural communities.

By the end of 2012, Gram Power plans to expand MPower units and microgrids to other states in India such as Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Bihar.

Gram Power’s current projects are successfully providing reliable and affordable electricity for thousands of people, and Khaitan hopes to reach millions in the future. “We’re looking to continue deploying our smart grid system on existing microgrids,” Khaitan said. “Eventually tackling the existing Photo Credit: Gram Power national grid in India.”

Since it was established in 2006, the Blum Center has supported green innovation at UC Berkeley and around the world. Both the Big Ideas@Berkeley student competition and various faculty-led initiatives have produced projects that simultaneously improve the lives of individuals and benefit the environment.

Author:

Brittany Schell

Since it was established in 2006, the Blum Center has supported green innovation at UC Berkeley and around the world. Both the Big Ideas@Berkeley student competition and various faculty-led initiatives have produced projects that simultaneously improve the lives of individuals and benefit the environment.

Since the first Earth Day was celebrated on April 22, 1970, the modern environmental movement has taken shape. Over the past four decades, ideas about conservation, energy efficiency, and sustainability have come to the forefront of innovation.

In honor of Earth Day 2012, the Blum Center recognizes the vast array of green ideas that have been realized at UC Berkeley over the years, with the support of the center and other partners—from energy efficient stoves in Darfur, Tanzania and Ghana to a local bike share program, to solar energy projects and a proposal to “green” Berkeley’s campus.

This year, we have a whole new group of student contestants for Big Ideas@Berkeley. The contest winners will be announced on May 1, so stay tuned. For more information on this or any of the projects listed to the right, visit our website: http://blumcenter.berkeley.edu

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference.

Author:

Luis Flores

“We’re doing research in reverse,” explained student researcher Stephanie Ullrich. “We’re going from practice to theory.”

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference. These student researchers are not motivated by an imperative to publish, nor are they seeking a key to the gates of the academy; rather, these young scholars embody a paradigmatic shift that is at the core of the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor. Their research approach is informed by the contextual understandings developed in lecture halls and reading rooms but cedes formative authority to the inhabitants of the territories of poverty.

This semester, the Blum Center for Developing Economies welcomed five students from the Undergraduate Research Apprentice Program (URAP) to assist Professor Ananya Roy and research fellow Emma Shaw Crane in the development of a book on the recently held Territories of Poverty conference. These student researchers are not motivated by an imperative to publish, nor are they seeking a key to the gates of the academy; rather, these young scholars embody a paradigmatic shift that is at the core of the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor. Their research approach is informed by the contextual understandings developed in lecture halls and reading rooms but cedes formative authority to the inhabitants of the territories of poverty.

Stephaine Ullrich, a senior pursuing degrees in Peace and Conflict Studies and Media Studies, will work along with Anh-Thi Le, Aviya McGuire, Somaya Abdelgany, and Rebecca Peters, on the development of a book to be published next semester. In addition to a deep interest in global citizenship, Ullrich and her student colleagues share a new outlook on development practice and research.

Ullrich, who has worked on a variety of initiatives in Spain, Guatemala, northern India, and Uganda, has entered academic research after a great deal of in-the-field experience. While in India, Ullrich worked for Tata, one of the largest companies in India. During her time there, she conducted research aimed to increase the role of women in the management of water wells. She then completed her GPP practice experience in Uganda, where she worked with the Uganda Village Project on its “Healthy Villages” project. Ullrich worked with community-based organizations on efforts to increase virus awareness.

Student research assistant Rebecca Peters, a senior in International Development & Economics, shares Ullrich’s community-oriented approach. “I didn’t say, ‘I’m here to help you,’ but instead said, ‘let’s have a conversation,’” explained Peters, recounting her research approach in Cochabamba, Bolivia. During the summer of 2012, Peters conducted interviews and surveys in Bolivia to document rural access to water and sanitation services. She chose to work with Agua Para el Pueblo (water for the village), largely because of the value this NGO places on community relationships and participation. This commitment to listen rather than impose is among the transformative innovations of the GPP experience.

The cautiousness displayed by Peters and Ullrich results from exposure to the multitude of failed systems that together create conditions of poverty. The fear of inadvertently reinforcing these structures through their fieldwork is itself an attribute of the new generation of poverty scholars. Yet Peters and Ullrich do not allow consciousness to become disabling.

“Not becoming paralyzed is something that the minor really helps you with,” explained Peters. She reasoned that the GPP minor’s coursework on the ethics and morality of fieldwork allowed her to gather research while challenging north-south development paradigms.

In addition to their research with Professor Roy, Peters and Ullrich co-teach a student-led deCal course on water and international human rights. In their second semester of teaching, Peters and Ullrich expose 30 students to international discourses of human rights and water and their relationship to public policy, anthropology, sociology, economics, and even philosophy. In addition to examining case studies, Ullrich and Peter’s course bring in guest lecturers, and concludes with capstone group presentations.

The new generation of poverty scholars is bound neither by disciplinary borders, linear development theories, nor dichotomous understandings of poverty. Perhaps, more than progressing from practice to theory, this young group of scholars is forcing theory and practice to develop not as a binary, but together as one.

Abby Van Muijen discusses the Visual Notetaking DeCal and the ways in which this learned skill can improve the learning experience both in and outside of the classroom.

Author:

Christina Gossmann

Abby Van Muijen graduated from UC Berkeley in 2012 with a major in urban design. Now she works at the Blum Center as a Visual Communication Specialist, developing a new learning tool for the Global Poverty and Practice (GPP) minor and teaching a class on visual notetaking.

What is visual notetaking? Regardless of whether you’re putting a box around a word, improving your handwriting or sketching out entire pages, visual notetaking is all about breaking away from the conventional structure of notetaking that we’ve all fallen so helplessly into. We’re imagining alternatives to the spiral bound notebooks we all have–the ones filled with nothing but lines and lines of words that we will undoubtedly throw away at the end of the semester.

What is visual notetaking? Regardless of whether you’re putting a box around a word, improving your handwriting or sketching out entire pages, visual notetaking is all about breaking away from the conventional structure of notetaking that we’ve all fallen so helplessly into. We’re imagining alternatives to the spiral bound notebooks we all have–the ones filled with nothing but lines and lines of words that we will undoubtedly throw away at the end of the semester.

How did you start visual note-taking? I actually started visual notetaking while I was studying abroad. I was listening to guest lectures, working on projects, visiting sites and being given a lot of information, but the structure of the program made me feel like I didn’t need to remember everything. So I only wrote down the things I really wanted to remember. I would write words really bold or draw boxes around them and spent a lot of time doodling, drawing and listening. At the end of the trip, I had a sketchbook full of just the things I wanted to remember. But more than just having pages that sparked a lot of interest aesthetically, I felt like I was learning much more efficiently. I didn’t have to re-teach myself everything I had copied down in lecture anymore. I could look back at the visuals I had made and remember what I was thinking when I made them and studying felt more like reading a comic book than painfully trying to cram information into my brain.

What is The GPP coloring book? It is a compilation of all of my visual notes from Ananya Roy’s GPP 115 course from last fall when I took the class. This fall, students have been experimenting with it as a learning tool. Half of the book provides a visual outline of the lecture material so that students can sit in lecture and focus on understanding the main concepts, rather than worry about copying down every detail. The other half of the book consists of pages designed for students to fill in their own thoughts, questions, opinions and any other details that they feel are significant–the things they want to remember. The goal of the coloring book is not to get students to start bringing crayons to class, but rather to go beyond the black and white information they are presented with and add a bit of “color” of their own.

What is The GPP coloring book? It is a compilation of all of my visual notes from Ananya Roy’s GPP 115 course from last fall when I took the class. This fall, students have been experimenting with it as a learning tool. Half of the book provides a visual outline of the lecture material so that students can sit in lecture and focus on understanding the main concepts, rather than worry about copying down every detail. The other half of the book consists of pages designed for students to fill in their own thoughts, questions, opinions and any other details that they feel are significant–the things they want to remember. The goal of the coloring book is not to get students to start bringing crayons to class, but rather to go beyond the black and white information they are presented with and add a bit of “color” of their own.

You teach a class on visual note-taking at Berkeley. Who takes this class and how do you go about teaching? I took my first drawing class my sophomore year in college. On the first day, they told us to spend 15 minutes drawing whatever we wanted. I drew a tree that looked like a stick of cotton candy with a small, slightly ill-looking stick figure that I initially intended to be myself, but out of embarrassment, put a top hat on and labeled as Abraham Lincoln. Needless to say, it was an incredibly unimpressive effort. That was two years ago. I wasn’t magically bestowed with the ability to take notes the way I do. It was something I practiced every day, and taught myself how to do. I started Visual Notetaking 101 because I realized that this is a skill that people can learn. Visual notetaking can revolutionize your entire outlook on your education, as it did for me. Seeing your thoughts and ideas and opinions come to life, even if just on paper, is empowering. Rather than feeling sleepy and confused at the end of a lecture and having gained nothing more than a headache and a few pieces of binder paper that I won’t look at until the midterm. I now walk out of lecture feeling brilliant, creative and accomplished every day, holding on to a few pages of paper that I might cry if I lost. And that’s what I came to UC Berkeley to do, to be inspired each and every day not just by my professors, but my myself and my classmates.

How does the class work? Visual Notetaking 101 is designed so that everyone can participate. We have about 150 students from all different majors, ages, drawing abilities and walks of life. We meet every week for an hour and a half to take on a new element of visual learning beyond just visual notetaking, everything from fonts and page layouts to engaging presentation slides and résumé design. Each class starts off with a review, a quick lecture, a series of workshop activities, and for homework, we practice more. For the final review at the end of the semester students must come up with a project that is visual, academic and awesome. Last year’s projects were absolutely phenomenal–I’d encourage anyone interested to come check them out this year.

How does the class work? Visual Notetaking 101 is designed so that everyone can participate. We have about 150 students from all different majors, ages, drawing abilities and walks of life. We meet every week for an hour and a half to take on a new element of visual learning beyond just visual notetaking, everything from fonts and page layouts to engaging presentation slides and résumé design. Each class starts off with a review, a quick lecture, a series of workshop activities, and for homework, we practice more. For the final review at the end of the semester students must come up with a project that is visual, academic and awesome. Last year’s projects were absolutely phenomenal–I’d encourage anyone interested to come check them out this year.

The Final Review for Visual Notetaking 101 will take place on December 4th in the Blum Center classrooms.

How UC Berkeley professors, Ananya Roy and Tara Graham, are using social media in the classroom to help students become more engaged and foster a new academic community where all voices are heard.

Author:

Javier Kordi

Twitter has played a critical role in helping oppressed citizens challenge totalitarian regimes around the globe. Being able to transmit messages to a global audience within seconds, the site has led to a phenomenon that social scientists call “ambient awareness:” the notion that we can possess omnipresent knowledge of the whereabouts of friends, celebrities, organizations, and most recently, the course of history—all through 140-character blurbs of information known as “tweets.”

The micro-blogging service helped overthrow Mubarak in Egypt and challenge information blackouts in China, but in Ananya Roy’s Global Poverty and Practice class, it took on quite a different hue. While the sight of 700 students using their gadgets during class may resemble anarchy for some, a new sort of classroom community was being fostered through the use of Twitter.

Professor Roy described her mission as establishing “a democratic means of communication, [to] change how we learn and how we interact.” No longer restrained by the convention of hand-raising or one’s shyness, students were given the opportunity to have their ideas heard. In the realm of Twitter, students are free to exchange ideas, challenge others, and even alter the course of the lecture.

Professor Roy described her mission as establishing “a democratic means of communication, [to] change how we learn and how we interact.” No longer restrained by the convention of hand-raising or one’s shyness, students were given the opportunity to have their ideas heard. In the realm of Twitter, students are free to exchange ideas, challenge others, and even alter the course of the lecture.

As Professor Roy delivered her lecture on Jeffery Sachs and William Easterly, a live Twitter feed was projected on the screen behind her. Grouped under the hash-tag #GlobalPov, a mosaic of ideas and commentary materialized behind Professor Roy, back dropping her lecture and adding a new dimension of interaction.

Tara Graham, the architect of this project, explains how it seeks to “encourage a many-to-many lecture”, where “the feed becomes the focal point” of the classroom. Chipping away at the tradition of hierarchical education, the Twitter project restructures social relations within the classroom.