The Hacking4Local course at UC Berkeley empowers students from diverse disciplines to tackle complex social issues in Oakland, such as affordable housing and equitable health access. Through interviews, community engagement, and interdisciplinary collaboration, students design real-world solutions while gaining professional skills in teamwork, communication, and navigating ambiguity.

When fourth year media studies student Erik Phillip came across a flyer for the Blum Center’s Development Engineering course Hacking4Local, he was interested but wary.

“I thought I’d be the only undergraduate and the only non-engineer,” he said. “That was a terrifying combination.”

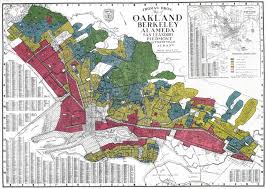

But Phillip, who was born and raised in Oakland and is proud member of its African American community, decided to go to the course’s information session anyway because of the changing economics and demographics of his hometown. He quickly learned two things: first, that the instructors of Hacking4Local sought students from multiple disciplines; and second, the course’s aim was to teach students how to design solutions for Oakland on complex topics such as homelessness, low-cost housing, and high-quality education.

Phillip had no delusion that he would walk away from the course in May with a solution to the affordable housing crisis, which was the subject he chose to focus on with a team of five students. Rather, he said, his expectation was and remains “to learn how the affordable housing crisis came about and how the systems around it works.”

Mostly, he said, he has been amazed how much he has learned due to course’s unusual approach, which combines pedagogies in interdisciplinary project-based learning, human-centered design, the flipped classroom, and student team learning as well as input from a half dozen professors and instructors, including Public Policy Professor Dan Lindheim, former City Administer of Oakland, and guest lecturers such as Steve Blank, whose Lean Launchpad and Lean Startup methodologies have been embraced by Silicon Valley startups and the National Science Foundation Innovation Corps.

Hacking4Local is a hacking course only in name. Its first priority is framing a problem to be solved. While some of the student teams exploring local transportation emissions, equitable health access, and Oakland hills fire mitigation are using algorithms and data analysis in their inquiries—the primary method of the course is gathering information through research and interviews (at least five per week), synthesizing that information into eight-minute presentations (during which the instructors serve as a council of critics), and iterating and refining ideas.

Students get the real-world experience of working on problems identified by local government agencies, nonprofits, or companies. And at the end of the course, they must deliver their solutions, which can vary—a physical product with a bill of materials cost and a prototype, a web product with users, a mobile product with working code and users, or a service or policy solution with an implementation plan and anticipated cost of delivery.

The instructors—Development Engineering Lecturer Rachel Dzombak, Mechanical Engineering Professor Alice Agogino, Public Policy Professor Dan Lindheim, and Haas School of Business Entrepreneurship Lecturer Steve Weinstein—have assembled a reading list that familiarizes students with how to work on complex social issues, consider their historical and political contexts, and engage with communities affected by a variety of overlapping problems. The class introduces students to methodologies such as the “mission model canvas,” “customer discovery,” and “agile engineering,” and exposes them to guest speakers who have experience in Oakland communities and politics.

“The course is about design for the public good and helping students hone their skills on both qualitative and quantitative methods for understanding stakeholder needs and getting community feedback on possible solutions,” said Agogino, who serves as chair of the Graduate Group in Development Engineering and the Blum Center’s education director. “Students learn to value the complexities of government, the people it serves, and other stakeholders. They learn that as with any organization, there is a difference between formal power and informal power.”

Added Dzombak: “The class challenges students to think through the root cause of problems, the systems in which problems exist, and to understand potential consequences of interventions. Students are learning to navigate ambiguity using a human-centered process and gaining critical knowledge about politics and governance, which is rare for an engineering course.”

During one four-hour class in March, Phillip and his affordable housing teammates—Surabhi Yadav, a master’s student in Development Practice, Ben Truong, an undergraduate cognitive science student, and Andre Balthazard, an undergraduate operations research and management sciences student—presented their findings on why affordable housing in Oakland has been inadequate and what they might devise for their client, the Strategic Urban Development Alliance (SUDA). The team, which has conducted over 60 interviews with Oakland residents and community stakeholders, argued that one of the key problems in Oakland real estate is the lack of involvement from residents on issues of equitable development.

To this point, Steve Blank quipped: “The joke about community meetings about real estate development is they’re filled with retired people and stakeholders.”

The team members nodded. Phillip pointed out that since 2010, the Bay Area has added 722,000 jobs but only 106,000 housing units.

Blank pressed the group: “Yes, but there are multiple housing crises. Which one are you solving for?”

In an interview after the class, Surabhi Yadav said her team is aiming to solve for longtime residents who feel they are at risk of eviction or their children will be unable to live nearby. Yadav noted that although many longtime residents do not have individual financial or political power, they could have collective power.

“Unionizing power is time consuming to create,” noted Yadav. “Still, we’re questioning whether we can develop tools that will help Oakland residents harness their collective power. And we’re trying to figure out if we can help SUDA measure and develop what effective community development looks like.”

Yadav, who co-designed and co-taught a similar course for engineering students at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, said classes that involve multiple disciplines and hands-on learning are good at developing students’ professional skills in communication, teamwork, managing priorities, and navigating ambiguities.

“You have to learn how to take feedback in these kinds of courses and go with the flow,” explained Yadav. “It’s about structuring uncertainty, because the logistics and pedagogy and learning outcomes of the class are very different.”

Barbara Waugh, an executive in residence at Haas, Oakland resident, and guest lecturer for Hacking4Local, sees another strength of the course: higher team performance.

“Diverse teams under- or outperform homogeneous teams depending on whether they ignore or leverage their diversity,” she said. “Shared passion for a project can be a great lever and our Hacking4Local teams demonstrate both the passion and the higher performance that leveraging diversity offers.”