April is the cruellest month, breeding

Lilacs out of the dead land, mixing

Memory and desire, stirring

Dull roots with spring rain.

So began T. S. Eliot’s 1922 poem The Waste Land about madness and death, trauma and hope, and the confusing world of the early 20th century. A century later, we find ourselves in another cruel April, one witnessed and suffered by the whole world due to the coronavirus disease pandemic: COVID-19.

At the Blum Center, we like all centers and departments and schools have been shifting to online teaching, advising, and working—as well as closely following the spread of the disease to low-income countries and regions. As you know, the news is bad. The COVID-19 crisis threatens to disproportionately affect developing countries, not only as a health crisis but as a devastating social and economic crisis.

For poor countries, the socioeconomic fallout from COVID-19 could take years to recover from, according to a United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) report released on March 30. The report warns that income losses are expected to exceed $220 billion in developing countries, and nearly half of all jobs in Africa could be lost:

“With an estimated 55 per cent of the global population having no access to social protection, these losses will reverberate across societies, impacting education, human rights and, in the most severe cases, basic food security and nutrition. Under-resourced hospitals and fragile health systems are likely to be overwhelmed. This may be further exacerbated by a spike in cases, as up to 75 per cent of people in least developed countries lack access to soap and water.”

But there is room for hope and more for action. As Berkeley Economics Professor Edward Miguel points out in a recent Cal news article, Africa has certain strengths for combatting COVID-19. Unlike much of Europe, the median age of many African countries is young: 20 years old. That could mean the proportion of people who die could be much lower in African countries. That might also be true for India, where the median age is 26.8. Miguel, who is faculty director of the Center for Effective Global Action, also notes two other strengths: Even though Africa is rapidly urbanizing, a large share of the population still lives in rural areas, where social distancing is more possible.

He continues: “Another strength is the regional experience in sub-Saharan Africa dealing with Ebola in the last five or six years. There was infrastructure put in place to screen people, to contain an epidemic. I know Ebola and COVID-19 are quite different, but that capacity building may help now. And Africa has 30 years of dealing with the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Partially due to local initiatives, partially due to global aid initiatives, African health systems are much stronger than they were 20 years ago, or 15 years ago.”

Still, there is much to fear and prepare for. Multilateral agencies, international foundations, and all manner of aid organizations focused on poor countries are moving funds and resources toward saving lives. A UNDP-led COVID-19 Rapid Response Facility has been launched with an initial $20 million; however, UNDP anticipates a minimum $500 million need to support 100 countries. The International Monetary Fund and World Bank have urged debt relief to poorer countries hit by the coronavirus pandemic, with bilateral creditors playing a major role.

“Many countries will need debt relief. This is the only way they can concentrate any new resources on fighting the pandemic and its economic and social consequences,” said World Bank President David Malpass at a March 26 meeting. Malpass reported that the bank has emergency operations under way in 60 countries and its board is considering the first 25 projects valued at nearly $2 billion under a $14 billion fast-track facility to help fund immediate healthcare needs. Meanwhile, the State Department and the U.S. Agency for International Development have pledged $274 million in health and humanitarian assistance. And Bill Gates is spending billions to set up factories that will make the seven most promising coronavirus vaccines.

Around the UC Berkeley campus, there has been a plethora of COVID-19 responses that will help developing and developed countries alike. The first target of a new AI research consortium, the C3.ai Digital Transformation Institute (of which I am co-director), is research that addresses the application of AI and machine learning to mitigate the spread of COVID-19. Bioengineering Professor and Blum Center Chief Technologist Dan Fletcher and his lab members have come up with a way to adapt the fluorescence microscopy function of their mobile phone microscope, the CellScope, to assist in rapid testing. Fletcher and his colleagues have been working with virology expert Melanie Ott of the Gladstone Institute and CRISPR pioneer Jennifer Doudna, among others, to provide the rapid remote detection portion of the team’s CRISPR-based COVID-19 RNA detection method. Dr. Bertram Lubin, the Blum Center’s and College of Engineering’s senior advisor in health, has been working with a coalition of UC Berkeley engineers led by Mechanical Engineering Professor Grace O’Connell, emergency room doctors, and critical care pulmonologists to turn sleep apnea machines into ventilators. And Development and Mechanical Engineering Student Paige Balcom is in Uganda (where there are 55 ICU beds with oxygen for a population of nearly 43 million people), using her social enterprise Takataka Plastics to manufacture face shields for doctors and staff in the town of Gulu.

In this issue of the Blum Center’s Innovation Chronicle, we salute these and others working stop the spread of COVID-19 and educating the next generation of Berkeley changemakers. Fiat Lux!

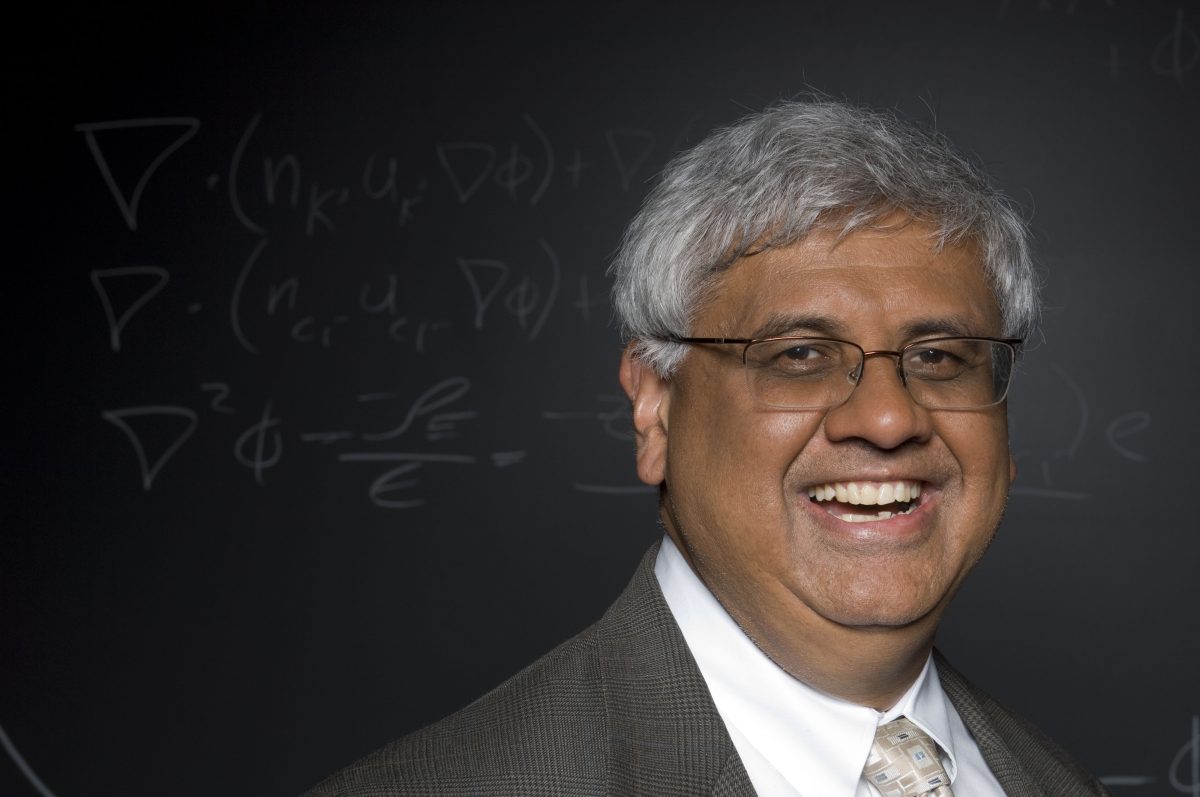

Shankar Sastry is Faculty Director of the Blum Center for Developing Economies and Siebel Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, Bio-engineering and Mechanical Engineering at UC Berkeley.