In IAS 120, Students of the GPP Minor Learn the Skills to Spread Global Awareness

By Luis Flores

“It’s a practical course,” explained Royce Chang about professor Tara Graham’s Field Reporting in the Digital Age: Using Media Tools for Social Justice. “I don’t think we get enough of that here at Berkeley.”

Professor Graham’s course trains students in Berkeley’s Global Poverty and Practice minor to use the Internet and social media as tools for global engagement. The course is an all-inone tool kit for global awareness.

Last year, students received training in everything from film, photography and creative writing to web design. “The course was valuable because it trains you to look for things and to look for the best and most ethical way to go about acquiring material,” remarked Royce. Professor Graham is teaching the class again this semester.

Royce, a history major concentrating on ancient Greece and Rome, is currently working on developing media content for One World Futbol at Berkeley, an NGO that is working to spread global and community awareness among local K-8 students through sports. He continues to believe that no matter the initiative, the spread of awareness is a vital part of enacting positive change. To this goal, online media is a valuable tool.

Ryan Silsbee, another of professor Graham’s students last year, has since graduated and is completing a four-month organic agriculture apprenticeship with Real Time Farms in Hawaii. The importance of the media skills learned in professor Graham’s class are obvious by looking at his website: a clean site with vivid photographs, concise, creatively written updates and interactive maps and guides. His site allows readers to engage with his mission of promoting healthy and organic agriculture. “Spreading information and just getting people interested in where their food comes from and how it is grown is the first step,” Ryan said.

The theoretical courses in the GPP minor set Ryan on a path to change American agriculture, and Professor Graham’s course gave him the tools to start making those changes. “I want people to step out of their busy lives, take a look at agriculture in the United States and decide for themselves if they think something should be changed,” he explained.

Many of professor Graham’s students, like Danika Kehlet, were first able to put these skills to use during their summer practice initiatives. Armed with a small flipcam, Danika set out to chronicle her work promoting female development in Quito, Ecuador. Her lively blog illustrates her experience through the use of videos, photo collages and engaging blog entries.

This semester, Professor Graham is training a new group of GPP students in a similar course: Using Media Tools for Global Poverty Action. Practical courses like these are training the next generation of tech-savvy global citizens. Exposure to the development possibilities of social media is empowering and inspiring students.

“It is very inspiring to know that something I create, write, photograph, film, or document can change the way people view their world,” Ryan said. “If enough people see it, you can change society.”

World Day of Social Justice

by Brittany Schell

February 20th marked the annual World Day of Social Justice. “Social justice is an underlying principle for peaceful and prosperous coexistence within and among nations,” states the website of the United Nations. “We advance social justice when we remove barriers that people face because of gender, age, race, ethnicity, religion, culture or disability.”

In 2007, the UN General Assembly declared February 20th of each year the “World Day of Social Justice,” to recognize groups around the world working to fight poverty and promote gender equality, access to health care and other initiatives that advance development and human dignity.

Here at the Blum Center, our students and faculty work actively toward these goals. Each year, we offer fellowships to students studying in the Global Poverty and Practices minor at UC Berkeley to help fund their summer fieldwork experiences.

Fieldwork has ranged from supporting tenants’ rights in New York City to providing access to clean water in India; improving child nutrition in Guatemala and addressing poverty in Vietnam; working with opium addicts in Afghanistan and HIV/AIDS prevention work in Ghana; and even building community bread ovens in Tanzania. Our students have helped advance the foundation of social justice through hands-on work, making concrete differences in communities across the world.

Last summer, 40 students received fellowships from the Blum Center. Check out the map to see the wide range of countries where our fellows volunteered their time and energy.

Big Ideas @ Berkeley 2011 Spotlight: BareAbundance

By Javier Kordi

Upon entering Berkeley’s all-you-caneat dining halls, students undergo a strange biological transformation: their eyes seem to swell, far exceeding the size of their stomachs. Seven servings later, a tray full of half eaten entrées stares back at their defeated gazes before getting disposed of in the garbage. This propensity to waste is not limited to university dining halls. Every day, 260 million pounds of food are wasted while 50 million Americans go hungry. Witnessing this incongruity first hand, Global Poverty and Practice students Komal Ahmad, majoring in International Health and Development, and Jacquelyn Hoffman, majoring in Gender and Women’s studies, created BareAbundance—an organization that addresses the inequitable food distribution that causes millions of Americans to suffer every day.

When food is neither consumed nor sold, or is nearing its expiration date, the organization sweeps in to intervene before it is tossed into a landfill. Receiving excess healthy food from a wide network of sources, BareAbundance redistributes this excess to people in need. Last year, BareAbundance signed a contract with Cal Dining, securing the excess foods from four dining halls and 10 on-campus cafes and restaurants. Currently, this food is being delivered

to an afterschool program at New Highland School in East Oakland, where 70 percent of students are on free or reduced lunch.

Komal, one of the founders of BareAbundance, explains that the after-school program is about more than providing food; it’s also about food education. For a community lacking access to farmers’ markets, the nutritional model of the food pyramid is sometimes hard to meet. In addition to providing much-needed sustenance, the after-school program teaches “food driven values through an experiential method where [the students] consume and cook the food.”

Take one of the program’s three-day examples: children were first given donuts and asked to write about how they felt in their journals. Initially abounding with energy, the children reported stomachaches and lethargic feelings a few hours later. A similar feeling was reported the next day when the kids ate pieces of cake. On the final day, the children were given a luscious piece of fruit. They wrote in their journals that, not only did it taste good, but it also provided sustained energy without a sugar crash. This technique trains children to recognize the importance of a healthy diet through direct engagement.

Last year, BareAbundance was selected as a winner of Big Ideas @ Berkeley, a campus-wide innovation competition managed by the Blum Center. A recipient of the Social Justice and Community Engagement award, the organization received funding for transportation, food storage, website creation and publicity, allowing it to grow dramatically. Komal humbly described how the Big Ideas @ Berkeley grant “legitimized our organization…our idea.” It compelled the founders to make their model of food redistribution a reality: as Komal said, it was “both a pat on the back and a kick in the ass.” In the future, Komal hopes to establish a nationwide food recovery network to save and distribute excess food from college campuses around the country.

ECAR Safe Water Initiative: A New Solution to an Old Problem

By Javier Kordi

Abandoned arsenic water filters litter the village of Amirabad, India like archaic ruins. For years, the community has seen foreigners come and go, bringing the promise of clean water and leaving behind hollow philanthropic gestures. Arseniccontaminated ground waters have created the largest mass poisoning in human history. In Bangladesh alone, 40 million people are exposed to arsenic through their tube wells. From Latin America to Asia, arsenic-laden water has plagued the lives of millions.

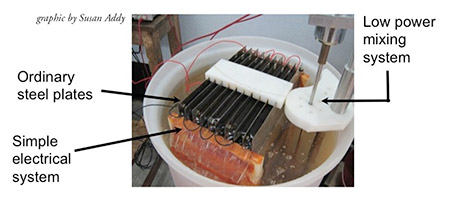

Working in conjunction with the Blum Center for Developing Economies and the Lawrence Berkeley National Labs, professor Susan Addy and her team of scientists have brought something new to the water table: a sustainable model for water purity—the Electrochemical Arsenic Remediation project (ECAR).

ECAR differs from its predecessors in its mode of arsenic extraction. The elusive arsenic particles cannot be removed with traditional filtration—they will not settle or get retained. ECAR works by literally grabbing these particles and dragging them to the bottom of a water basin, separating them from the clean H2O. It is a simple procedure.

First, a steel plate is placed into a tub of water. Then an electrical current is passed through the steel, creating millions of rust particles. As the rust

expands, it electrochemically binds to arsenic. The rust-bonded arsenic settles to the bottom of the basin and the final step—adding Alum, a water

coagulant—allows the amalgamation and separation of the poison. The 100 liter prototype produced clean water that was indistinguishable from bottled water, using only as much energy as a CFL light bulb.

But even the most brilliant of technologies cannot succeed if they are not embraced and maintained by the local community. “The technology is maybe 20 percent of the problem,” professor Addy said. “The social situation, making it work sustainably, is maybe 80 percent of the problem.” Often times, water projects fail because they are a one-time gift from a donor. Working with financial institutions, a social marketing firm and local governments, the ECAR project will make the delivery of clean water part of the community’s livelihood. The product of ECAR (clean water) will become a good, to be sold and profited from in an open market, thus creating an economic incentive for continued production.

Professor Addy explained the plan for this year: “We’ve got two pilot projects planned this year that will serve water to about 2,500 students, maybe one to two liters per day, operating for several months.” As children learn about water safety in their classrooms, the neighboring water plant will transform the school into a community center—a nexus for health and education. Ultimately, the plant will provide jobs for the local people. While providing free water to children, the excess that is created can be sold to the community. ECAR aims to become a self-sustaining water plant, both economically and technologically. Because the government has an interest in increasing student enrollment, professor Addy believes there is potential for partnering with India’s Ministry of Education to further subsidize the project.

At the end of February, two scientists, Christopher Orr and Siva Rama Satyam, will depart from Berkeley to spend six months in India testing out the new 500 liter prototype. After working with a manufacturer in Mumbai, the prototype will be shipped to Jadavpur University in Kolkata for a few months of testing. If all goes well, this prototype will be moved to the school in Amirabad, India, where it will provide six months of free water to local school children. According to Sivarama, local governments and communities are eager to adopt the technology, particularly after the success of the initial model. With continued successes, the full implementation of ECAR and the cleansing of the water table will soon be a reality.

Design for Sustainable Communities Course

By Brittany Schell

Professor Addy also teaches a course at UC Berkeley, Design for Sustainable Communities. The class gives students hands-on experience in the design and implementation of projects meant to improve the sustainability of communities in developing countries.

The students work in teams throughout the semester on practical projects, with guidance from professor Addy and other experts. The class, a mix of graduate and undergraduate students from various majors at Berkeley, meets twice a week to discuss their own projects as well as explore the methods of successful innovators.

“One of the most pressing challenges of the new century is to harness the extraordinary force of technological innovation…and make its benefits accessible and

meaningful for all humanity,” professor Addy said to begin class, quoting former UN Secretary General Kofi Annan.

Cost effective, creative solutions to problems like unemployment and the lack of water and electricity in villages—like professor Addy’s ECAR water initiative—provide a new area of opportunities for businesses and social entrepreneurs. It’s innovation for the 90 percent, she told her students.