By Tamara Straus

What does it take to help hard-to-employ people in the Bay Area find steady, decently paying jobs? According to Veronica Barron Villegas ’18, a Global Poverty & Practice graduate who works at The Bread Project, it requires receptive employers, well trained employees, and lots of follow up.

Founded in 2000 by Lucie Buchbinder, a homeless advocate and Holocaust survivor, and Susan Phillips, a social worker involved in affordable housing, The Bread Project is known within employment development circles for its model of targeted persistence, which includes a rigorous bakery training program, extensive workplace readiness coaching, on-the-job experience, employer outreach for job placement, and long-term follow-up support. Eighteen years ago, Buchbinder and Phillips acted on a hunch. They knew that the baking industry paid above minimum wage and offered a career ladder. With this in mind, they approached Michael Suas of the San Francisco Baking Institute, who agreed to train their low-income clients and provided space and equipment for classes at cost.

Since that time, the Berkeley nonprofit has trained 1,800 individuals for the baking sector through dozens of partnerships with Bay Area chefs like Mark Chacon, agencies like the City of Berkeley Office of Economic Development, and employers such as Whole Foods and Semifreddis. Trainings are long by comparative standards: three to four weeks. And follow-up services are beyond the standard: 15 months, which include six rounds of job search assistance and career counseling.

The results for a small nonprofit are extraordinary—averaging an employment rate of 83 percent, a graduation rate of 85 percent, and a job retention rate of 80 percent.

Trent Cooper, The Bread Project’s Program Manager, believes the high employment rates stem from the high-touch training and post-graduation services. “If you see our boot camps, you see how closely we interact with each student. Upon graduation, we provide 15 months of follow-up services, with outreach at one, three, six, nine, 12, and 15 months. This is time consuming and expensive, but we’re able to help participants longer.”

The Bread Project serves people who are the first to get turned down by employers—immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers, formerly incarcerated individuals, and people with disabilities as well as those with employment barriers due to language, addiction, unstable housing, and childcare. In 2017-2018, 79 percent of participants relied on public benefits, 21 percent had zero income coming into the program, 100 percent were low income, and the participant pool was 61 percent female and 32 percent male. Most trainees come from Oakland, Berkeley, and Richmond. And many lack independent housing and are dependent on public housing, friends, family, shelters, or transitional lodging.

Foundation grants, individual and corporate donations, and city funding keep The Bread Project afloat as well as a well-honed social enterprise model. Its University Avenue kitchen produces sweet potato buns for the high-end San Francisco restaurant International Smoke and mixes up about 3,000 pounds of cookie dough per week for DOUGHP. There’s also a food business incubator program; The Bread Project focuses on renting out its kitchen to minority-run businesses. All of this pays for the cost of the long boot camps, from which about 120 people graduate annually.

To support nine low-income Berkeley residents pass through the training program, UC Berkeley’s Chancellor’s Community Partnership Fund recently awarded The Bread Project a grant. The project, in collaboration with the Blum Center’s Global Poverty & Practice (GPP) minor, aims to strengthen the university’s ties to the City of Berkeley through employment development opportunities and engages GPP student interns in poverty alleviation work.

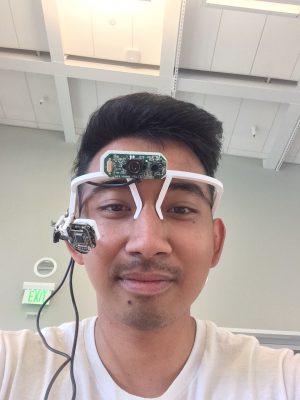

Jasmine Tsui, a UC Berkeley global health major and Global Poverty & Practice minor, said her summer internship at The Bread Project has given her a front seat row to the Bay Area’s widening income gap. “I’ve seen what it means to be looking for a job and have no computer to do job research and applications. Employment barriers like those are real, but The Bread Project is surmounting them through a range of supports.”

Tsui, who has been working closing with Barron Villegas, The Bread Project’s employment and graduate services manager, has been on the phone with graduates for much of her summer internship. “I’ll call graduates five, six times,” said Tsui. “I’ll leave messages, emails, and texts, and once I get them on the phone, I ask them how they are, if they need a job, and make an appointment to come in right there.”

Tsui’s summer internship colleague, Emily Lui, a UC Berkeley economics major and Global Poverty & Practice minor, also has been impressed by the personalized services. “There’s a lot of emphasis on trying to find people who graduate from the program a job—and a job they actually want. Earlier this month, there was a hiring event where different reps from different Whole Foods came in and did onsite interviews.”

Barron Villegas, who like Lui and Tsui got her start at The Bread Project as a GPP intern, said she is currently developing and strengthening employer partnerships with Noah’s Bagels and High Flying Foods.

“The reason The Bread Project has the outcomes it does is because we build relationships with both employers and job seekers,” said Barron. “Our clients walk away with a specific skill set and into a more specific job market. They learn interview skills, resume writing skills, and other job readiness skills. They also earn a ServeSafe certificate from the State of California. Employers want all of that.”