By Tamara Straus

For the creators of the UC Berkeley course Eat.Think.Design, two things are certain. First, the United States is facing a food and nutrition crisis, with rocketing rates of diabetes, hunger, and health disparity. Second, graduate students today—from fields as different as public health, business, information technology, and engineering—want their education to be more hands-on, more interdisciplinary, and more “impactful” to society at large. In the case of the Eat.Think.Design course, they want to spend class time not just learning about food and nutrition problems, they want to devise actual food and nutrition solutions.

For the creators of the UC Berkeley course Eat.Think.Design, two things are certain. First, the United States is facing a food and nutrition crisis, with rocketing rates of diabetes, hunger, and health disparity. Second, graduate students today—from fields as different as public health, business, information technology, and engineering—want their education to be more hands-on, more interdisciplinary, and more “impactful” to society at large. In the case of the Eat.Think.Design course, they want to spend class time not just learning about food and nutrition problems, they want to devise actual food and nutrition solutions.

This may sound grand, but for the course’s three instructors— Jaspal Sandhu, a UC Berkeley lecturer in design and innovation; Nap Hosang, a longtime Kaiser Permanente medical doctor and UC Berkeley School of Public Health instructor; and Kristine Madsen, an associate professor in the Joint Medical Program and Public Health Nutrition at Cal’s School of Public Health—there is nothing grand or inappropriate about letting students attempt societal solutions while in school.

“The reason we emphasize experiential learning is because it has proved to be more effective,” says Sandhu, who is also a partner at the Gobee Group, a consulting firm he runs with two other multilingual Fulbright scholars with UC Berkeley roots. Sandhu speaks Punjabi, Spanish, Mongolian, and English, and prior to Gobee worked with the Mongolian Ministry of Health designing mobile health information systems.

Sandhu emphasizes that his students’ backgrounds demand more than lecturing. Among the 25 people enrolled in Eat.Think.Design this spring, many have relevant work experience. At least three have started their own companies, several have worked for big companies like IBM, Deloitte, and Eli Lilly, and most have about five years under their belts working for government agencies or large nonprofits. “To keep the attention of such students,” says Sandhu, “we need to give them actual problems to focus on.”

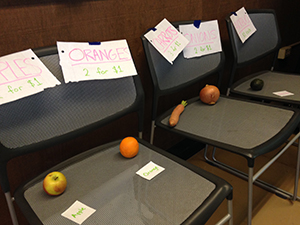

Working in interdisciplinary teams of three under an instructor, Eat.Think.Design students spend the bulk of the semester on one project, conducting ethnographic and market research, investigating models, and constantly devising and then revising potential solutions. Members of last year’s class, for example, streamlined SNAP federal nutrition benefits payments at San Francisco’s Heart of the City Farmer’s Market, worked with the Kossoye Development Program in Ethiopia on strategies to make home gardening more accessible, and built a pilot program with Partners In Health: Navajo Nation to test a pop-up grocery store in areas that are one hour’s drive from fresh food. Although the project in the Navajo Nation helped COPE to receive a three-year, $3 million REACH grant from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention to pursue healthy eating programs in the vast American Indian territory—Hosang argues that the course is not designed to incubate social innovations per se.

“Our goal is to incubate innovative people—people who can be influencers in the public health sector,” he says. Hosang, who has served as head of the interdisciplinary online MPH degree program for the past 15 years and executive director of the Interdisciplinary MPH degree program since 2010, is not subtle in his criticism of public health teaching. “Most academics are in a silo,” he said, “and their silo has driven them more and more into their specialist thinking.” Yet this specialist thinking, Hosang argues, is running counter to the view that public health is enmeshed in almost every field—from architecture and transportation, to product design and education. “We need to change the way public health professionals approach problems,” said Hosang, “and we need them to be in touch with people from other disciplines to inform their problem-solving processes.”

Hosang and Sandhu started working on their public health course in October 2010, after Hosang read Sandhu’s dissertation on public health design research in rural Mongolia and was impressed by the combination of grassroots and trial-and-error learning. In the spring of 2011, they launched their course, with financial support from the Blum Center for Developing Economies, which seeds interdisciplinary, social impact courses on campus. Madsen joined the course in 2014 when the focus narrowed from designing innovative public health solutions to designing innovative food solutions. In a March 2015 article in the American Journal of Public Health titled “Solutions That Stick: Activating Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration in a Graduate-Level Public Health Innovations Course at the University of California,” the three instructors describe how their approach is part of a much-needed pedagogical shift. They write:

“A Lancet Commission, convened to discuss the education of health professionals in the 21st century, argued that educational transformation is critical to meet the public health problems we face in this century. Specifically, the commission called for a higher level of learning, moving beyond informative learning, which transmits knowledge to create experts, to transformative learning, which transmits leadership attributes to create agents who can successfully implement change.”

Sandhu explained that when he and Hosang came up with the idea for the course, not only was this “change agent” approach novel but no one was applying design thinking or human-centered design approaches at the School of Public Health at UC Berkeley. (He describes those approaches as ones that enable teams to systematically develop novel, effective solutions to complex problems.) Yet Sandhu says it is clear there’s a demand for this kind of problem solving.

Sandhu’s proof is the continual over-enrollment in and rave reviews of his course. This year, 60 students applied for 25 spots. And for the past four years, 40 percent of students indicated it was the “best course” they took at UC Berkeley, with the other 40 percent stating it was in the “top 10 percent” and the remained saying it was in the “top 25 percent.”

Sandhu’s proof is the continual over-enrollment in and rave reviews of his course. This year, 60 students applied for 25 spots. And for the past four years, 40 percent of students indicated it was the “best course” they took at UC Berkeley, with the other 40 percent stating it was in the “top 10 percent” and the remained saying it was in the “top 25 percent.”

Christine Hamann, a MBA/MPH candidate who took Eat.Think.Design in 2014, confirmed that “the teaching team is phenomenal—both in terms of the academic leadership and the mentoring of graduate students.” She also confirmed that she and her fellow students want “practical challenges in graduate school,” adding “we are tired of theory.”

Hamann is one of the many students who has brought past work into the classroom. Before grad school, she worked for seven years at Partners In Health, most recently on the nonprofit’s COPE Project in the Navajo Nation. She said the course forced her to look at Navajo Nation residents’ consumer needs around food and nutrition—and to see food less as a supply issue and more of a demand issue. “Traditional public health approaches focus on supply, but that is why you see programs that don’t meet the needs of the community,” she said.

Hamann and the three other graduate students opted not to focus on the best truck routes to bring fresh produce into the 27,000 square mile territory—and instead focused on seeing what citizens there want to consume and what can last in what is a food (and actual) desert. During the summer of 2014, with funding from the Blum Center, Hamann created pop-up grocery stores in Navajo, to determine which food items were most in demand and could help reduce chronic diseases like diabetes, which affects 20 percent of residents. This exploration helped lead to the aforementioned $3 million CDC grant for COPE.

As to why so many Cal students are so focused on food and nutrition, Hamann has this to say: “From a public health perspective, I think we’re seeing the ramifications of the American diet play out in really scary chronic disease indicators.” She also noted that there is a general heightened awareness of food systems—“of where food is coming from, the corporations that own it, and the detrimental effects those relationships can have on both health outcomes and business models.” Third, Hamann said a growing number of students want to see tech innovation applied to less wealthy and less urban populations—“the people,” she said, “who need it.”

Then, there are the galling statistics: Americans throw out an estimated 40 percent of food grown per year. An estimated 50 million Americans do not have access to enough food. As of 2012, about half of all adults—117 million people—have one or more chronic health conditions, such as heart disease, stroke, cancer, diabetes, obesity, and arthritis. And childhood obesity has more than doubled in children and quadrupled in adolescents in the past 30 years.

Sandhu is aware that a course on food innovation is well timed at UC Berkeley. In 2013, UC Berkeley’s College of Natural Resources, the Goldman School of Public Policy, the Graduate School of Journalism, Berkeley Law, and the School of Public Health joined forces to create the Berkeley Food Institute to improve food systems locally and globally. A year later, UC President Janet Napolitano launched the UC Global Food Initiative—to prompt all 10 campuses, UC’s Division of Agricultural and Natural Resources, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab, and a consortium of faculty, researchers, and students to address food security, nutrition, and sustainability issues. Even BigIdeas@Berkeley, the annual student innovation prize, has a contest category on food systems innovation.

“Our timing is either well forecasted or extremely lucky,” said Sandhu.

Eat.Think.Design may be a popular course—and may inspire copycats—but both students and instructors are quick to point out that the course cannot serve as a model for every class. “It is difficult to take more than one experiential class per semester,” said Hamann. “The time commitment with fellow students and with our client is just too big.” Amy Regan, who took the course in 2013 and now works with the San Francisco Unified School District’s Future Dining Experience program, agrees that “compromising and agreeing on the best approach among a group takes time.”

For instructors, Professor Madsen estimates the course requires one and a half to two times more time than an average School of Public Health offering, because she, Sandhu, and Hosang each mentor three student groups during and after class time. The three instructors also spend time cultivating their connections to bring in student projects from nonprofits and government agencies. During the class on Feb. 4. 2015, 16 pitches were made by representatives of various organizations, including California Farm to Fork, San Quentin State Prison, and Project Open Hand. “Much more work goes into creating the class because of all the connections to be made,” said Madsen.

And very little is scripted. This gives the course the feeling of a kind of pedagogical startup, exciting but uncertain. Madsen said this atmosphere comes with a distinct disadvantage for professors. “You have to admit you don’t know as much,” she said. “If your identity is wrapped up in being an academic expert, this won’t work; you’ll always default to the more narrow but comfortable path.”

For Sandhu and Hosang, who are adjuncts, there is less face to lose. “I think over the last seven years, since the start of the Great Recession, there’s been a transformative energy happening in higher education,” said Hosang. “It’s coming from the younger generation who see the world has changed and who no longer see college as a ticket to success. That’s where this move toward an interdisciplinary, hands-on approach is coming from.”