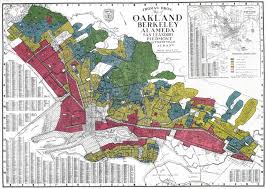

Engineers have the potential to play an instrumental role in helping marginalized communities improve their living conditions. That is because engineers are adept at applying the principles of science and math to develop socio-economic solutions. For much of the 20th century, people trained in history, law, and sociology were seen as the primary actors for alleviating poverty. Increasingly, engineers who can assimilate these and other disciplines are today’s poverty alleviation strategists—aware that today’s technological leaps forward are creating inequalities that need multiple forms of redress.

The Development Engineering PhD designated emphasis was launched with this in mind. An interdisciplinary training program for UC Berkeley doctoral students from any field, the program requires dissertation research on the application of technology to address the needs of people living in poverty. Originally seeded by USAID, the Development Engineering field is growing. During the 2018-2019 academic year,18 additional students enrolled in the program representing a growth of more than 160 percent from the previous year. They include nine students from the College of Engineering, six students from the College of Natural Resources, two from the College of Environmental Design, and one from the School of Education. Beyond this disciplinary heterogeneity, the program attracts a diverse pool of students: 50 percent of the incoming cohort are women and 25 percent are underrepresented minorities.

Now in its fifth year, the Development Engineering program is producing a wide range of scholarship and its graduates have gone on to positions in academia, industry, the nonprofit sector, and their own enterprises. Below are summaries of recent graduates’ dissertation research.

Inspecting What You Expect: Applying Modern Tools and Techniques to Evaluate the Effectiveness of Household Energy Interventions (2016)

Author: Ajay Pillarisetti, Postdoctoral Researcher at UC Berkeley

Advisor: Kirk R. Smith, Professor of Global Environmental Health

Many low-income families in North India rely on solid fuel use for household cooking, heating, and lighting. Use of these fuel sources result in exposure to fine particles (called PM 2.5) and is one of the leading causes of ill health globally (approximately 4 million premature deaths). This dissertation examines the rollout of PM sensors in these environments, the deployment of 200 advanced cookstoves to pregnant women in India, and examines the adoption rates of various cookstoves in rural districts.

Quantifying the Crisis of Cooking: Next Generation Monitoring and Evaluation of a Global Health and Environmental Disaster (2016)

Author: Daniel Wilson, CEO, Geocene: Sensors and Analytics Connected

Advisor: Ashok Gadgil, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Since the beginning of the modern Darfur conflict in 2003, violence has forced Darfuri families from their homes.The impetus for the Berkeley-Darfur Stove (BDS) is to reduce the burden and danger IDP women face when acquiring fuel in and around the camps. The BDS’s improved thermal efficiency allows women to cook food using less fuel than a traditional three-stone fire.

In the Global South, cooking stoves’ contribution to human disease is comparable to dirty water and is responsible for more annual deaths than AIDS, malaria, and tuberculosis combined. While biomass-burning stoves generate over 1 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide annually, the shipping of resources to communities often increases carbon dioxide use. Though estimating carbon dioxide use is often a flawed science, quantifying this ecological and health problem is a first step to addressing the solutions.

Health, Human Capital, and Behavior Change: Essays in Development Microeconomics (2016)

Author: Angeli Kirk, Affordable Internet Research Manager at Facebook

Advisor: Elisabeth Sadoulet, Professor of Agricultural and Resource Economics

This dissertation combines three empirical studies of household behaviors as they relate to investment in health and human capital in developing countries. The first explores how changes in children’s nutrition in Uganda correspond to household income. The second studies measurement activities in a cookstove intervention in Darfur, Sudan, with insights into what may be missed in traditional evaluation approaches as well as how technology adoption may benefit from an unintended “nudge.” The third evaluates the impacts of a conditional cash transfer program in El Salvador, with a focus on how program compliance and benefits change time allocations among household members.

Case Studies of IDEO.org and the International Development Design Summit (2016)

Author: Jessica Vechakul, Designer and Social Innovation Strategist

Advisor: Alice Agogino, Professor of Mechanical Engineering

In the social sector, programs often fail due to a lack of understanding of the norms, knowledge, and needs of the people who execute and benefit from the solutions offered by those programs. Human-Centered Design (HCD) offers a broadly-applicable problem-solving framework and methods for developing an in-depth understanding of people who are directly impacted by development challenges, generating creative ideas, and rapidly learning from small-scale pilots. This dissertation characterizes two drastically different approaches for teaching and practicing HCD for Social Impact: that of IDEO, a company that pioneered the HCD approach, and that of the International Development Design Summit program, in which students and members of low-income communities learn to design appropriate technologies and launch social enterprises.

Effects of Air Flow Modifications on Biomass Cookstoves (2016)

Author: Kathleen Lask

Advisor: Ashok Gadgil, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Since biomass cookstoves use wood, charcoal, crop residues, and/or animal dung as fuel, emissions from cooking lead to possibly fatal health effects. When researching the effects of the Berkeley-Darfur cookstove, a design said to pollute less, measurement sensors are often designated far away from the source, which miss the cookstove’s combustion efficiency. This dissertation focuses on the pollutant production, measured by the opacity or soot volume fraction of both the Berkeley-Darfur and conventional cookstoves to paint a more detailed comparison between the two.

Designing and Evaluating Novel Approaches to Nitrogen Recovery from Source-Separated Urine (2017)

Author: William Tarpeh, Assistant Professor of Chemical Engineering, Stanford University

Advisor: Kara Nelson, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Cattle breeding is a major contributor to greenhouse emissions, using about 30 percent of the Earth’s land surface and producing about 70-120 kg of methane per cow. Recovering nitrogen from collected urine can reduce the costs and environmental impact of mass animal raising. Focusing on how to strip nitrogen with 93 percent efficiency, this dissertation examines a new approach that holds promise for creating greener agriculture.

Harmonizing Technological Innovation and End-of-Life Strategy in the Lighting Industry (2017)

Author: Rachel Dzombak, Blum Center Researcher and Lecturer

Advisor: Arpad Horvath, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Sara Beckman, Professor Haas School of Business

Climate change and a growing global population are placing considerable constraints on material, water, and energy resources. Tracking the product life of LEDs may provide insights as to how products are managed throughout the lifecycle as well as their end-of-life fate. Primarily, this dissertation examines current end-of-life strategies, how various design choices and failure modes influence a product’s options at end of life, and how economic costs and environmental impacts vary among end-of-life strategies.

Designing a Scalable and Affordable Fluoride Removal (SAFR) Process for Groundwater Remediation in India (2017)

Author: Katya Cherukumilli, CEO, Co-founder, and Technical Lead, Global Water Labs and University of Washington Commercialization Fellow

Advisor: Ashok Gadgil, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering

Globally, 200 million people are at risk of adverse health effects from drinking groundwater contaminated with geogenic fluoride concentrations exceeding the World Health Organization’s maximum contaminant limit. Although many defluoridation technologies have been demonstrated to work in lab, most have proven inappropriate for developing countries because they are cost-prohibitive, require skilled labor, or are difficult to scale. Activated alumina (AA) column filters are widely used by the upper middle class but production of AA remains costly in terms of money, energy, and greenhouse gas emissions. Eliminating these energy-intensive steps in refining bauxite, a ubiquitous aluminum-rich ore ($30/tonne), to AA ($1,500- $2,000/tonne), has the potential to reduce the annual per-capita material cost of treated water significantly. The purpose of this dissertation is to ascertain the use of bauxite as a potentially inexpensive defluoridation technology through experimental studies characterizing globally diverse bauxite ores and tradeoffs associated with mild processing steps to enhance fluoride removal performance.

Demand-side Knowledge for Sustainable Decarbonization in Resource Constrained Environments: Applied Research at the Intersection of Behavior, Data-Mining, and Technology (2017)

Author: Diego Ponce de Leon Barido, founder of Three Stone Analytics

Advisors: Daniel M. Kammen, Duncan Callaway, and Alexey Pozdnukhov

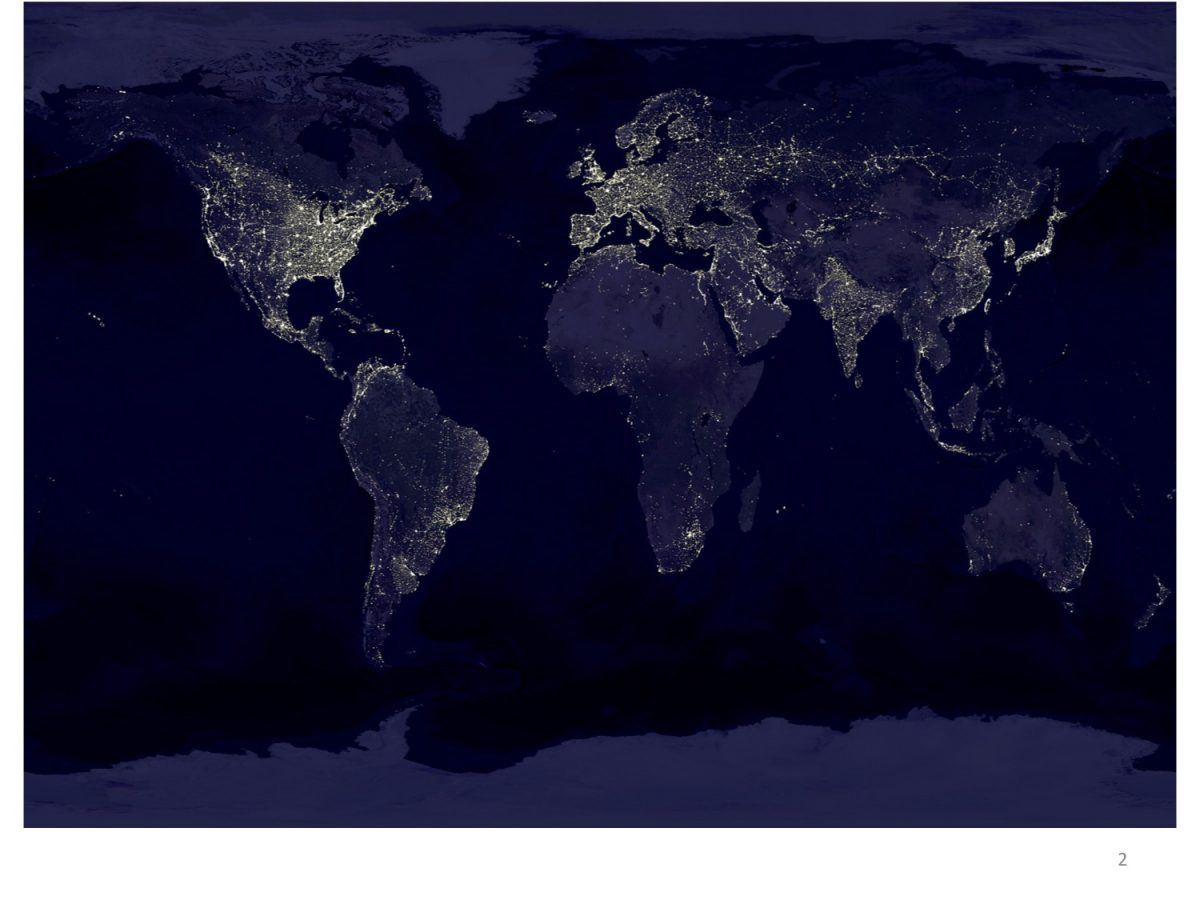

The global carbon emissions budget over the next decades depends critically on the choices made by fast growing emerging economies. However, few studies exist that develop country-specific energy system integration insights that can inform emerging economies in this decision-making process. High spatial- and temporal-resolution power system planning is central to evaluating decarbonization scenarios, but obtaining the required data and models can be cost prohibitive, especially for researchers in low, lower-middle income economies. Among other things, this dissertation investigates the role and importance of high-resolution open access data and modeling platforms to evaluate fuel- switching strategies. Oil price sensitivity scenarios suggest renewable energy to be a more cost-effective long-term investment than fuel oil, even under the assumption of prevailing cheap oil prices.

Elucidating Liver Fluke Transmission Dynamics: Synthesizing Lab, Field, and Modeling Methods (2018)

Author: Tomas Leon, Postdoctoral Researcher at UC Berkeley School of Public Health

Advisor: Robert C. Spear, Department of Environmental Health Sciences

In northeast Thailand, infection with the Southeast Asian liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini is a public health priority, infecting over 50 percent of the population in some villages and causing 5,000 excess cancer cases per year. People acquire the parasite by eating raw or undercooked fish, a deeply embedded local cultural and culinary tradition. Health education is essential to preventing and controlling the disease, but the environment also plays a major role in enabling and catalyzing transmission between hosts. An emphasis on disease ecology and the environmental determinants of transmission is useful and necessary for public health understanding and for informing and designing future treatment and control interventions. This dissertation takes that approach, investigating each disease host and linkage for the role of the environment in influencing transmission.

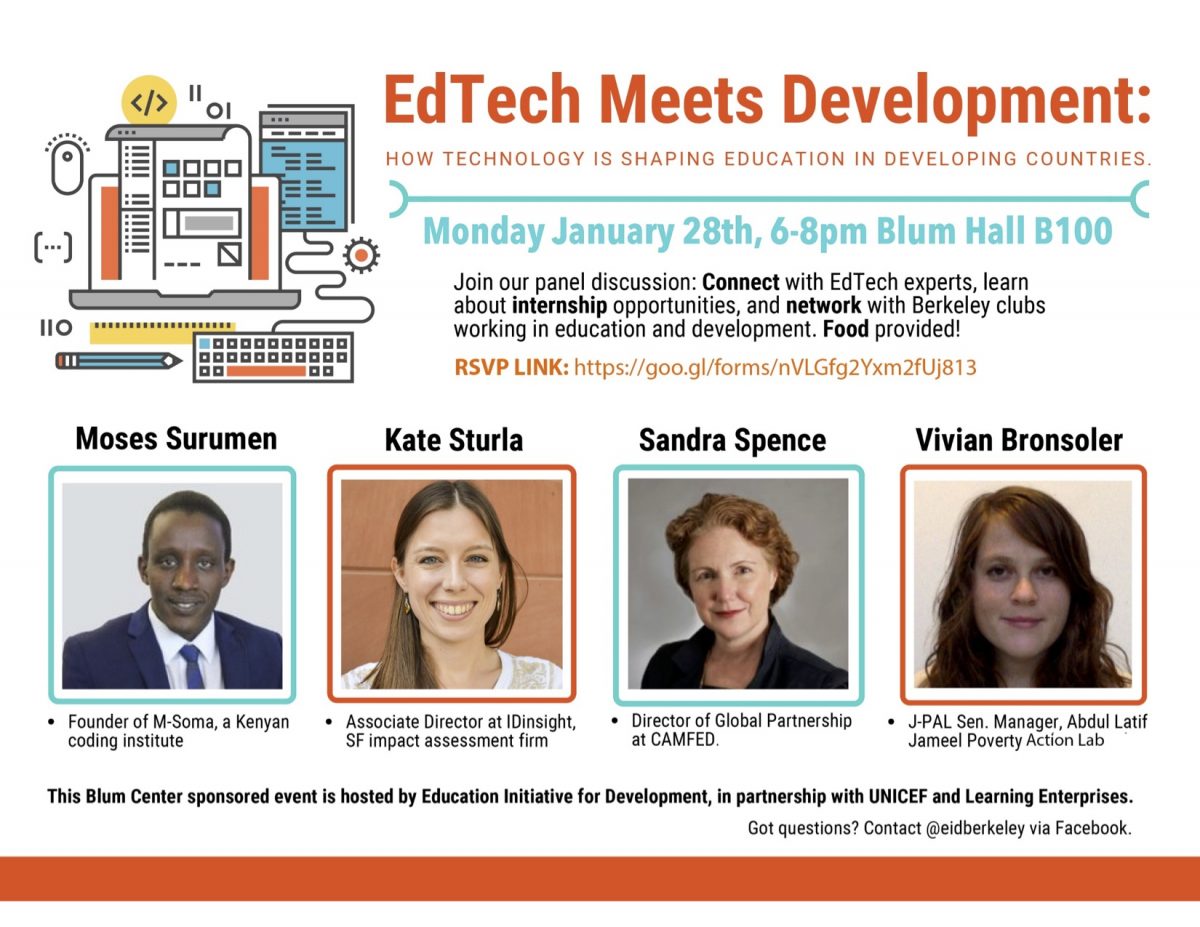

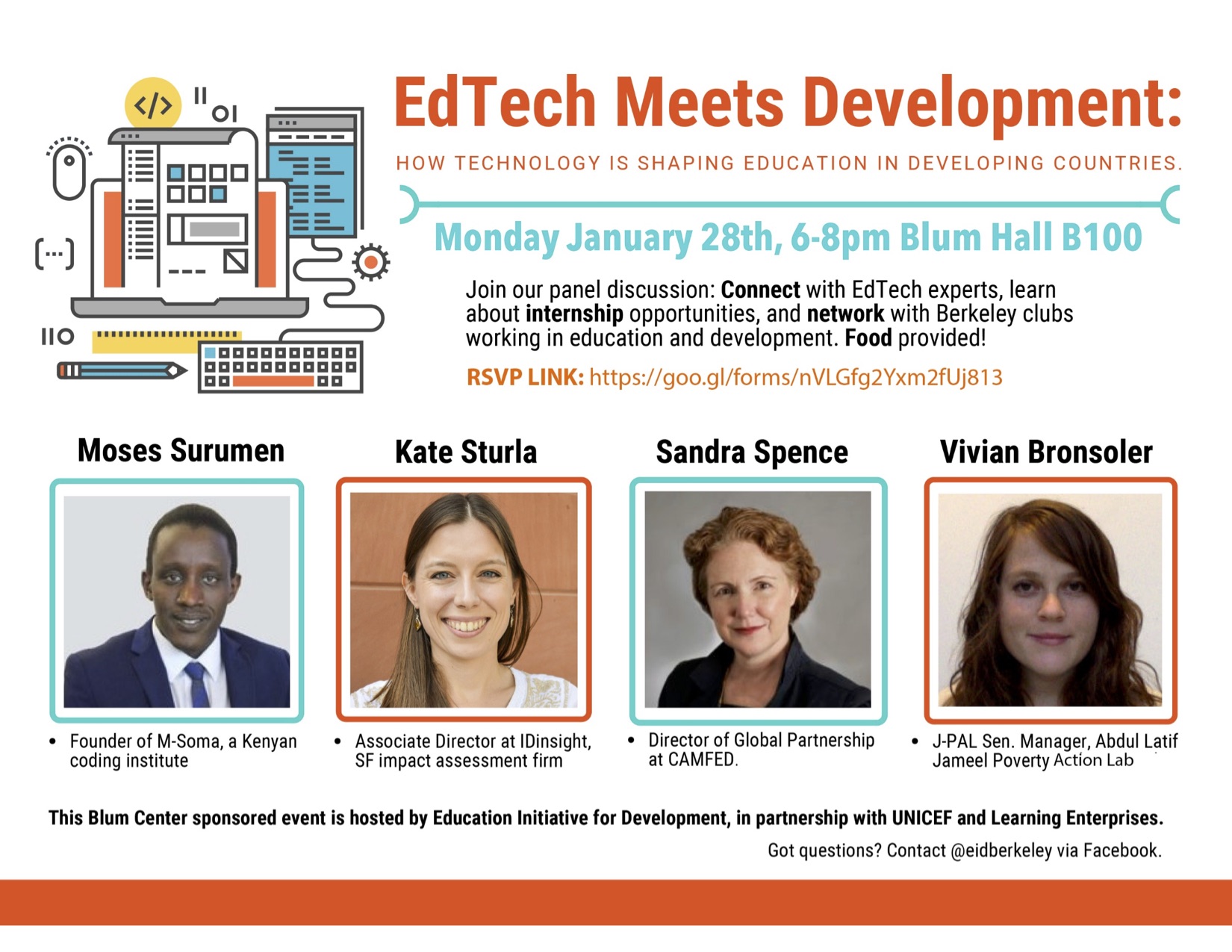

Education has long been considered a means to move out of poverty. Edtech—teaching and learning that makes use of technology—has in recent years become a

Education has long been considered a means to move out of poverty. Edtech—teaching and learning that makes use of technology—has in recent years become a

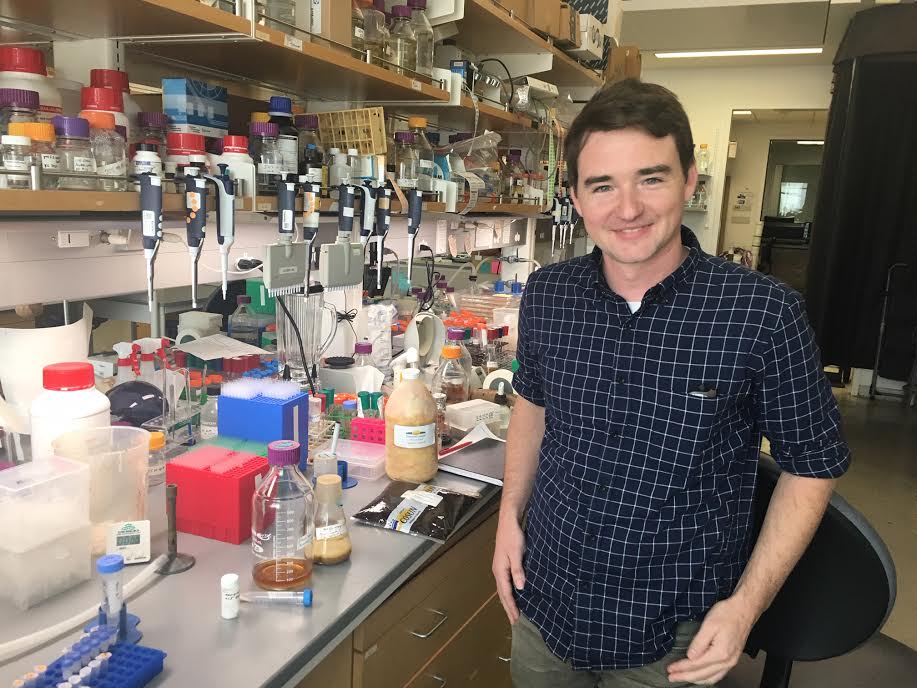

Early in 2017, Ryan Protzko, then a doctoral student in biochemistry at UC Berkeley, was working on research to turn orange peels into eco-friendly bottles and contacted a citrus juicer in California’s Central Valley. Would the company be able to spare some orange peels? Yes, responded the representative, the juicer could truck “a couple tons” of wet navel peel to Protzko’s lab free of charge.

Early in 2017, Ryan Protzko, then a doctoral student in biochemistry at UC Berkeley, was working on research to turn orange peels into eco-friendly bottles and contacted a citrus juicer in California’s Central Valley. Would the company be able to spare some orange peels? Yes, responded the representative, the juicer could truck “a couple tons” of wet navel peel to Protzko’s lab free of charge.

At the 2018 Autodesk University conference, a weeklong event bringing together representatives from the building, design, manufacturing, and construction industries, the skillsets required for the future workforce were a heavy focus. In her keynote speech, Beth Comstock, the former CEO of GE, discussed how multinational companies are reorganizing around digital information flows, asserting, “We can’t control change, we can’t predict the future, but we can be more adaptable.”

At the 2018 Autodesk University conference, a weeklong event bringing together representatives from the building, design, manufacturing, and construction industries, the skillsets required for the future workforce were a heavy focus. In her keynote speech, Beth Comstock, the former CEO of GE, discussed how multinational companies are reorganizing around digital information flows, asserting, “We can’t control change, we can’t predict the future, but we can be more adaptable.”

The UC system is often lauded for its ability to cultivate socioeconomic mobility. A

The UC system is often lauded for its ability to cultivate socioeconomic mobility. A

Daniel Kammen asserts that everything he has learned about communicating scientific research to a lay audience has been “by accident.” Yet Kammen, chair of the Energy and Resources Group at UC Berkeley who also holds parallel appointments in the Goldman School of Public Policy and the Department of Nuclear Engineering—is for all intents and purposes a master communicator to the press, government, and non-scientists in general.

Daniel Kammen asserts that everything he has learned about communicating scientific research to a lay audience has been “by accident.” Yet Kammen, chair of the Energy and Resources Group at UC Berkeley who also holds parallel appointments in the Goldman School of Public Policy and the Department of Nuclear Engineering—is for all intents and purposes a master communicator to the press, government, and non-scientists in general.