Teachers as Agents of Conflict Resolution in Chile: Big Ideas Winners Kuy Kuitin

Category: News

Founders of Endaga to Join Facebook

Hygiene Heroes: UC Berkeley Team Promotes Hand-Washing Curriculum to Combat Preventable Diseases

By Carlo David

A group of students, led by Professor David Levine of UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business, are seeking to combat preventable diseases in developing countries like Bolivia, Cambodia, Tanzania and India, where significant populations do not have access to clean water and soap. Their goal is to make hand washing routine for thousands of students and teachers by introducing a fun and interactive curriculum—called “Hygiene Heroes”—at public schools. The Hygiene Heroes curriculum includes recreational activities, board games, and a book, as well as cost-efficient supplies like “soapy bottles.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1.8 million children under the age of 5 die annually from diarrheal diseases or pneumonia, the top two causes of deaths among young people. The alarming rate of children dying from such preventable diseases prompted Prof. Levine, along with several students, such as Nimerta Sandhu (Haas ’14) and Melanie Cernak (Haas ’15), to undertake this project.

Hygiene Heroes was piloted in Cambodia and Tanzania in the summer of 2013. During the academic year, the team conducted extensive outreach to school districts, principals, and community organizations to test the project’s curriculum. Meanwhile, over the summers of 2013 and 2014 under the leadership of Gautam Srikanth, a Cal undergraduate student in Environmental Economics, several UC Berkeley students traveled abroad to lay the groundwork for expanding the project in Chennai, India.

Prof. Levine explained there are many economic and cultural misconceptions about why people do not develop a hand washing habit. According to a recent World Health Organization and UNICEF report covering 54 middle- and low-income countries, 35 percent of health facilities do not have water and soap for hand washing.

“Lots of people rinse hands with water. The Hygiene Heroes project is targeting people who do not wash their hands with soap,” said Levine. “Even here in the United States, when no one is looking, people tend to not wash their hands with soap.”

Continued Levine: “We introduced soapy bottles, which are basically empty water bottles filled with water and soap. With them, classrooms can create routines, such as squeezing soapy water on each student’s hands as they leave for lunch and head to a faucet to rinse. Such routines constantly reinforce students’ hand washing.”

Hygiene Heroes is working on a shoestring budget with funding from online donors, the Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA), and the Haas School of Business, and is facing equally limited financial resources from the schools that the project is targeting. To deal with these challenges, the team is capitalizing on previous efforts launched in India to promote hand washing.

“We are building on previous curricular efforts,” said Levine. “Part of the task is to reinvent some of the approaches used to promote hand washing with soap.” In the past, said Levine, glitter has been used in games to demonstrate the necessity for children to wash their hands after they play and especially before eating. But glitter is expensive, so scaling such an approach is difficult. Instead, the Hygiene Heroes team is using cost-efficient alternatives, such as chalk dust or even turmeric, to play the “pass the germ (and be aware)” game.

From his time as a senior economist on President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisors to his present position as the Eugene E. and Catherine M. Trefethen Chair in Business Administration at UC Berkeley, Levine has analyzed the impacts of investing in health and education, especially in poor nations. He is currently one of 19 Cal faculty members behind a new program called Development Engineering for graduate students pursuing research in poverty alleviation.

In the case of this project, said Levine, “One of the challenges is to work with regular teachers, who are busy, and make our proposed curriculum part of their routine. The board game [we introduced in Cambodia] is popular among kids, but because it is not part of their curriculum, it can serve only as supplementary material.”

The Hygiene Heroes team has been working across disciplines to find collaborators. Jacqueline Zhou, from UC Berkeley’s Art Department, for example, is the illustrator of the children’s book King Akbar Writes a Law. In the story, Prime Minister Birbal, a popular folk tale character in much of South Asia, requires the palace’s servants to wash their hands with water and soap. The prime minister must convince the king of the importance of the new law, slowly helping the monarch realize that contamination can spread, even if it cannot be seen.

Culture is an important facet of Hygiene Heroes. Nimerta Sandhu, who first joined the initiative in January 2013 and now works as a management consultant in the health industries, found her passion for public health and community service to be a guiding force for her involvement with the project. “Working with underserved and minority communities, the project has been very important to me. I hope to continue these efforts both internationally and within the United States,” she said.

For Melanie Cernak, who now works as a business development associate at a Silicon Valley firm, her first-hand interaction with the children and their enthusiastic reception of her was fascinating, although sometimes uncomfortable. “Students were attentive and largely would listen to me,” she said. “They wanted to wash their hands because they saw Americans washing their hands. But that is not a sustainable model.”

Over the past two years, the project has established important connections inside and outside of Chennai. The Indian Institute of Technology in Madras (IIT-Madras) played a pivotal role in testing Hygiene Heroes in the region, and in searching for schools that benefit from the project. Currently, the team—with more than a dozen students involved—has partnered with Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan (SSA), a government program that is responsible for 30,000 schools under India’s Department of School Education and Literacy. Hygiene Heroes is also hoping to increase its outreach through Teach for India, an Indian adaptation of Teach for America, and CLEAN India, a national campaign advocating for clean, healthy, and sustainable lifestyle.

Although the Hygiene Heroes team is aiming to create long-lasting behavioral change, it does not expect to produce far-reaching results instantly. A project of this scale requires constant engagement and understanding of behavioral and political factors. “It will take a long time,” Prof. Levine said. “But it is the most important solvable problem on the planet.”

GPP Interim Director Clare Talwalker Reflects on Katherine Boo’s Visit to Berkeley

Big Ideas Winners Aim to Digitally Track Vaccinations in Rural India

Blum Center Fosters a New Kind of Development Professional: The Development Engineer (DevEx News)

https://www.devex.com/news/a-new-kind-of-development-professional-the-development-engineer-86919

We Care Solar is awarded US$1 million United Nations Energy Grant to expand the use of life-saving “Solar Suitcase” (United Nations News)

https://poweringthefuture.un.org/news/awardceremony2015

Blum Center-Supported We Care Solar Wins $1 Million UN Award

We Care Solar, the Blum Center-supported nonprofit, has won the United Nations’ first “Powering the Future We Want: Recognizing Innovative Practices in Energy for Sustainable Development” award. We Care Solar is being recognized with this $1 million grant for its pioneering work providing sustainable energy to improve maternal and child health. The nonprofit produces Solar Suitcases, which provide light and energy to under-resourced medical facilities, primarily in Africa and Asia.

The award is the first by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs and signals the convergence of efforts around global health, renewable energy, and sustainable development. It comes on the eve of the UN’s historic adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals.

Laura E. Stachel, We Care Solar co-founder and executive director, accepted the award at a September 14, 2015 ceremony at the United Nations introduced by Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. From over 200 applicants, We Care Solar was one of 12 finalists invited to the United Nations to share sustainable energy practices.

Stachel, an obstetrician, conceived her innovation in 2008 while conducting public health research in Nigeria. She was one of the first experts to recognize the link between maternal mortality and lack of access to reliable electricity. To address this need, she and her husband, Hal Aronson, co-founded We Care Solar in 2010. Together, they developed compact portable Solar Suitcases to provide essential lighting and electricity to maternal health centers. To date, 1,300 We Care Solar Suitcases have been distributed to health centers—and that number is expected to double in the next twelve months.

Stachel said: “The United Nations is shining a light on an area that has all too often been overlooked—the lack of reliable electricity in health facilities. I have had the privilege of working with hundreds of health workers who have seen the miracle of light and power in saving lives, and we have much more work to do. This award is the beginning of a brighter future for women everywhere.”

Stachel used her acceptance speech to declare a commitment to light up and power every primary health clinic in the world with renewable forms of energy. Today, as many as 300,000 health centers worldwide lack reliable power. “There can no longer be silos between global health goals and sustainable energy goals. The time has come to collectively work together to give every health care worker the power they need to save lives,” Stachel said.

The Problem with “Help” in Global Development (Commentary by DevEng student Julia Kramer in the Stanford Social Innovation Review)

http://ssir.org/articles/entry/the_problem_with_help_in_global_development

Berkeley Lab Water Technology Boomerangs from Bangladesh to California

By Tamara Straus

In 2006, when UC Berkeley Civil Engineering Professor Ashok Gadgil began researching the possibility of removing arsenic from drinking water using electrochemistry, he targeted his invention at South Asia, specifically Bangladesh and West Bengal, where more than 60 million people are estimated to be consuming groundwater with dangerously high arsenic levels.

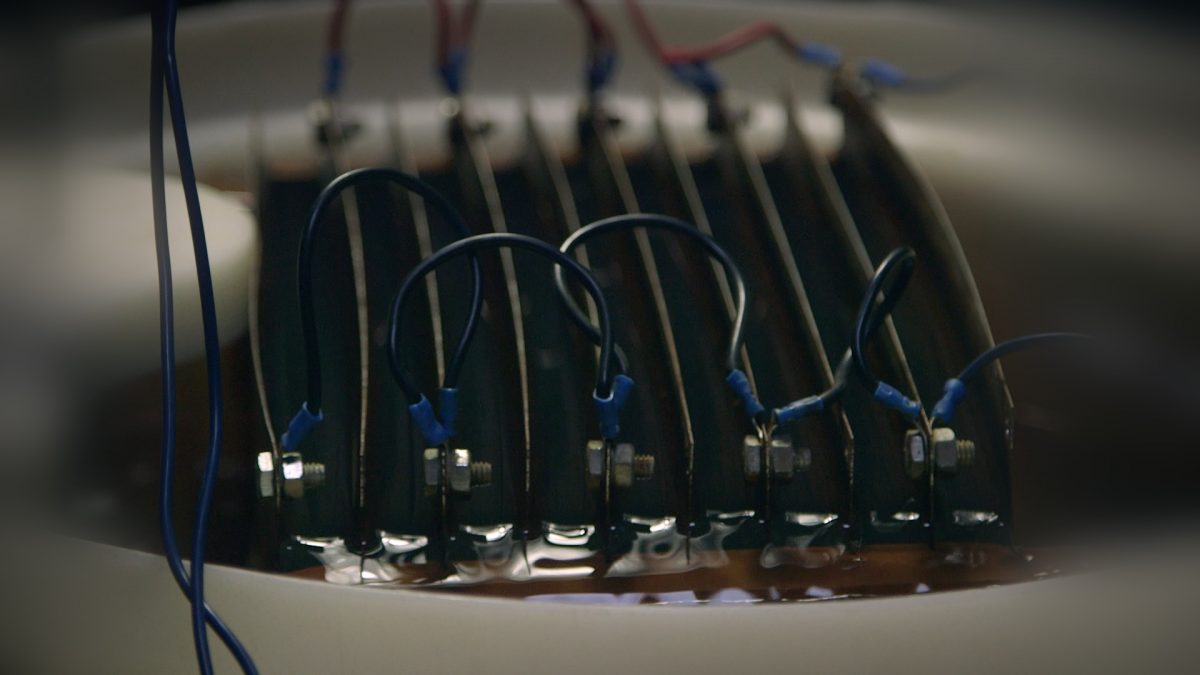

Gadgil’s invention, ECAR (short for Electrochemical Arsenic Remediation) has since been tested in his lab and is currently being implemented in the field, thanks to funding from the Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and the Development Impact Lab. Since December 2013, the technology has been under license by the Indian company Luminous Water Technologies, which plans to bring ECAR to arsenic-affected villages throughout India and Bangladesh. Meanwhile, members of the ECAR team, lead by Gadgil and Susan Amrose are conducting a 10,000 liter-per-day trial of the system in preparation for the considerable scaling.

For Gadgil and Amrose, these outcomes are the result of years of experimenting, planning, and partnering. One outcome they didn’t necessarily expect, however, is unfolding here in the United States. During the summer of 2013, Amrose and John Pujol launched their own company, SimpleWater, using the same electrochemical arsenic remediation technology developed in Gadgil’s lab but directed at the tens of thousands of wells and rural American water systems with high levels of arsenic. With funding from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, SimpleWater successfully validated the technology in California in 2014 and is now preparing a larger scale pilot in Grimes, California. ECAR was also awarded a 2013 UC Proof of Concept Program Commercialization Gap Grant, to see if it could be used to remediate arsenic-contaminated groundwater in California.

This turn of events is a prime example of what business and engineering scholars are calling “reverse” or “boomerang” innovations—whereby products and services developed as inexpensive models to meet the needs of developing nations are then repackaged or remodeled as low-cost alternatives for developed markets. In the case of Grimes, a town of about 550 people 50 miles north of Sacramento, ECAR technology may prove as useful to residents as those in rural Bangladesh—although the regulatory, political, and environmental conditions are quite different.

Amrose explains that the water treatment needs of remote, low-income, and small American communities have largely been ignored, because U.S. innovation focuses so much on large municipal systems. “ECAR technology was designed to be affordable and robust in rural and primarily very low-income South Asian communities,” she said, “which translates easily to the unmet U.S. needs that SimpleWater is addressing.”

One reason that arsenic-contaminated water has been overlooked globally is that it is hard to detect. Arsenic dissolves from soil and rock into drinking water supplies and is tasteless and odorless, but it unquestionably a poison. Over the past few decades, scientists have found increasing evidence that chronic ingestion of arsenic results in lower IQ in children as well as severe maladies, such as lesions, diabetes, cancer, and blood vessel diseases that can lead to gangrene, amputation, and premature death. As a result, in 2001-2002 the World Health Organization and the Environmental Protection Agency set a new drinking water standard prohibiting the consumption of water with more than 10 parts per billion (ppb) of arsenic. Yet arsenic in drinking water has remained an international problem for which long-term solutions have been elusive.

As Gadgil told Lawrence Berkeley Lab News in a 2014 article, “A lot of technologies to remove arsenic on the community- and household- scale have been donated. But if you go to these villages it’s like a technology graveyard. One study found that more than 90 percent failed within six months, and then were abandoned to rust in the field.”

Among the reasons Gadgil thinks ECAR could prove effective is that the technology has been created to be inexpensive and easy to maintain. Unlike complex chemical processes or maintenance-heavy devices, ECAR works by using electricity to quickly dissolve iron in water. This forms a type of rust that binds to arsenic—and that can then be separated from the water through filtration or settling. ECAR is not meant to serve large populations that are serviced by government water systems. Instead, the technology is designed for residents who can collectively maintain and own a water system.

One of the goals of SimpleWater’s ArsenicVolt system is to provide remote monitoring of arsenic levels. This is being done, said CEO Pujol, for a very simple reason: There are few water engineers in the U.S. with expertise in arsenic or other heavy metals—and even fewer who will live in a small town. Indeed, lack of detection of arsenic is one of the biggest problems facing small system U.S. water supplies. According to data collected over the past four decades by the U.S. Geological Survey, for example, 25 percent of public groundwater supply sources in parts of California’s Central Valley of exceed 10ppb of arsenic, which became the federal standard in 2008.

Pujol points out that the burden of arsenic is disproportionately falling on minorities and residents of lower socioeconomic status. A 2012 study of community water systems in the San Joaquin valley showed that minorities and low-income residents have higher levels of arsenic in their drinking water and higher levels of non-compliance with drinking water standards. Those communities, said Pujol, are likely to be overlooked by new technologies.

“Innovation in the drinking water treatment industry, of which there hasn’t been a lot, has focused on the big profit centers, which are big water systems in LA, Chicago, San Francisco, and so on,” said Pujol. “The smaller places have been left in the dust; they can’t afford to buy those technologies at smaller scales.”

Pujol said SimpleWater identified Grimes as the pilot location because it is small and low-income, but also because it has a persistent arsenic problem. Grimes’ water management system is also run by Stuart Angerer, who works as the environmental monitoring section chief at the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in Yuba City and is deeply interested in technological innovation. Angerer explained that previous attempts to remove arsenic from Grimes’ drinking water were inadequate, and building a treatment plant would be too expensive.

Yet Angerer noted, “The big thing for SimpleWater will be getting California approval from the State Water Resource Control Board. There’s going to be a lot of scrutiny and tests, but I am hopeful because we need innovative approaches that are simple and save us money.”

Pujol is currently installing an ArsenicVolt in Grimes in preparation for a six-month test. He said if the ArsenicVolt gets government approval, SimpleWater does not plan to directly sell its invention. Rather, it would look for a large water treatment systems company to acquire the technology and add it to its portfolio of solutions.

“This was about going after a solution to a really gnarly problem—dangerous levels of arsenic in drinking water—and coming back with a reliable innovation that can been tested and implemented in a more rigorous regulatory environment,” said Pujol. “I believe electrochemistry can transform the way water is treated in small communities, whether in a small town in India or California.”

The Berkeley Difference: Katya Cherukumilli’s Path to Problem Solving

By Sean Burns

Katya Cherukumilli arrived at Cal with a calling. Having spent the first seven years of her life in the southeastern coastal state of Andhra Pradesh, Cherukumilli emphasizes, “The problem of people not being able to meet their most basic needs has always been close to my heart.” During her undergraduate years at Cal (2008-2012) as Regents’ and Chancellors’ Scholar, she majored in Environmental Sciences and minored in Global Poverty & Practice and Energy & Resources. The impacts of climate change were central to her studies and, overtime, water and sanitation challenges in developing regions became the focus of her work.

During her junior and senior year, Cherukumilli sought out a wide range of research opportunities in these fields. She worked at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory, researching the impact of climate change on plant species distribution in collaboration with Professor John Harte (ESPM). Under the supervision of Professor Kara Nelson (CEE), Cherukumilli then fulfilled the “practice” component of her minor in Global Poverty through field analysis of the risks associated with water irrigation along the vegetable supply chain in the Indian city of Dharwad, Karnataka. Her concerns were as much with microbes as with social processes—“I asked myself, where is knowledge about how vegetables are irrigated lost from farm to consumption?”

Her undergraduate years culminated with participation in the Haas Scholars program. Selected among one of 20 seniors, Cherukumilli developed her climate change research with Professor Harte into a senior thesis. She describes the interdisciplinary cohort of peers and mentors as “incredible and transformative.” No other setting at Cal had offered her a context where she could expose her ideas, methods, and questions to a group of dedicated people with such a wide range of growing expertise. As she honed her research on ecological responses to climate change, her fellow Haas Scholars worked on issues of immigration law, gender equity, mental health challenges for veterans, and more. The weekly dialogues were rigorous and mind-opening. “You just don’t see this kind of interdepartmental collaboration enough here,” says Cherukumilli.

This point of interdisciplinary collaboration for social progress gets at the heart of what Cherukumilli sees as Berkeley’s greatest educational promise—what many call “the Berkeley difference.” When she made the choice to pursue her doctorate here in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, she knew she had to find pockets at Cal that fostered interdisciplinarity and real-world problem solving. One place she found this intersection was at the Blum Center for Developing Economies. Cherukumilli’s first exposure to the Blum Center was through the Global Poverty & Practice minor. She met her current doctoral advisor, Professor Ashok Gadgil, when he spoke about his work on the Darfur Cook Stove Project for the Blum Center course “Global Poverty: Hopes and Challenges in the New Millennium” (GPP 115).

As a doctoral student in Gadgil’s Lab, Cherukumilli notes that two Blum Center affiliated programs are giving her a chance to amplify the impact of her research. During the spring of 2015, Cherukumilli teamed up with four other Cal graduate students to earn second place in the global health category of the annual Big Ideas@Berkeley competition. Their winning idea emanates from Cherukumilli’s doctoral research; the team is setting out to develop a bauxite-based defluoridation technique for communities whose water source has dangerously high levels of fluoride. The impacts could be massive. According to the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology, approximately 200 million people are regularly consuming water with levels of fluoride that dangerously exceed World Health Organization standards (1.5 mg/L (ppm)). Fluoride naturally occurs in many aquifers, but exposure to high fluoride levels can cause detrimental health effects, including anemia and skeletal fluorosis. While de-fluoridation techniques already exist on the market, Cherukumilli’s team aims to significantly reduce the cost and environmental impact of current processes. In July 2015, the project got additional recognition when it earned first place in UC Irvine’s Designing Solutions for Poverty Contest.

Cherukumilli is quick to note that the strength of her defluoridation project resides in the interdisciplinary character of her team. Her partners at Cal include a political science doctoral student and three MBAs—one of whom is also pursuing a public health degree. Cherukumilli notes that Big Ideas created a structured and incentivized forum through which they could apply their shared interests and build upon their diverse skills. While her focus is on technical design, her team members are conducting partnership development, field-testing, marketing, fundraising, and evaluation.

Cherukumilli says she yearns for there to be more curricular and co-curricular spaces at Cal where students—undergraduate and graduate alike—can come together to research and directly engage with pressing social problems. She’s found one such place in the newly launched “designated emphasis” in Development Engineering (Dev Eng) for graduate students. The Dev Eng program, which launched in fall 2014, provides course work, research mentoring, and professional development to students seeking to develop, pilot, and evaluate technological interventions for improving life in low-income settings. Cherukumilli is part of the inaugural cohort of students and faculty forging this emergent discipline. The core course, Dev Eng C200, is taught by Professors Alice Agogino (Mech Eng) and David Levine (Haas Business) and draws students from computer science, public health, city and regional planning, economics, information studies, and more.

For Cherukumilli, the Dev Eng context is ideal because, “confronting these problems from the technical side, I’ve already come to understand how deeply interdisclipinary they are—issues of local context, people, politics, and education. Dev Eng structures a space where this complexity can be explored.”

During the summer of 2015, Cherukumilli was busy in the lab, advancing her research on bauxite. In the years ahead, as she completes her Ph.D., she will look to continue her work at a national lab, in a university context, or in the nonprofit sector. Wherever she ends up, it’s clear she’ll carry with her the Berkeley difference—the rigorous analytic capacity to see the complexity of daunting social problems and have the resolve to implement possible solutions.

Ticora Jones: The Federal Government Scientist for Global Development

http://dil.berkeley.edu/ticora-jones-the-federal-governments-scientist-for-global-development/

GridWatch: Using Cell Phone Sensors to Detect Power Outages

Big Ideas@Berkeley Winners Visualize an End to Cervical Cancer

By Carlo David

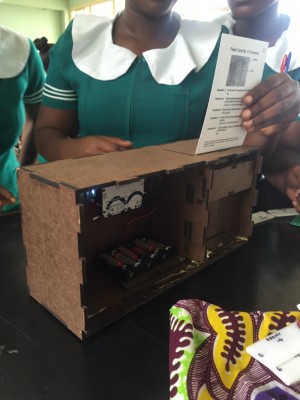

Prompted by funding and recognition from the Big Ideas@Berkeley contest, a group of Cal students headed by Mechanical Engineering graduate student Julia Kramer is seeking to establish a sustainable training program called “Visualize” for midwives in Ghana. In a country where only five percent of women have been screened for cervical cancer, Visualize aims to create a system in which midwives receive the essential skills and tools to perform a visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (vinegar). The inspection method, known as VIA, is a low-cost and effective way to screen for cervical cancer, but it is not widely used in Ghana and other countries due to a lack of training and awareness.

Kramer and Maria Young first conceived of the project as undergraduates at the University of Michigan. “We were part of a group of five engineering students who spent eight weeks in Ghana for a cultural immersion and design ethnography experience,” said Kramer.

At Michigan, she and her collaborators developed the first few prototypes of a VIA training simulator, based on design requirements they developed at two major teaching hospitals in Ghana. At Berkeley, Kramer teamed up with fellow Mechanical Engineering and Haas School of Business students Abhimanyu Ray, Karan Patel, and Betsy McCormick, to develop the midwife VIA training concept. Visualize’s faculty advisors include public health professional Kyle Fliflet and Mechanical Engineering Professor Alice Agogino, who is chair of the Development Engineering graduate group.

Kramer explains that her project was motivated largely by interactions with midwives, nurses, and doctors in Ghana, along with substantial data supporting the need for more cervical cancer screening. Annually and worldwide, 275,000 women die from cervical cancer. Eighty percent of deaths occur in developing countries, which often do not have the medical infrastructure to diagnose and treat cervical cancer. VIA has been proven to serve as a low-cost alternative to methods like the Pap smear. A 2008 International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics study found that VIA could reduce mortality rates by 68 percent. Through midwife-administered VIA tests and subsequent treatments, the Visualize team estimates it can avert 150,000 deaths per year.

Based on their experiences in Ghana, Kramer and her colleagues believe midwives, rather than doctors or other medical professionals, are the best means to implement their public health solution. “Midwives have and can be trained for this procedure,” said Agogino. “As a matter of fact, because such an intimate procedure requires interpersonal communication skills, midwives are better suited than licensed medical doctors.”

The VIA method is not only cheaper than a Pap smear—if properly performed, it also can be equally effective. The method works as follows: a midwife performs a preliminary pelvic examination; she inspects any pre-existing abnormalities; she applies a small amount of table vinegar in the cervix; if acetowhite lesions appear, cancerous cells may be at work.

If there are signs of pre-cancerous cells, the midwife may perform cryotherapy, a procedure that freezes off cervical abnormalities and eradicates cancer cells. In a 15-year controlled trial of 151,000 women ages 35-64 in Mumbai, India, the mortality rate in the cryotherapy treatment group was reduced by 31 percent.

There are, however, unique challenges and financial hurdles to implementing Visualize. According to Agogino, “One of the biggest challenges is identifying infrastructures that already exist for training midwives, so the midwives can eventually train other women in Ghana.” Indeed, the Visualize team is exploring whether it is viable to incentivize women to recruit and train other women, particularly to reach remote areas.

Communication may also be a challenge for Kramer and her team. “There’s an ever-present challenge of working in a culture I’m not part of,” explained Kramer. “It’s hard to travel back and forth to Ghana and it’s difficult to bridge the communication gap using email or Skype.”

Kramer and her colleagues also must walk a fine line between American and Ghanaian public health and other cultures. “Since one of the main goals of this project is empowerment, we want to remain very careful about overstepping our bounds and ensuring mutual respect,” explained Kramer.

The Visualize team plans to use various media—television, radio, billboards—to market the availability of midwives for cervical cancer screenings. In addition, the team is collaborating with the Ghana Ministry of Health and Ghana Health Services to vet and publicize its efforts. So far, response from Ghanaian government agencies has been positive. Visualize has found several partners, including the Kumasi Nurses and Midwifery and Training College and the Ministry of Health. Its next step is to identify the location of its first training program.

Ultimately, Kramer said her project is about respectfully furthering social change. “Young people can and should take a more active role in addressing conditions of global poverty,” she said. “But we have to be humble and realistic about our role in societal progress. We have to respect cultural traditions and boundaries and be aware that our presence carries connotations beyond our control.”

The project will be running a fundraising campaign from September 14 until October 14. For more information, go here: crowdfund.berkeley.edu/

Laura D’Andrea Tyson on Social Impact at Cal

By Tamara Straus

Laura D’Andrea Tyson likes to see herself as a communicator and translator of complex economic ideas. But the world tends to see her as one of the most accomplished female economists of her generation. From 1993 to 1995, Tyson was the first female chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisors under President Clinton. From 2002 to 2006, she served as the first female dean of the London Business School. Otherwise, she has worn multiple top hats at Cal: as dean of the Haas School of Business, S. K. and Angela Chan Chair in Global Management, chair of the Blum Center for Developing Economies, and professor of Business Administration and Economics—while also serving as a board member for more than two dozen governmental agencies, private foundations, and multinational corporations.

Laura D’Andrea Tyson likes to see herself as a communicator and translator of complex economic ideas. But the world tends to see her as one of the most accomplished female economists of her generation. From 1993 to 1995, Tyson was the first female chair of the White House Council of Economic Advisors under President Clinton. From 2002 to 2006, she served as the first female dean of the London Business School. Otherwise, she has worn multiple top hats at Cal: as dean of the Haas School of Business, S. K. and Angela Chan Chair in Global Management, chair of the Blum Center for Developing Economies, and professor of Business Administration and Economics—while also serving as a board member for more than two dozen governmental agencies, private foundations, and multinational corporations.

Tyson has sharp, informed opinions on many issues: world trade, international markets, minimum wage, supply chains, underemployment, income inequality, and educational opportunity. One of the subjects that allows her to combine all these threads is “social innovation,” a catchall term for finding societal solutions through multiple and often market-based methods. Tyson believes social innovation and social impact are having their heyday at Cal. Never before have there been so many courses, research projects, and student and faculty efforts devoted to projects aiming to spur social and economic improvement. To point to this phenomenon, the university is launching a campaign this fall called “Innovation for Greater Good: What Can Berkeley Change in One Generation.” The Blum Center sat down with Professor Tyson to talk about the history of social innovation at Cal and where it is moving.

Why did you start the Global Social Venture Competition back in 1999? What in the campus or general environment prompted you to create a social innovation contest for MBA students?

Berkeley was really ahead of its time in supporting socially minded entrepreneurs. This makes sense because the university has always been a progressive place that attracts forward-thinking, diverse students—students with backgrounds that enable them to see societal challenges that aren’t being effectively addressed by either the government or business sector. The impetus for the competition really came from the students. Remember, these were the days of the anti-globalization movement and the beginning of triple bottom line investing. Our MBA students were really fascinated by the new spate of companies that aimed to sustainably support people, environment, and profit. The very name of the competition made the students’ intentions clear. “Global” was used because students wanted their solutions to have international application. “Venture” connoted something new, something risky and creative. And “social” indicated challenges unaddressed by government or the private marketplace. Goldman Sachs had just gone public and had created a foundation, which liked our competition idea and agreed to fund it. Sixteen years later, the Global Social Venture Competition is global itself. The competition brings together a significant network that receives about 600 entries annually from close to 40 countries. Finalists have included social enterprise stars like Husk Power, Revolution Foods, and d.light design.

What has changed in the environment and among the students since the contest began?

I think there’s more emphasis on technological innovations and solutions. The rapid growth of digital technologies and mobile phones has made it easier for organizations to get to the populations they want to serve. The students who are coming to Cal today really get this and want to use technology for social impact. There are also more students coming into the social impact area with engineering backgrounds. They want to be innovators and they want to team up with students from other disciplines—from business, computer science, data analytics, behavioral economics, and social psychology—to form their own organizations while still at Cal. What we’re seeing is the startup culture blossoming and bearing fruit at the university. It’s very exciting to think about where all of this will lead. The other thing that has changed in the last 15 years is the increase in funding options for the research and development of social impact projects. Social innovation students today need more knowledge about financing and the availability of contests, foundations, and venture capital sources. We are working to give them that knowledge.

Why do business schools like Haas make a distinction between entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurship? Isn’t all entrepreneurship social in that it creates jobs?

Social entrepreneurs are motivated by the desire to create new approaches to addressing unmet needs and to solving social problems. They may form a nonprofit enterprise or a for-profit enterprise to realize their goals, but even when they choose a for-profit approach, they place priority on purpose rather than on profits—or on “profits with purpose.” Traditional entrepreneurs focus on for-profit business opportunities and place priority on the profits generated by them. For-profit businesses always have the purpose of serving customers—and profitable companies also serve to employ people and generate returns for their owners. Indeed, many profitable companies make contributions to their communities and some even establish their own foundations to do so. But if a “social purpose” isn’t the original intent of a for-profit business, it is usually not considered a social enterprise. For-profit enterprises produce goods and services to satisfy market demand and demand is based on income. So markets and for-profit enterprises cannot meet the needs of those who do not have adequate incomes to buy the goods and services they need. Governments can address their needs either by raising their incomes or by providing the goods and services they need at subsidized low prices. Social entrepreneurs, nonprofits, and social enterprises also play this role and are essential when governments lack the resources or the political capital to do so.

You’ve called social entrepreneurs a “new kind of business hero.” Is it because entrepreneurs need to distinguish themselves from unethical or anti-egalitarian business practices?

No. What distinguishes social entrepreneurs is their desire to find new ways to address needs that are not met by markets and to address social challenges that sometimes result from negative market externalities, such as pollution, or from positive market externalities, such as the society-wide benefits of an educated population. Broadly speaking, the “social sector” is defined by these broad purposes and includes nonprofits, governments, social enterprises, and for-profit businesses, often working in collaboration with one another. In the U.S., the social sector includes a new form of for-profit business, called a “B” or benefits corporation that embraces both explicit profitability and sustainability goals.

You’ve been involved in the Blum Center for Developing Economies since its creation in 2006. What attracted you to the mission of the Blum Center and how has it supported social innovation at UC Berkeley?

My initial fields of study were economic development, international trade, and what used to be called comparative economics and is now called political economy. So I have always been interested in how societies try to develop and provide rising living standards for their citizens—what is today called inclusive growth. These interests very much align with those of the Blum Center. The center has made three key contributions to social innovation at Cal: through its Global Poverty & Practice undergraduate minor, through its Big Ideas @ Berkeley competition, and most recently through the PhD minor Development Engineering. The GPP minor has been an important contribution not just for Berkeley but also as a model for other colleges and universities seeking to teach students about the causes of global poverty and ways to alleviate it. Big Ideas has provided motivation and support to thousands of students seeking new new ways to address social challenges and have social impact both on and off campus and around the world. And Development Engineering is designed to help graduate-level engineers and social science students who want to use their time at the university to focus on technology for development. Through these educational programs and through the numerous research projects it supports in conjunction with its work with USAID, the Blum Center is fostering the creation of new technological solutions for inclusive economic development.

What can Cal do for its social innovation programs over the next 10 years?

UC Berkeley is a public institution with a long history of community engagement and progressive causes. Support for education and research that fosters positive social impact is deeply embedded in Berkeley’s culture, and there is strong student and faculty interest. There are numerous courses, research projects and activities that focus on social impact across the campus—at the Haas School of Business, the School of Public Health, the Engineering School, the College of Natural Resources, the Blum Center, and several other schools and departments. The Blum Center serves as an interdisciplinary hub bringing together students and faculty from many disciplines with a shared interest in poverty alleviation and economic development. Over the next decade the campus should build on the success of the Blum Center, providing support for interdisciplinary programs that allow students and faculty to design, test, and scale technological and organizational innovations that address unmet needs and social challenges. These programs should take advantage of new modes of education and collaboration made possible by online learning and online social networks.

Alice Agogino: Trailblazer in Mechanical Engineering

By Tamara Straus

When historians get around to investigating the trials and triumphs of women scientists in the late 20th century, they would do well to spend some time looking at the career of Alice Merner Agogino.

When historians get around to investigating the trials and triumphs of women scientists in the late 20th century, they would do well to spend some time looking at the career of Alice Merner Agogino.

Agogino, the Roscoe and Elizabeth Hughes Professor of Mechanical Engineering at UC Berkeley, was the only female mechanical engineering student in her 1975 graduating class at the University of New Mexico and the first woman to receive tenure in her field at UC Berkeley. She said before she joined the faculty in the mid 1980s, the mechanical engineering department decided to vote on whether a woman professor could teach mostly male students. The department seems to have voted yes, because for 30 years running Agogino has taught a majority of men.

In a meandering interview covering women in science, the new discipline of Development Engineering, and the interests of Millennial students, Agogino, an affiliated faculty member of the Blum Center, admitted that for years she insisted engineering was gender neutral. “Until it just hit me in the head: everything is gendered,” she explained with a peal of laughter. “It wasn’t until I started reading Why So Slow, for example, and did the “Beyond Bias and Barriers” study for the National Academy of Engineering and read all the surrounding literature, which was so scary and shocking, that I realized everything is gendered: what problems you select to work on; who makes the technology decisions; who benefits. There’s hardly anything we do that doesn’t have a gendered and social justice component. Now that my eyes have been opened, I can’t go back. I see it everywhere.”

Agogino explains that not thinking about gender was simply a means for survival—“so that whenever something went wrong, I didn’t internalize what happened and say, ‘It’s because I’m a woman.’” As for her academic interests, she credits her parents. Her father was a professor of anthropology and her mother occupied the rarest of 1950s female professions: physics professor. Agogino grew up in New Mexico and spent a lot of time accompanying her dad on archeological digs, ethnographic studies, and academic meetings. Meanwhile, her mother went about her career duties largely childless, lest she appear unprofessional. “My mother got paid half the wages of the people she supervised when she worked in industry,” recounted Agogino. “She thought that was okay or at least she didn’t complain. That’s how she survived.”

Looking back at her mother’s career trajectory and her own, Agogino joked that a caveat should be made to the logic-based field of decision analysis. Decision analysis stipulates that information always has some value. It can have zero value, but never negative value. In the case of being a lone female in a competitive, male-dominated field, Agogino said, again with laughter, “I’m wondering if that’s always true.” Indeed, she and many women of her generation have gotten ahead by blindly ignoring the evidence of sexism around them.

But that is changing. With ever-quickening pace, educational institutions, tech companies, and government and private funders are starting to worry about the low numbers of women in the fields of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math—the mighty STEM of 21st-century progress and high paying jobs. The National Science Foundation has been launching various programs to improve the standing of women in sciences after confirming, in a recent study, that men hold 70 percent of jobs in science and engineering professions. An equally pressing concern is the paucity of minorities in STEM fields. African Americans hold only 5 percent of jobs, according to the 2013 NSF report, and Latinos hold a mere 6 percent.

Agogino said the physical manifestations of these percentages have been sitting in her classroom for years. “When I started at Berkeley,” she said, “I would occasionally have classes in which there not a single woman. In required classes, there were about 5 percent women. It went up to 10 percent, and now I think it’s at about 20 percent. I kept thinking: This is crazy!” To see if she could reach greater gender equity, Agogino conducted a pedagogical experiment. In 2003, she developed a freshman and sophomore course called Designing Technology for Girls and Women. The reading and coursework were solid product design for engineering; the only twist was the intended users—females. The central question was: Would you design differently for women and girls? Agogino’s course attracted 90 percent women. She knew she was onto something.

A few years later, she taught the same course, but widened the scope to emphasize diversity. Lo and behold, almost all of the under-represented minorities in the College of Engineering enrolled, as well as many women. That was also when Agogino started to involve herself and her students more in off-campus social impact classes, like the Seguro Pesticide Protection Project, a system of products to protect Central Californian farmworkers from pesticide exposure, and the Pinoleville Pomo Nation renewable energy and sustainability collaboration, in which Cal students and faculty worked with a local Native American tribe to create green housing.

In these efforts, she found numerous interests coming together: projects for social justice and impact; increasing the ranks of female and minorities in her field; and helping to mainstream “design thinking” and “human-centered design”—two product design approaches that focus on the needs of users or consumers to create more innovative, effective, and sustainable products and solutions.

For these efforts, Agogino has been widely recognized. She just won the 2015 ASME Ruth and Joel Spira Outstanding Design Educator Award “for tireless efforts in furthering engineering design education.” She has been named Professor of the Year, and received Chancellor Awards for Public Service, a Chancellor’s Award for Advancing Institutional Excellence, and a Faculty Award for Excellence in Graduate Student Mentoring. She was elected a Fellow of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, has won many best paper awards, been honored with a National Science Foundation Distinguished Teaching Award and a AAAS Lifetime Mentor Award, the latter for increasing the number of women and African- and Hispanic-American doctorates in mechanical engineering. Her work in decision-analytic approaches to engineering design led to a whole new field of research, and her research in mass customization became a patent-buster for licenses in database-driven Internet commerce. So thank her when you don’t pay a licensing fee to purchase something on the Web.

When asked what she would have done differently, Agogino quipped: “I would have avoided administrative positions and assignments that were not valued. I would have asked for maternity benefits.”

These days, Agogino is focusing some of her energies on creating a new field, Development Engineering, whose mission is to reframe development and the alleviation of poverty by educating engineering and social science students to create, test, apply, and scale technologies for societal benefit. Agogino said Development Engineering students are learning “21st century skills”—interdisciplinary, team-based methods that are oriented to seeing problems from multiple viewpoints (quantitative, qualitative, ethnographic) and applying them through entrepreneurial pathways. The first year of courses, which Agogino co-taught with Business Professor David Levine with support from the Blum Center, attracted record numbers of women and minority graduate students. The reasons, said Agogino, are not mysterious. “They want to use technology for good.”

Agogino added that students and faculty are embracing Development Engineering for a host of other reasons. For faculty, there is now an academic infrastructure for work that had been relegated to weekend projects—work in developing regions that was neither recognized or supported by their specific fields. “We now have a dozen departments represented,” she said. “And there is real joy in working with faculty who care about these issues and want to move forward by learning from each other.”

Yet the greatest push for the Development Engineering PhD minor, said Agogino, has come from graduate students who want the university to create a clearer academic trajectory for interdisciplinary research for social impact. “I have had PhD students who have felt they were demeaned because their research did not fit into traditional engineering pathways,” said Agogino. “This will be changing, due to the scholarship of Development Engineering.”

Yet Agogino does not expect Development Engineering students to have traditional career pathways. They will work for startups, government agencies, nonprofits, universities, and multinational companies, she said, and probably jump around a lot. This risk-taking outlook coheres with what Agogino sees among her other UC Berkeley students. “The climate and push for innovation is coming from the Millennials,” she said. “They’re willing to take risks. They’re willing to forgo instant gratification to do other things that they find exciting, and some of that happens to be in the social arena.”

Agogino explained that she gets behind these students because they want to fight the status quo. They also likely remind the trailblazing professor of herself.

Moving Beyond Benevolence and Cynicism: The Global Poverty & Practice Minor (A Graduation Speech)

By Danielle Puretz

Good afternoon friends, family, faculty, and graduates. For many of us the Global Poverty courses we have taken together have been our most intimate. In this room alone, I am surrounded by mentors and peers among whom I have not only found meaningful inspiration but also deep camaraderie. So it is truly an honor and a privilege to be here addressing you today.

Good afternoon friends, family, faculty, and graduates. For many of us the Global Poverty courses we have taken together have been our most intimate. In this room alone, I am surrounded by mentors and peers among whom I have not only found meaningful inspiration but also deep camaraderie. So it is truly an honor and a privilege to be here addressing you today.

The Global Poverty & Practice minor is set up as a journey, and through our coursework we begin what becomes a recursive practice of questioning and critiquing strategies of poverty alleviation, the ethics of “global citizenship,” and where we lie within those discourses ourselves.

What makes our minor unique is our Practice Experience: the main requirement of which is time, a simultaneously minuscule and yet inconceivably large 240 hours.

For my Practice Experience, I focused on arts education and New Orleans.

Looking back, my Practice Experience was one of the most formative experiences of my time at Cal. Although upon returning to Berkeley, it didn’t feel formative, it felt incredibly unsettling, and I felt lost. I was unsure if I had made the right decision by going to New Orleans in the first place and I was feeling equally uneasy about then having to leave and come back to school.

Within the minor, we are taught to challenge the problems and ethics of voluntourism—destination-volunteering that benefits tourist volunteers more than “beneficiary” hosts. In critiquing this increasingly common phenomenon of service trips, we have to ask ourselves if this is also what we are setting ourselves up for with our practice experiences—doing “more harm than good.”

A number of times within my own Global Poverty journey, I’ve been required to read Ivan Illich’s “To Hell With Good Intentions.” As a speech he gave to Peace Corps volunteers almost 60 years ago, Illich’s words are as acerbic as ever: “The damage which volunteers do willy-nilly is too high a price for the blated insight that they shouldn’t have been volunteers in the first place…I am here to challenge you [he explained] to recognize your inability, your powerlessness and your incapacity to do the ‘good’ which you intended to do.”

As Global Poverty & Practice Minors, I believe that we have the best intentions.

However, we have surely put our fingers in our ears if, at any moment, we felt as if our benign intentions are enough. As we’ve all learned, the world does not begin the day we set out to do good. We are predated by centuries of systemic exploitation, which created the very poverty we so benevolently seek to eradicate. The courses we take in Global Poverty are meant to help us understand this history and our own positionality, as we set out to do social justice related work.

Along this journey, I have had quite a few moments of self-doubt, many of which somehow coincided with reading articles such as Illich’s. In these moments, I have found some distraction by mulling over a paradox Professor Ananya Roy shared with us Global Poverty 115: “To find ourselves in the space between the hubris of benevolence and the paralysis of cynicism.”

I remember initially hearing Professor Roy say these words in lecture, and it felt like a prophecy that would define the rest of my time within the minor. I arrived at Global Poverty, because I had such arrogant dreams of wanting to fight inequality and end poverty. I wanted personal fulfillment and the affirmation that I was indeed doing good work while contributing in some way to global change.

When Professor Roy’s words set in, I felt like a mirror had been held up to my ambition. I realized that this was my hubris—to think that with my good intentions, nothing I did could be conceived as anything other than altruism. In my will to change, I began to fear a trajectory where I would learn more and more about a world filled with greed, cruelty, and despair, only to be left in a psychosomatic paralysis. I was no longer just afraid of doing more harm than good; I was also afraid of becoming someone who would do nothing. As my fellow GPP student Shrey Goel mentioned, ignorance is ethically indefensible, but so too is choosing inaction. Thinking that neutrality might not be a political decision in itself is an expression of complicity in systems of exclusion.

Feeling pulled in different directions, motivated toward public service, but afraid of doing more harm than good, and terrified of doing nothing, I decided to let my curiosity get the better of me. Thus I proceeded to plan my practice experience in New Orleans.

Part of this planning is guided by the minor curriculum—thorough education and significant time commitment, we aim to set ourselves apart from volunteers who are more visibly in it for themselves. The minor facilitates “praxis”—the combination of theory and practice. We believe that sustained commitment and thorough education allow for us to build better relationships with the people we are working with. That these efforts may substantiate our presence where we are not solely putting more work on their plates. In New Orleans, I felt my own expectations to test myself, my knowledge, and my character—and have the depth and richness of the relationships I was building act as the metric for my achievement.

But when I returned to Berkeley, I felt ripped from all of the people I had been working with.

Fortunately, as Shrey so beautifully laid out, we are taught a self-reflective praxis, and experience this firsthand through our shared catharsis in the capstone course. I arrived on the first day of Global Poverty 196 not looking to be validated, but searching for some resolution and justification for the work that we did. I believe that all of us will remember Professor Khalid Kadir’s extravagant metaphor about climbing hills and mountains, building to his point that “there is no Mount Everest.” There is no end to the work we do; there is no closure or final affirmation that should ever go un-critiqued.

In looking at the Global Poverty journey as an educational experience, I want to suggest that there is value to this feeling of being unsettled. As Professor Clare Talwalker quoted Paulo Freire in our Methods course, “Those who authentically commit themselves to the people must re-examine themselves constantly.” I think that this practice of constant critiquing, questioning, and challenging is exhausting, but the unsettled feeling that comes with it is a discomfort that comes from learning, and it is necessary if we want to “do good” or at the very least learn from our mistakes.

Yet despite this realization, my anxiety about my hubris and potential to become paralyzed by cynicism lingered throughout my time in the capstone course. I was hanging onto the hope that I could grow out of my hubris without tumulting into such an opposite extreme. And on the very last day of this class, as I was still searching for my place along the spectrum of hubristic benevolence and paralyzing cynicism—I became critical of the dichotomy this analysis suggests.

I realized that another state to be wary of is the hubris of cynicism.

As we learn to constantly critique ourselves, it becomes easy to lapse into cynicism. And as we develop an association of cynicism to intellect, we learn that in playing pessimist, we may seem smarter or more well seasoned, an expert even. Cynicism acts as a shortcut, providing the guise of experience—that we’ve seen a lot and it doesn’t look good. I have learned that if I am cynical as I describe myself, I seem well versed in criticism, somehow more keenly aware of myself and the world around me. But how conceited is that? To think that we could ever know so much that we may be above the people that we work with and learn from, that their efforts aren’t enough, that our skepticism is superior to a tenacious perseverance of hope—makes me feel that cynicism is fundamentally twofold with a dangerous hubris.

To me, conflating hope with naiveté and cynicism with intellect demonstrates an arrogance that may need more than reflection to eradicate. As we hear “to hell with good intentions,” we need to be able to feel the discomfort that we may be doing the wrong thing, without using cynicism as a coping mechanism.

As I share with you one of my newfound fears of cynicism, I want to also reassure you of my faith in us to overcome it. Our minor has encouraged us to explore ourselves and given us theory to understand the space we occupy. And while our practice experiences were the climax of our journey, the core of our minor is community. It is no coincidence that we go through the different stages of this minor together, we are reflecting together, we are asking deeply personal and difficult questions together. Social justice work is difficult, but we share this responsibility, and take on these challenges in community.

Now we’re graduating, which is scary in and of itself. We must take with us our ability to understand complexity. My mom is an elementary school teacher, and when she takes her class outside to play softball she doesn’t keep score—she tells them that they are just out there to exercise. She has worked with children longer than anyone I know. Her expertise comes from her lived experience, and it is so visible when I go to her school and see how loved she is by her students, their families, and her colleagues. My mother has been my main teacher my whole life. The classroom she cultivates is a space free from failure, which I think is especially important for her second graders, so that they can learn to keep trying without fear of some ultimate failure. And in my understanding of complexity, education is a point of stability, where our failures are somewhat cushioned. So as we depart from that, we need to work on cultivating within ourselves an acceptance of failure as well as metrics of success where we do not find validation within the failures of others. We need to be able to dish out criticism as well as take it; we need to be understanding of unease, and comfortable with failure. We need to recognize that these are challenges that we need to work with, learn from, and find motivation to try again.

We now occupy a space of “educatedness”—able to understand that problems are more complex than meets the eye, that narratives are shrouded with hegemony, and that we must challenge the notion of expertise, while also doing justice to our educations. Recognizing that our degrees bring power and we are on some level experts ourselves. We are brave and we are curious; we are arrogant and we are fearful. Still, I am confident that our education and lived experiences have taught us the strength and humility to push back against injustice as well as the ability to receive the personal criticisms we undoubtedly will encounter. To do nothing is to accept the world as it is. To challenge and critique our world is ultimately an expression of hope: that while we will never reach Utopia, we can still work toward a better tomorrow.

At the very least, I hope we have learned that we are not alone. It has been an honor and a privilege learning with and from all of you. Thank you, and congratulations.

Danielle Puretz is a recent graduate with degrees in Theater and Performance Studies and Peace and Conflict Studies as well as a minor in Global Poverty & Practice. She has been selected for the John Gardner Public Service Fellowship, and will be spending the next year continuing her exploration of theater and social justice-related work.

Put Innovators to Work on Making Clean Air Affordable in China: An Op-Ed from Design for Sustainable Communities Student Ming Zhang

http://www.scmp.com/comment/insight-opinion/article/1826769/put-innovators-work-making-clean-air-affordable-china

For Cal Students Looking to “Do Good”: The Global Poverty and Practice Minor (A Graduation Speech)

By Shrey Goel

The pre-Global Poverty & Practice Minor student is a particular, but not unique, sub-species of the Berkeley undergraduate. Often, these students come to Berkeley impassioned but without direction. They want to challenge the status quo, advocate for those in need, and represent a cause that is being ignored. Deep down, they just want to do something meaningful. I know I certainly did—I had a desire to “do good,” and maybe a bit of me even believed that desire set me apart from others. You see, my parents taught my siblings and me to always recognize our privilege and value the idea of “giving back” to those in need. In high school, I began to tap into that social consciousness, exploring issues like social welfare, affirmative action, and inequality. So perhaps you can understand that for many in my cohort, myself included, when we first heard about the Global Poverty & Practice Minor, there was no question about it – this was our mission, what we came to Cal to do. GPP was our calling because we cared about poverty and inequality. What we may not have realized then is that we were late to the game; GPP was already one of the largest minors on campus and the debates about how to address poverty had already been raging long before we even arrived at Berkeley.

But perhaps it’s a good thing we didn’t realize it at the time. Our naiveté made us ideal candidates for what GPP can offer. I must confess, I had never cared enough about course material to take notes the way I took them in GPP 115, the inaugural class into the minor. Sitting in Wheeler Auditorium, I found my hand scribbling away, racing to capture the nuance of every point of Professor Ananya Roy’s impeccably delivered lectures. Those lectures were riddled with ethical dilemmas, forcing us to confront ideas like the savior complex, simplistic notions of the poor as victims without agency, and the development industrial complex. And at the end of the day, the message was this: you are guilty. We are all inextricably implicated in systems of power. There’s no silver bullet but ignorance is ethically indefensible. So what will you do?

At it’s best, what GPP does is lure us in, with our fledgling social consciousnesses, and throw us into debates raging in the world of poverty and development. In doing so, the minor presents students with an opportunity to contribute to those debates. Then, through the help of our GPP 105 Methods Course taught by Clare Talwalker and Khalid Kadir, we are taught to engage in a form of scholarship that is simultaneously nuanced, critical, and self-aware, as we learn to contextualize our looming Practice Experiences in the “real world” of development work.

Our Practice Experiences cannot be summarized through any one anecdote. Some of us worked for local organizations, others abroad. Some of us worked in offices, others in the field, some of us performed administrative tasks, others labored to build things. But more importantly, some of us worked for organizations that pursued “Band-Aid” solutions, and some of us for orgs that sought to tackle the causes of poverty at a deeper, more structural level. It wasn’t always something we had control over, and the work was sometimes frustrating for many of us, but in all cases, there was plenty to take in.

Although our Practice Experiences varied, returning from them and taking the GPP 196 Capstone Reflection Course was, for many of us, a cathartic experience. Our instructors Khalid Kadir and Cecilia Lucas pushed us to take our experiences and actually engage in the iterative process of reflection, never allowing us to become complacent in our critical assessment of our organizations or our roles in them. The reflection course provided us with a setting to connect to our peers in the minor—the few other people who could understand what it meant to wrestle with the ethical dilemmas presented by our practicums—and the course facilitators helped us to find support in one another. We came to see that the empathy and perspectives of our classmates were as indispensible to the learning that took place as the mentorship we received from our instructors and the support we received from our program coordinators, Sean Burns and Chetan Chowdhry, who have worked tirelessly behind the scenes to hone and improve the minor.

GPP seeks to mold us into citizens who will advocate for the rights of the marginalized to be heard in the dominant narratives of the global political economy. The irony of pursuing a minor like this at an institution like Cal, however, is that even public education is expensive these days; thus the rising cost of public higher education is excluding many voices from discussions of the very systems which affect them most. Yet another irony of pursuing a minor like GPP is this: if it weren’t for the depth and richness of the GPP curricula, with its focus on teaching us to critique and challenge everything, including our very education, I might not have felt my education was worthwhile. For me, the heart of what GPP offers is all about self-reflexivity. Self-reflexive scholarship, to me, is about never letting yourself off the hook. It’s about challenging yourself, your ethos, and your motivations, as well as the motivations of the people and organizations around you to demand better.

Today we are here to share—to share with you all, our friends, family, and faculty who have supported us, this celebration of all that we have accomplished. But I believe we are also here to share with you our challenge: our mandate as global citizens and graduates of the Global Poverty & Practice Minor. It’s a challenge that I believe is fundamentally about remaining self-reflexive. Holding on to a social consciousness and having social-welfare-aligned political views are simply not enough. Rather self-reflexivity necessitates that we never stagnate in our pursuit of praxis—in the endless oscillation between action and reflection, which inform one another and lead to true learning. Self-reflexivity asks us to never become complacent in self-congratulation and always be willing to point the magnifying glass inwards; as anthropologist Laura Nader encouraged us to do, to be willing to “study up” and critique the power structures of the institutions within which we operate; and also, most importantly, to seek out and always remain accountable to those whom we purport to help, never allowing our voices to speak over those who are being ignored and helping to carve out spaces and build platforms for them to be heard.

Graduating as a GPP Minor comes with a responsibility, and that responsibility is to recognize that the job is never complete, but is also constantly evolving. That job cannot be done alone. So as much as today is about celebration, it is also a call to action. What we students have learned and experienced through the minor is a window into how we all can push ourselves to engage in the discussions and processes of change taking place in communities around the world. So on that note, I’d like to end by recalling the prompt I left GPP 115 with: we are all inextricably implicated in systems of power. There’s no silver bullet but ignorance is ethically indefensible. So what will you do? But more importantly, what will we do together?

Shrey Goel graduated with a minor in Global Poverty & Practice and a BS in Environmental Science, for which he wrote an honors thesis based on his GPP Practice Experience. After graduation, he plans to work in the Bay Area and apply to medical school.

Will student loan debt be worth it? (San Francisco Chronicle Op-Ed by GPP student Amber Gonzales-Vargas)

In 2014, outstanding student loan debt for Millennials surpassed $1 trillion, making it the second largest category of household debt after mortgages.

By Amber Gonzalez

In 2014, outstanding student loan debt for Millennials surpassed $1 trillion, making it the second largest category of household debt after mortgages. These numbers are all too familiar to me and my friends at UC Berkeley. Initially, most of us considered student loans a great trade-off for getting our undergraduate degree, and we have held to that opinion as the loans needed to graduate increased. Yet as we face graduation, these loans are not feeling fair. They feel like a noose around our collective necks, the price of which may be dreams deferred.

As a low-income, first-generation student from Stockton, I have been able to stay enrolled at UC Berkeley through the rising tuition— from $9,342 in 2010-11 to $13,317 in 2014-15 for California residents— thanks to a Pell Grant and Cal Grant A. To cover other living and student costs such as rent, food and books I have worked as a peer adviser and office administrator.

Believe me, I am not complaining. My parents, who are from Peru, have often reminded me that I am lucky to have been born in the United States— and I agree. We assumed my future was set, as long as I excelled in high school and succeeded in college. This path would land me a job reserved for hard-working students from one of the nation’s best universities.

But will it? What is apparent to many of us attending four-year institutions is that a bachelor’s degree does not reserve you a job, even if you are graduating from a top institution. The proverbial entry-level position for recent graduates now typically requires two or more years of relevant work experience. In certain fields, these opportunities are offered as an unpaid internship, a luxury that few can afford to accept, even if it increases the chances of getting a job.

For me and many of my friends, the need for job security is especially high because we face immediate loan repayment. I owe $12,900. Yet I am “lucky.” I took out subsidized loans that do not accrue interest until six months after graduation. Others? My brother, who is at a private university, has taken out unsubsidized and other loans that begin to accrue interest upon signing, and he is only a freshman.

We are all fiercely hunting for a job. We know that not having work lined up this summer will make paying back our loans difficult. One of my best friends, who has accrued about $15,000 in debt, is attending community college as a way to acquire additional skills and to defer her loans for a few more months. She is doing this while working full-time.

Because our immediate futures are limited by loan paybacks, many Millennials may avoid creativity or risk. We may take any job that provides an income, however far from our interests. Down the line, this may also translate into deferment of such life milestones as buying a car, buying a house or having children.

In a March 28, 2014, article, Los Angeles Times columnist Chris Erskine said Millennials will be the greatest generation yet because they are idealistic, adaptive and more tolerant of differences. But Erskine makes no mention of student debt, citing instead a Pew Research Center study of Millennials that found we are the nation’s “most stubborn economic optimists,” with more than 8 in 10 reporting we have enough money to lead the lives they want, or expect to in the future. I wish he and the Pew pollsters had canvassed more of the 80 million Americans between the ages of 18 and 34 whose economic lives are dictated by student debt.

In March 2015, President Obama signed a Student Aid Bill of Rights that argues that the federal government should do more to help young people pay off their crushing loans. He offered several improvements such as a Pay-As-You-Earn plan and a centralized loan website. My experience is that no one really wants to take out a loan, and while this plan sounds like a good way to help young Americans navigate the student-loan system, we should be looking to significantly reduce student loan debt, not just making adjustments to help keep track of debt. Students still will face rising student-loan debt and have to start their careers increasingly indebted.

In the upcoming weeks, the class of 2015 will depart for the working world. We will go on to become teachers and doctors and policemen and data analysts. An estimated 12.7 percent of Californians will default on their debt; the rest will dutifully pay back the banks and the government. Our successors may also fare worse. The UC regents have approved a tuition increase of up to 5 percent per year through the 2019-20; however, the governor has proposed a budget deal that would give UC more funding if UC forgoes the increase and freezes tuition through 2016-17.

Will Americans with such early indebtedness be able to become credit-worthy adults? In a decade’s time, will our earliest financial decisions feel worth it? I certainly hope so.

What Are the Ethics of Humanitarian Technology? An Interview with Blum Center Postdoc Imran Ali in Engineering for Change

Making History: Blum Center Director of Student Programs Sean Burns Profiled in the East Bay Express

http://www.eastbayexpress.com/oakland/making-history/Content?oid=4260987

The Double Burden of Malnutrition: An Interview with Janet King

By Tamara Straus

There is a quotation on the website of the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute (CHORI) that sums up Dr. Janet King’s ability to combine international nutrition expertise and common-sense thinking. The quote says: “We don’t need new lab research to show us the benefits of fruits and vegetables. We need research that emphasizes real-world solutions.”

King, who serves as executive director of CHORI, is not your typical research scientist. In addition to publishing 225 scientific papers, review articles, and book chapters, she has effectively turned nutrition research into public policy. In the early 2000s, she chaired the U.S. Department of Agriculture/U.S. Health and Human Services Dietary Guidelines Advisory Committee, which resulted in the Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2005. She is a member of the National Academy of Sciences, Institute of Medicine; and in 2007, she was inducted into the USDA Research Hall of Fame. She also has directed the USDA Western Human Nutrition Research Center at the University of California, Davis (1995-2002) and chaired the Department of Nutritional Sciences at University of California, Berkeley (1988-1994).

The Blum Center sat down with Dr. King, a Blum Center advisor, to learn more about the connections between child nutrition and socioeconomic development.

When did child diabetes rates start to spike in the United States?

We began to see a rapid increase in the incidence of obesity in children in the 1980s. However, the association between obesity and Type 2 diabetes didn’t make it into the scientific literature until 20 years later. I can only speculate why this is. It might be because the incidence of obesity in children hadn’t reached the threshold where the association with diabetes was apparent to medical staff. Nonetheless, these days about 45 percent of all cases of diabetes in children are associated with obesity and are type 2 diabetes. Whereas in the 1980s, the only time we saw diabetes in children was when it was type 1. As that time, we would call type 2 diabetes “adult onset diabetes,” because it was so rarely seen in children.

What were the chief reasons for the 1980s rise in child obesity and diabetes in the U.S.?