After a semester studying housing, transit and other issues plaguing the Bay Area, a group of UC Berkeley students has some unexpected solutions. Free buses, anyone? How about a podcast on homelessness?

Author: Joseph Kim

April 2019

Big Ideas Grand Prize Pitch Day Showcases Inventions of Top Student Teams

In 2006, the Big Ideas Contestlaunched at UC Berkeley to catalyze and support an interdisciplinary and diverse network of student entrepreneurs to develop game-changing innovations. No longer would entrepreneurship be ensconced within just engineering and business schools and accessible to only a few. The time had come to “open-source” entrepreneurship to include the range of perspectives and interdisciplinary expertise necessary to develop well-rounded solutions to the world’s greatest challenges.

From Bean to Cup: Anti-Trafficking IdeaLab Develops App for Ethically Sourced Coffee

By Chloe Gregori

Whether students are cramming for late night exams, needing a spike of energy during a 9 am lecture, or studying at a local Berkeley cafe—coffee embodies the college experience. In fact, 54 percent of Americans over the age of 18 drink coffee every day. Coffee is worth over $100 billion worldwide, placing it ahead of other global commodities like gold, natural gas, and oil.

However, this massive and lucrative industry is not without social cost. The complex supply chain—from coffee bean to cup—tends to funnel money to corporations in wealthy countries from farmers in poorer countries, where the beans are arduously picked by hand. In 2016, two of the world’s biggest coffee companies, Nestlé and Dunkin’ Donuts, admitted that beans from Brazilian plantations using slave labour may have tainted its coffee products. Overall, coffee is one of the most notorious industries for human rights abuses. Workers are vulnerable to low wages, exploitative work conditions and, at worst, forced labor and human trafficking.

The Berkeley Coffee Project, an initiative under the Anti-Trafficking Coalition, which is a Blum Center-sponsored IdeaLab, is aiming to empower students to become more conscious consumers and educate them about labor practices connected to their everyday purchases. As the Berkeley Coffee Project Planning Chair Sophia Arce states, “To minimize human rights violations within this industry, it is up to us, the consumers, to demand products that hail from a fair, transparent supply chain.”

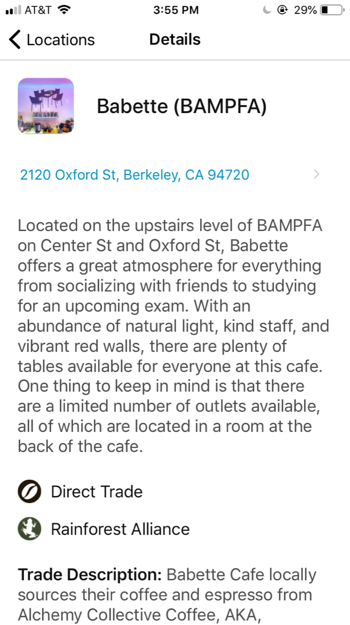

Arce, a senior Global Studies major, led a team of over 30 students from diverse disciplines to develop “Conscious Coffee”—an app that allows students to easily find ethically sourced coffee near the UC Berkeley campus. The app includes a list of 30 partner cafes sorted by distance from user’s location, sourcing certifications (along with explanations of their meaning), and links to each cafe.

To launch the app, the team hosted Coffee Festival in early April, an event for students to learn more about local companies that use ethical sourcing and get their fair share of free coffee products. The festival featured campus vendors, such as CalDining (which sells Fair Trade coffee via its partnership with Peets) and Equator and local businesses like COBA, Sweet Maria’s, FORTO, and Rebbl. Students also learned from Berkeley Coffee Project representatives about the difference between fair trade, direct trade, USDA Organic, and a range of sustainability labels.

“Understanding the labels is a basic step, but there are so many ways for products to be ethically sourced,” Arce explained. “It’s important not to accept labels at face value and do your research.”

The Berkeley Coffee Project plans to recruit more cafes to be listed in the app and create a purchasing rewards feature.

“There is a perception that products with labels like Organic or Fair Trade are too expensive for the general population to afford, let alone college students scrambling to afford Bay Area housing costs and overpriced textbooks,” said Arce. “If the goal of ethically sourced products is to empower economically marginalized populations, shouldn’t they be accessible to consumers who also struggle financially?”

Arce said this irony inspired her to add a rewards system for future app development.

“Not only do I want to provide Cal students with the information they need to make conscientious consumption choices, I want to give them the financial resources to make these choices viable.”

Want to learn more about ethically sourced coffee near campus? Download the Conscious Coffee for Android here or on the Apple App Store.

Big Ideas Winner Po Jui “Ray” Chiu, co-founder of BioInspira Inc., named in the Forbes 30 Under 30 Energy category

In July 2014, a series of natural gas explosions ripped apart Kaohsiung, a Taiwanese city where Po Jui “Ray” Chiu, MEng ’14 (BIOE) had lived with relatives just a year before, while he was completing his compulsory military service.

February 2019

http://pub.lucidpress.com/cf2314aa-5977-4fb4-a6d9-94891b5a2e8e/?src=em

Big Ideas Innovation Ambassadors Nurturing Ideas into Enterprises

By Lisa Bauer

Founded in 2005 at UC Berkeley, Big Ideas has become one of the largest and most diverse student innovation competitions in the country. The contest supports the next generation of social entrepreneurs–providing mentorship, training, and the diverse resources required to support big ideas from their earliest stages. In 2017, to ensure the contest remains accessible to the widest number of students across UC’s ten campuses, the Big Ideas team designed an Innovation Ambassador program.

Tainted Garments

Pursuing a Career in Engineering Co-Design: A Q&A with Ryan Shelby

By Tamara Straus

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his dissertation unusual. Shelby’s PhD research went beyond traditional engineering. It presented design theory and methodologies and was based on his involvement in building sustainable housing and renewable power systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation in Ukiah, California.

When Ryan Shelby left UC Berkeley with a PhD in Mechanical Engineering in 2013, he and his advisor considered his dissertation unusual. Shelby’s PhD research went beyond traditional engineering. It presented design theory and methodologies and was based on his involvement in building sustainable housing and renewable power systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation in Ukiah, California.

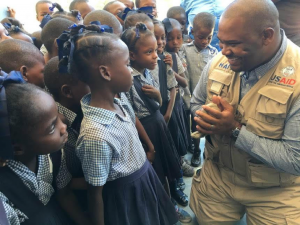

“Looking back, I was a bit of an odd duckling,” said Shelby, now a Diplomatic Attaché and Foreign Service Engineering Officer at the United States Agency for International Development in Haiti. “I wanted to do PhD work that was applied and more meaningful in a development context.”

Shelby failed his first qualifying exam. But the setback forced him to delve beyond engineering and become a technology for development polymath. He steeped himself in business, environmental science and policy, ethnographic studies, development theory, information technology, and the history of Native American tribes. When Ryan was handed his diploma, he continued along this interdisciplinary path. During the summer of 2013, he served as a Science, Technology & Innovation Fellow at the Millennium Challenge Corporation. He then worked in Sub-Saharan Africa and other emerging regions as a senior energy advisor for the U.S. Office of Energy and Infrastructure, landing in 2016 the position as a USAID foreign service engineering officer.

At USAID, Shelby has been developing and managing Haiti’s Build Back Safer II program, for which he recently won an award. Build Back Safer II provides local job training and material sourcing for hurricane-resistant building structures. To date, the program has resulted in 4,000 home roof repairs, the training of over 2,000 people (60 percent women) in roof rehabilitation techniques, and the completion of scores of handwashing and toilet facilities in areas damaged by Hurricane Matthew. Build Back Safer’s II next stage of repairs will focus on microgrid rehabilitation, water point upgrades, and sanitary block restoration in health clinics.

At UC Berkeley, Shelby remains a model for engineering Berkeley PhDs who want to do interdisciplinary research in low-income regions and use their technology skills. The graduate program in Development Engineering comes in part out of his quest to do applied engineering at the dissertation stage. To learn more about his trajectory as well as his views on engineering co-design, the Blum Center spoke with Ryan Shelby from his USAID office in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

How did your upbringing influence your academic and career pursuits?

I grew up in really rural Alabama, in Letohatchee, where there were about 600 to 700 people. My Dad had a farm there. I always liked to tinker—mess around with my Dad’s tractor, take apart my Mom’s vacuum cleaner. Luckily, my parents indulged me and I had a natural affinity for math. They let me to go to Alabama Agricultural & Mechanical University, an historically black college that had a very good engineering program. I majored in mechanical engineering with a focus on propulsion systems. It was 2003/2004 when President Bush talked about going after more alternative, sustainable energy approaches. That was pretty exciting to me, but Alabama A & M didn’t have an energy program. That’s when the dean of my university, Dr. Arthur J. Bond, told me about UC Berkeley and Professor Alice Agogino. He made the connection for some mentoring with her, and she encouraged me to apply. She said I could pursue design, energy, and engineering work.

Would you advise engineering PhD students to do applied work while in university?

In academia, there’s a lot of amazing ideas and technologies. But transferring those ideas into a practical technology that can be built and implemented at scale and have impact within a short time horizon—that’s not something easily done. Still, I would encourage people do this in an academic setting, because it’s a lot easier to do theoretical and applied work and fail and learn from those mistakes, as opposed to when you’re out in the policy world or in industry. The more you ideate, the more you fail, the more information you gather. It allows your next version to reach a more optimal solution.

How does USAID view university-incubated innovations?

The applied work university researchers do makes it a lot easier for us on the government side to say, “It’s been peer-reviewed and tested. Now let’s learn from what the Ivory Tower has done and integrate the work into our projects.” That’s how USAID under the Obama administration and now under the Trump administration is approaching university innovators. We realize universities have great ideas; they may be too high risk for industry to fund. But the U.S. government is willing to make informed decisions to invest in these technologies, so we can grow them and integrate them into our work—and ideally leapfrog pitfalls some countries face in their self-reliance and overall growth.

Are you working with universities in your Build Back Safer II program in Haiti?

Yes, we are partnering with the American University of the Caribbean in Les Cayes, Haiti and the Swiss Development Corporation to develop training programs on rehabilitation techniques and housing upgrades for homes and other vertical structures that were damaged by Hurricane Matthew. We identify masons and carpenters and others in the community who have some technical skills and interest in learning new vocational skills, and train them in hurricane repair and making proper foundations. We’ve combined that with vendors in the area, to source the right materials, so they can go out and implement a lot of these repairs—on roofs, water distribution points, and on two solar microgrids in the southern part of Haiti.

What combination of skills did you deploy to develop this program?

I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.

I designed this program because of my experience with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation. Coming in and putting in a solution that does not fit the cultural context is not the best way to ensure sustainability and self-reliance. Rather, you need to understand community needs, understand situated knowledge. In Haiti, we want to give community members access to the latest technology and building techniques. For me, this requires learning the Haitian way of building, and co-creating a shared knowledge base of how we can go out and do housing repair work that pulls from these knowledge bases. One the traditional building techniques here is called clissage, where you weave pieces of wood of varying tensions to create strong foundations and vertical structures. What we’re doing is showing Haitians how they can bolt onto clissage more modern and hurricane-resistant techniques for roof design and installations.

Is there a fairly straight line from your doctoral work to your current USAID work?

I told Alice [Agogino] it’s like déjà vu. My work in Haiti is almost a mirror image of the dissertation work I did at Berkeley. It’s still housing, design, and rehabilitation work, and it’s also energy systems to provide electricity to support economic growth. This is the exact thing I did with the Native American tribe. I’m using the same research techniques and codesign methodology with these Haitian communities. If I hadn’t done this dissertation work at Berkeley with Native American communities in California, I would find my job at USAID hard to do. I wouldn’t have the theoretical background or the tangible experience to prepare me for this work.

Which thinkers would you recommend to students in development engineering?

I highly recommend [UC Santa Cruz Professor] Donna Haraway’s work on situated knowledge as a core tenet of co-design and co-creation. Situated knowledge pulls from environmental science policy and feminist theory, and provides an intellectual framework for understanding and utilizing people’s knowledge bases. I also recommend [Harvard Professor] Sheila Jasanoff’s work on the co-production of knowledge and [Rutgers University] Frank Fischer’s work on citizens as experts of the environment. Dr. Fisher writes about how communities work with outsiders to understand environmental impacts and how to try to design and implement solutions.

How has the field of development changing, particularly for the U.S. government?

It really hasn’t changed that much between Administrations. Both the Obama and Trump Administrations have pushed to work with nontraditional actors, including universities. One big difference with development under the Trump Administration is we’ve increased the focus of self-reliance and co-creation. Our goal is to partner with a host country governments and co-design solutions with them, so that the host country itself can do the implementation work and not have to rely fully on the U.S. government. Under the Trump Administration, USAID is committed to streamlining our procurement approaches and increasing the usage of co-creation design approaches within new awards by 10 percentage points in Fiscal Year 2019. We want to continue to partner with universities, partner with private sector, partner with religious groups, partner with other nontraditional actors—so we can get the best technologies, solutions, and innovations to fit the needs of a host country government and get it out in the field as quickly as possible. The aim is to improve their resiliency and self-reliance and reduce their overall dependency on U.S. foreign aid as well as eventually open up new markets for American goods and services.

What would you recommend to Development Engineering students who want to work for USAID and other governmental organizations?

The transition from a more research background into development or the policy arena can be as perilous as crossing the sea with the sirens Scylla and Charybdis on either side. To navigate this path, I would recommend engaging in more applied research while at Berkeley with professors like Alice [Agogino], Alastair [Iles], Ashok [Gadgil], and Dan [Kammen] to get a better understanding of this space. Next, I highly recommend that students consider pursuing science and technology policy fellowship programs, such as the Christine Mirzayan Science & Technology Policy Graduate Fellowship Program at the National Academies, the California Council on Science and Technology, or the Institute for Defense Analyses Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) Fellowship. These programs are designed to help Bachelor, Master, and PhD candidates and recipients to understand how science is utilized in development and policy making. My experience as a Fall 2012 Mirzayan Fellow was instrumental in helping me land my job at the Millennium Challenge Corporation and USAID, as the National Academies taught me how to translate science and engineering speak into the language and format of a policy brief. Moreover, I was able to use my time at the National Academies to conduct informational interviews with development professionals within government as well as in for-profit and nonprofit organizations, to better learn which technology gaps and other seemly intractable problems that were encountering. These interviews and the knowledge that I gained were instrumental in helping me find and land a position at USAID.

Maria Artunduaga’s Mission to Manage Chronic Lung Disease

By Tamara Straus

On February 26, 2018, Maria Artunduaga had a eureka moment that medical entrepreneurs dream of. In the office of UCSF Professor Mehrdad Arjomandi, she was soliciting advice about a wearable prototype she had developed to monitor oxygen in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Dr. Arjomandi—a clinical professor and foremost expert on COPD—was telling her about an air trapping investigation he had been doing for over a decade. He was bemoaning the enormous time and expense involved in testing patients with COPD, the third leading cause of U.S. deaths.

Graduate-Undergraduate Student Mentorships Grow

When Chancellor Carol Christ released UC Berkeley’s strategic plan for 2019-2029, two overarching goals were relevant to the Global Poverty & Practice minor and the Blum Center’s graduate program, Development Engineering.

The first goal was to “empower engaged thinkers and global citizens to change our world. Specifically, Christ wrote: “Acts of discovery—self-initiated projects that create new knowledge—will be a focal point of undergraduate study. Engagement with the world beyond campus, and reflection on the meaning of an education, will also be key to the Berkeley experience. Master’s students will see increased investment in their knowledge and skill-building, and doctoral students will receive added training, mentorship, and financial support.”

The second goal was “focusing on the good: innovative solutions for society’s great challenges.” Christ explained, “Faculty, staff, students, alumni, and our larger community will come together to address the great challenges of our time that Berkeley is particularly well suited to address, including technological change and artificial intelligence; environmental sustainability; the future of democracy; inequality; human health; and the future of public higher education.”

These two goals are already integrated into Global Poverty & Practice (GPP). They also are being exercised in several new mentoring arrangements between GPP and Development Engineering students focused on socioeconomic solutions with community groups and NGOs.

Take the Pinoleville Pomo Nation collaboration. Since 2017, several GPP and Development Engineering students have been working with a Native American tribe of 300 people based in Ukiah, California and an interdisciplinary UC Berkeley group called CARES—Community Assessment of Renewable Energy and Sustainability—to co-design STEM education activities for native students.

For George Moore, a UC Berkeley Mechanical and Development Engineering graduate student, the project has been a means to further educational equity and gain teaching skills. He recounted that both graduate students and undergraduate students, such as GPP student Arielle Dollinger, were able to co-design the 2018 STEM education workshop with community members.

“Among the decisions we collectively made were to teach engineering design through Pomo Pinoleville basket-making techniques and to engage students in 3D printing designs from local art and nature,” said Moore.

Dollinger said the CARES-Pinoville Pomo Nation project was appealing for her GPP Practice Experience because she wanted to work locally and in an interdisciplinary vein.

“It was really up my alley because I’ve taken Native American Study classes and I am committed to environmental justice and social equity,” said Dollinger, who added that the Development Engineering team was “very open to undergraduates contributing input and insights and opinions. We conducted weekly meetings throughout the spring semester, and I felt I was part of the development of the project. Also, just having the opportunity to work with a California indigenous community was a huge privilege and honor.”

Another recent mentoring collaboration between Development Engineering and GPP students involves Visualize, founded by Mechanical Engineering PhD student Julia Kramer. Kramer started the project—a healthcare design and training program to teach midwives in Ghana to screen women for cervical cancer—as an undergraduate at University of Michigan and continued it during her summers at Cal, winning a Big Ideas award in 2015. In the fall of 2016, she decided to connect to a Cal group called Invention Corps, to find project assistants. There, she met Iris Huo, an undergraduate economics and GPP student, who has since worked with Kramer to iterate on Visualize and, during the summer of 2018, accompanied her to Ghana.

“I understood right away the tangible impact of Visualize to affordably and effectively reduce mortality rates in women,” said Huo. “The work has been the most life-changing experience I’ve had, especially what I learned in Ghana. And Julia, to this day, remains the paragon of mentorship that we have at Invention Corps.”

Kramer—who is mentored by Blum Center Education Director Alice Agogino, a nationally recognized expert on mentoring students in interdisciplinary engineering—has found the collaboration equally rewarding.

“I’ve had really positive interactions,” Kramer said of working with GPP and other undergraduate students on Visualize. “The other part was certainly logistical. I was studying for my quals the semester I started working with them—so the idea of them helping out and being the actual hands that were doing the design work, where I could just do the mentoring and oversight, was really appealing to me. I also felt I had time to meet with them weekly, field questions, and give them more feedback than a busy tenure track professor would have.”

Fletcher Lab CellScope Is Ready for Scaling

By Lisa Bauer

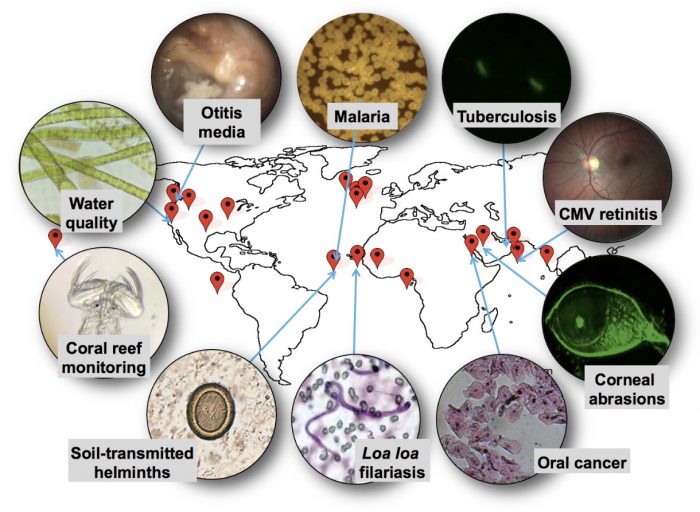

Nearly a decade ago, more than 80 global organizations came together to sign the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases, to control, eliminate, or eradicate at least ten of the diseases by 2020. Progress has been made on “NTDs” (neglected tropical diseases), but they still affect nearly one billion people, reinforcing poverty in low-resource regions.

UC Berkeley Professor of Bioengineering Dan Fletcher has been working to accelerate NTD diagnosis and treatment with a device so ubiquitous it’s probably in your hand: a smartphone. Fletcher, with a group of interdisciplinary scientists from in and outside his lab, have steadily proved that smartphone cameras can be repurposed as microscopes to identify disease-causing pathogens, such as the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and the parasites that cause River Blindness.

UC Berkeley Professor of Bioengineering Dan Fletcher has been working to accelerate NTD diagnosis and treatment with a device so ubiquitous it’s probably in your hand: a smartphone. Fletcher, with a group of interdisciplinary scientists from in and outside his lab, have steadily proved that smartphone cameras can be repurposed as microscopes to identify disease-causing pathogens, such as the bacteria that cause tuberculosis and the parasites that cause River Blindness.

“Phones have enormous imaging and processing capabilities,” explained Fletcher at a recent faculty salon of the Blum Center, where he serves as chief technologist. “Our work has been to harness these consumer electronics to do the complex imaging and image interpretation tasks. We add lenses and automation to the mobile devices; then we capture, geotag and upload the image data we collect, giving us greater information about the spread of disease.”

By removing the need for a laboratory and highly trained technicians to perform image-based processing, the Fletcher Lab’s CellScope, as the family of devices is called, can dramatically expedite NTD treatment by enabling patients to receive rapid, low-cost, and highly accurate diagnoses, even in remote regions. Fletcher and others believe the device has enormous potential to contribute to NTD elimination efforts, because while the drugs to treat NTDs already exist–an efficient, systematic, and affordable diagnosis and treatment method does not.

“Thanks to the London Declaration, major pharmaceutical companies have pledged to contribute the drugs needed to treat many NTDs,” said Fletcher. “CellScope will help us tackle the missing ingredient: the way to identify those in need. For effective treatment and monitoring, we must know who’s infected, where they are, and whether there is reemergence. That’s where technology comes in.”

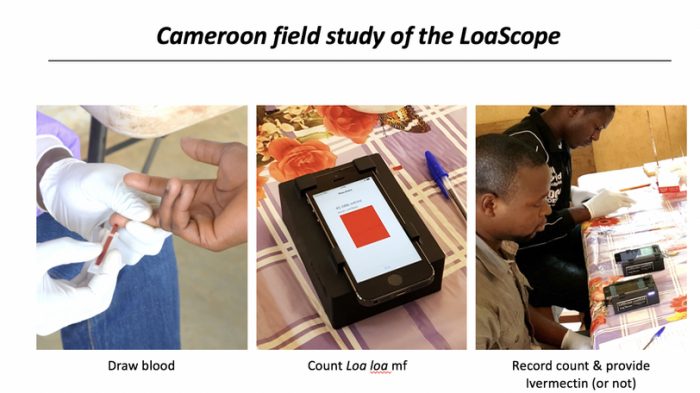

The latest version of CellScope, called LoaScope, has proven effective in Cameroon, where it is being used to combat a NTD called River Blindness or Onchoceriasis. Endemic in Sub-Saharan Africa, Onchoceriasis is a severely debilitating disease that results in human blindness. Although the antiparasitic drug, Ivermectin, is readily available, treatment via mass drug administration has been halted in some regions due to serious adverse effects caused by co-infection with a worm call Loa loa. Treatment in Loa-endemic regions is complex because if Ivermectin is administered to someone who is simultaneously infected with Loa Loa, the drug can lead to fatal complications.

To safely relaunch mass drug administration of Ivermectin, Fletcher and a team of medical professionals from NIH in the U.S., IRD in France, and CRFilMT in Cameroon launched a pilot project in Okola District of Cameroon, with funding from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Local healthcare workers collected small blood samples from patients and inserted them into the LoaScope to measure the number of parasites; if the number was below a certain safety threshold, then the patient was treated with Ivermectin. Patients with parasite loads above a certain threshold did not receive Ivermectin to reduce the possibility of complications from treatment.

With this approach, 96 percent of the 16,000 people examined in the Okola District pilot study had Loa loa levels below the safety threshold and were treated for River Blindness, while only 2 percent had to be excluded because of Loa loa levels that put them at risk of complications from treatment (the remaining 2 percent could not receive Ivermectin for other reasons such as pregnancy or illness). Findings from the Cameroon pilot were published in 2017 in the New England Journal of Medicine.

The Cameroon Ministry of Health approved the study and backed the use of the LoaScope technology to restart mass administration of Ivermectin for control of River Blindness. Prior to the pilot study, a public health education campaign to encourage citizens to seek safe diagnosis with LoaScope was carried out–including public testing of the Minister of Health with the LoaScope.

Although the Cameroon pilot was a success, the next challenge is scaling the technology so that the millions of people living in Loa-endemic regions can benefit from safe treatment of River Blindness with ivermectin.

“The problem is no longer that we don’t have the tools. We now do,” said Fletcher. “The problem right now is the funding, manufacturing, and distribution gap–how do we best scale this device and get it to the people who need it?”

Funds are needed to mass produce the device, establish a support infrastructure, and develop an IT system. Yet the cost benefits could be significant. For example, currently the cost of a single capillary for the LoaScope is $2; if the process was automated, the cost would decrease to just 30 cents. A similar reduction in cost of the device is possible.

In addition to River Blindness, the Fletcher Lab has identified five other NTDs for which CellScope could be applied. Schistosomiasis is the next disease the lab hopes to test and treat. Like River Blindness, schistosomiasis is a worm-based disease, but the parasites that cause it are detected in urine or stool samples. Thus, instead of taking a blood sample, CellScope would be adapted to analyze filtered urine and stool that is loaded into the same capillary and imaged with the same device.

“The basic technology–a mobile microscope with image processing capabilities–is already there, and with a few modifications we can adapt it to new diseases,” said Fletcher. “Increasing access to high-quality disease diagnosis is beginning to be within reach for low-resource settings with technologies such as these. But the same challenge remains: scaling.”

2018

2013 – 2014

2012

2010 – 2011

2009

December 2018

October 2018

DOST— Fostering Early Childhood Development in India

By Veena Narashiman ’2020

Early years of childhood form the basis of intelligence, personality, social behavior, and capacity to learn and nurture oneself. Increasingly, child development researchers are also finding that brain development during the first eight years is the most rapid, with children who receive attention in their early years achieving more success in school.

Sneha Sheth (Berkeley Haas MBA ’2016) knew these facts, having designed international programs for women’s empowerment and education for Dalberg, Education Pioneers, and Teach For India. She understood that early education in India was often neglected due to high rates of poverty and illiteracy–and that the nation holds many of the 200 million children in developing countries at risk of not reaching their full potential.

“I met hundreds of mothers, who had never gone to school,” said Sheth of her time working in a Mumbai slum. “They were willing to do whatever it took to get their kids a great education, but they weren’t really sure how. They would often ask me, ‘Well, I didn’t go to school, what can I really do about this?’”

While pursuing an MBA at Cal, Sheth began to think about an education technology project that could serve low-income Indian parents. During the summer of 2015, she and Sindhuja Jeyabal, who was completing a master’s degree at the UC Berkeley School of Information, piloted DOST, meaning friend in Hindi.

Sheth and Jeyabal then turned to the Big Ideas student innovation contest for development and feedback. Their Big Ideas mentor, Anthony Bloome, a senior education technology specialist at USAID, encouraged their ambition to come up with a solution for early childhood development in India. Big Ideas allowed Sheth and Jeyabal to iron out their implementation plan. In May 2016, DOST won in the Mobiles for Reading category.

Soon after, DOST was named one of the Top Three Edtech Startups in 2016 by the Unitus Seed Fund, followed by an invitation to join Y Combinator. In 2017, the team returned to Big Ideas, winning third place in the Scaling Up competition. The nonprofit’s supporters now include the Mulago Foundation, the David Weekley Family Foundation, and the Chintu Gudiya Foundation, among others.

The path to creating DOST was iterative, said Sheth. “At first, we talked to parents about how those who can’t read can still have a lot of weight in early childhood education. We had to show parents that playing, singing, and talking with their kids was a form of education.”

Sheth and Jeyabal recognized a major challenge was getting busy families to come to DOST early education classes. “You can’t change behavior in one session, and you can’t see changes penetrate in a community in just one session,” said Sheth. Even if one parent was able to attend sessions—and it was often the mothers—DOST wanted to involve fathers, grandparents, aunts, and other extended family members in lesson plans. When the team was brainstorming ideas for a practical approach to this problem, they finally asked, What if we just call them?

Due to the widespread use of Nokia cellphones, Sheth and Jeyabal began to consider a technological approach to parent learning. Sending podcasts to parents, they realized, would allow DOST to serve many families and grow rapidly. Parents also wouldn’t need to make the tough decision of deciding between attending a parenting class or cooking dinner.

DOST began to develop 1- to 2-minute daily lesson plans and verbal activities as podcasts deliverable to parents’ phones, allowing busy mothers and fathers to integrate their child’s early development into their daily lives. The audio programs instruct parents to teach basic literacy and numeracy. The first audio program is 24 weeks long, and is targeted at parents of children who are two- to six-years of age. As of October 2018, there are 20,000 Indian caregivers using DOST every day, a figure that has grown 100 times in the last two years.

One of the first lesson plans featured how parents could speak to their children without intimidation. By trying a collaborative approach rather than a violent one, parents reported their children were more receptive to instructions and guidance. One of DOST’s most popular mini podcasts encourages mothers to make rotis in different shapes for dinner—fostering pre-numeracy skills at a young age.

To build awareness for DOST, the nonprofit has hired mothers from the communities it targets. “DOST Champions see the untapped potential in their own community and know how to convince their neighbors to join DOST,” said Sheth. “It’s also a plus to create employment in the areas we work in.”

Ultimately DOST’s mission is to provide uneducated parents with the resources to enable their children to excel. “Whether it’s by categorizing rotis as big or small during cooking or naming the colors in a sari,” said Sheth, “these kids will be more prepared for their future.”

InFEWS Fellows Take on Sustainable Development Goals

By Tamara Straus

The goal of the PhD is to do original research in a specific discipline. That means in-depth and often narrow inquiries that build on academic knowledge. But for many STEM and social science graduate students, the great draw of the PhD is developing research that can have wide societal benefit—in clean water or pollution reduction, for example—and be implemented through government or business.

Since 2017, the Blum Center for Developing Economies has been enabling graduate students to develop societal benefit research through the InFEWS—Innovations at the Nexus of Food, Energy, and Water Systems—program funded by the National Science Foundation. InFEWS provides fellowships and travel stipends for students whose PhD research aims to provide lasting environmental solutions and alleviate poverty in the world’s poorest regions. The program’s mandate is to train a new generation of interdisciplinary STEM researchers and practitioners who can improve the living standards of Americans and meet the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The requirements are broad. InFEWS Fellows must address challenges at the intersection of food, energy, and water systems. Their research must take into consideration climate variability, water, and pollution, along with changing demographics in a world where the poor and rural have insufficient access to basic resources. To meet these challenges, InFEWS Fellows are asked to engage in interdisciplinary research activities and course work, including human-centered design and lean start-up approaches, as well as pursue immersive lab and field training. Students are also expected to gain experience in needs assessment, analysis of qualitative and quantitative data, and concept testing.

This year’s cohort of InFEWS Fellows includes 37 students from 13 schools and departments at UC Berkeley, including the School of Information, College of Natural Resources, Haas School of Business, College of Engineering, and Goldman School of Public Policy. Sixty five percent of the fellows are women and 25 percent are under-represented minorities, which is typical of STEM programs that address global challenges. In addition, 25 of the 37 fellows are also in the Blum Center’s Development Engineering program, which has similar goals in terms of training engineers who want to use technological innovations to address poverty.

Below are Q&As with four current InFEWS Fellows.

Sara Glade

Sara Glade is a PhD student in Environmental Engineering whose InFEWS work focuses on drinking water treatment technology development and implementation.

Sara Glade is a PhD student in Environmental Engineering whose InFEWS work focuses on drinking water treatment technology development and implementation.

Why did you seek to become an INFEWS Fellow and Development Engineering student?

My exposure to Development Engineering began during my undergraduate career when I was introduced to the organization Engineers Without Borders. I became deeply invested in the chapter, working on a water supply project in Haiti and a bridge project in Nicaragua. My passion for water came to fruition in the field in Haiti, after seeing children walk miles to collect polluted water. Here I learned the potential of engineering and water to improve the quality of people’s lives, which inevitably drew me to be interested in researching water treatment technologies for disadvantaged regions.

At UC Berkeley, I have been part of many social impact driven engineering projects. In the course DE 200, I worked with Sanivation, a container-based sanitation company located in Kenya. In CE 209, I worked with Berkeley-based startup SimpleWater to survey rural communities in California with arsenic contaminated drinking water about their water and point of use treatment. I learned first-hand the challenges communities throughout the Central Valley and the U.S. face with drinking water contamination. This ignited a strong interest in using Development Engineering to work on U.S. water issues, which I carried into my research. All of these experiences, before and during Berkeley, ultimately led me to the Development Engineering program.

Throughout my time at Berkeley, I have also grown to better understand and appreciate the link between food, energy, and water systems, and this drew me to the InFEWS program. My current research has also pushed me to think critically about these connections as well.

Tell us about your current research.

My current research started in quite a unique way. A UC Davis professor visited a community in the California Central Valley, in Allensworth, and met several community members looking for appropriate arsenic treatment technology solutions. This professor then contacted my advisor, Ashok Gadgil, because the Gadgil Lab has over 10 years of experience working on a novel arsenic treatment technology called ElectroChemical Arsenic Remediation (ECAR).

On our first call with several community leaders, we were asked to help treat water on their farm for a livestock application. The development of ECAR at small scale on this farm site would be a unique opportunity for economic development in the community, for fresh food to be available nearby, and could also enable next steps of a demonstration plant and community treatment plant for drinking water. I knew this project would be perfect for my interests in U.S. water, treatment technology development, and implementation.

Thus far, I have conducted lab scale tests to understand parameters useful in designing the field trial, have developed design constraints unique to the U.S. context, have discussed the field trial design with our community partners, and have presented our work to a number of stakeholders, including local nonprofits. The next step of this work is to finish raising funds, and then implement and operate the field trial. Alongside the field trial, I plan to conduct interviews with community members to understand their perception of this new technology. Overall, I hope to increase knowledge around appropriate drinking water treatment technology development and implementation in small, low-income communities in the United States.

What are your long-term goals?

After my PhD, I would like to continue working on development and implementation of water treatment projects, either in the U.S. or internationally, and could see myself working in low-resource regions on projects that are in between basic science and commercialization. It seems amazing technologies and research that could serve the needs of disadvantaged populations sometimes get stuck in papers or at small scale. I hope to work on bridging this gap throughout my future career, with the hopes of bringing to fruition many technologies that otherwise would stay trapped in a text. I am also considering doing a policy fellowship after my PhD. From the work I have done on U.S. water thus far, I have become very interested in how policy can prohibit or enhance access to safe drinking water in affected regions.

Christopher Hyun

Christopher Hyun is pursuing a PhD from the Energy and Resources Group with a designated emphasis in Development Engineering; his InFEWS work focuses on water and sanitation planning.

Christopher Hyun is pursuing a PhD from the Energy and Resources Group with a designated emphasis in Development Engineering; his InFEWS work focuses on water and sanitation planning.

What drew you to the InFEWS Fellowship?

What drew me to InFEWS is its community of learning. I’ve been working in the development sector for over a decade, gaining experience in income generation, capacity building, and water- and sanitation-related research. I’ve had the privilege of working with environmental organizations and institutions on water and sanitation, such as the Centre for Science and Environment, Banaras Hindu University, IIT-Bombay, and CDD Society in India. Sanitation is not often considered an important sector at the nexus of food, energy, and water, although FEW systems thinking has the potential to help solve sanitation’s challenges; so this is an opportunity for me to learn from other scholars in the InFEWS community. Also, I am currently observing a sanitation revolution occurring in the development sector about which I am excited to share with the community as innovations unfold, integrating with an increasing number of FEW systems. Furthermore, I enjoy contributing to discussions about the relationship between technological innovation and social structures as well as general social and governance perspectives of FEWS.

What are your overall research interests?

I recently completed a research project, working with water valvemen to help improve intermittent water systems and partnering with NextDrop and the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board. As I continue with my PhD research, I hope to uncover pro-poor sanitation solutions that have long-term impacts on food, energy, and water systems in urban contexts of low- and middle-income countries. I focus on the governance of sanitation in urban India, following decision-making by international funders and government officials as well as by the engineers who design low-energy intensive technologies (such as biogas digesters) and the local farmers who reuse the wastewater and fecal sludge. I am particularly interested in capacity building for innovative sanitation solutions and how capacity building is conceptualized and implemented across scales of governance in sanitation.

Why is capacity building so important in your research?

Local officials and engineers often don’t have the capacity to make design decisions, and farmers may oppose new sanitation systems as they would rather obtain fecal sludge directly (but unsafely) from septic trucks. In my research, I aim to understand such local dynamics and to uncover ways to mitigate the gaps between scales of sanitation governance. Capacity building is often considered a solution to such challenges. I partner with the Consortium for DEWATS Dissemination (CDD) in India, internationally recognized for innovations in low-cost sanitation systems, reuse, and capacity building. I have worked closely with CDD, designing and implementing sanitation training focused on CDD’s “toilet to table” philosophy. In research, I utilize an ethnographic approach, conducting observations and interviews with stakeholders, civil society organizations, and government officials. My goal is not only to uncover how capacity building can be more effective, but more fundamentally how capacity building is being defined and implemented, including by whom and for whom. Uncovering capacity building not only informs development practice but it also helps us understand how and why technological transitions may (or may not) happen, which I believe is at the heart of both Development Engineering and InFEWS.

George Moore

George Moore is a Mechanical Engineering and Development Engineering doctoral student whose InFEWS research focuses on food, energy, water systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation of Northern California.

George Moore is a Mechanical Engineering and Development Engineering doctoral student whose InFEWS research focuses on food, energy, water systems with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation of Northern California.

What drew you to research on sustainable energy and water resources?

My first opportunity to work on InFEWS-related research came during my summer research internship at the University of Michigan in 2015. There, I studied a sustainable manufacturing project for an underdeveloped community in Uganda. Reflecting on my own experience growing up as a minority in the rural South, this project made me feel personally connected and empathetic towards underserved communities globally. I read about several case studies where organizations or researchers engaged with communities in developing countries and the original plan of action had to be altered to accommodate for context and cultural values that could not have been foreseen. Although this seems obvious to me now, I was surprised and grew curious about the methods used to design for communities like these in ways that would precipitate not only tangible goods, but also sustainable practices related to the handling of primal needs like food, water, and energy resources.

How did you come to work with the Pinoleville Pomo Nation (PPN) of Northern California?

As a PhD student working with Professor Alice Agogino and two other graduate students, I helped plan field research conducted at the PPN’s annual Big Time festival in Summer 2017. There, we were able to observe and engage with the PPN community in their own sacred environment. In addition, we provided an exercise that encouraged PPN members, and others in attendance, to articulate their opinions of the current problems within the PPN community as well as potential solutions to those problems. We offered five suggestive themes to categorize these responses, in which most of them cater to the vision of the InFEWS initiative: Food, Water, Energy, Education, and Well Being.

Since then, we have continued to work with PPN community leaders to establish how to progress with a project that would align the needs of the PPN community with those of our research goals. The PPN community has expressed interest in STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math) Education, and over the past year has started an Academic Success Center, invested in a makerspace, and finished the second year of its annual STEAM summer camp. With this in mind, we have re-framed our research scope to emphasize InFEWS themes within the context of STEAM education and the design of culturally sensitive makerspaces.

What are your long-term goals?

I’m genuinely excited to be working on a project that aligns so much with my personal and academic goals. I think that success for the PPN project requires our roles as facilitators to become obsolete—creating lasting change that will continue long after our presence is removed. Also, we hope that whatever is produced from this collaboration upholds the values of the community. To achieve that goal, we have been careful to minimize the ideas and subtle influences that we might impose as researchers.

Lorenzo Rosa

Lorenzo Rosa  is a PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management whose InFEWS research investigates where water scarcity may limit energy and food systems.

is a PhD candidate in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management whose InFEWS research investigates where water scarcity may limit energy and food systems.

How have your academic interests informed your InFEWS work?

My training is in engineering, hydrology, and energetics. Before pursuing a PhD at UC Berkeley, I received master’s and bachelor’s degrees in Environmental Engineering from Polytechnic University of Milan, Italy and studied abroad at KTH Royal Institute of Technology and the University of Virginia. Since 2017, I have been awarded an Ermenegildo Zegna Founder’s Scholarship. Over the years, while studying the chemical processes of engineering as they relate to the environment, I noticed that the biggest environmental polluters are the food and energy sectors. This got me thinking I should focus on energy and food systems and hydrology to develop a framework using water balance.

Why focus on water balance?

An often-overlooked aspect of water requirements for economic activities is that water is a limited resource and some of these activities could be constrained by water scarcity to the point of limiting the development of some assets. For instance, lack of water resources can impede the extraction of some minerals, the generation of electricity from coal fired and solar power plants, the production of biofuels, or the closure of the yield gap in agricultural land. In all of these cases, water scarcity might be a limit to these activities.

While substantial additional water will be required to support future food and energy production, it is not clear whether and where local freshwater availability is sufficient to sustainably meet future water consumption. The extent to which irrigation can be expanded within presently rain fed cultivated land without depleting environmental flows remains poorly understood. It also remains unclear where and to what extent new water demanding energy projects, such as post- combustion CCS and hydraulic fracturing, might be constrained by local water availability.

How does your research on water scarcity differ from other assessments?

Previous efforts have assessed the water footprint of energy and food systems from the life cycle assessment perspective, focusing on a comprehensive accounting of all water costs associated with production and processing, but without examining the availability or source of the required water. The novelty of my research consists in the assessment of the impacts of energy and agricultural systems on the local water balance using a hydrologic approach, identifying the regions in which new forms of potential water consumption from the energy sector could compete with agriculture and other human activities, and areas in which water demand from energy and/or food systems could not be sustainably met because of water scarcity.

I believe neglecting water availability as one of the possible factors constraining the development of economic activities may lead to unaccounted business, social, and environmental risks. By adopting a hydrologic perspective that considers water availability and demand together, my aim is that decision makers, investors, and local communities can better understand the water and food security implications of energy and agricultural production while avoiding unintended environmental consequences.

Tell us about your dissertation work.

My dissertation will provide a quantitative framework to make informed investment decisions involving natural assets that are susceptible to water risks. As such, I am currently investigating where water scarcity may limit hydraulic fracturing and food production–thus creating risks for local populations and investors. My goal is to identify global hotspots of where human activities compete for water allocations, potentially creating social, environmental, and economic risks. My belief is that the limited understanding of the potential impacts of human activities on water resources prevents the implementation of a sound management plan for a sustainable human development. For example, we are depleting ecosystems in rivers because we are taking too much water from them. The classic example is the Colorado River. It runs dry and the water does not reach the ocean. Another example is non-renewable ground water mining. Water that was stored millennia ago is being used unsustainably in India, Pakistan, and Central California, among other places.

They key is understanding where we can increase water production, because we know the population is going to reach 9.5 billion by 2050. We’ll need to add 50 percent of current water production to feed all these people. And so we’ll need to figure out where we can (and cannot) produce more food with water in a sustainable way. In other words, we’ll need to move production where the water is or swap crops or use less water-intensive crops or transport water—so that we can increase food production for 2.8 billion people.

The InFEWS program is supported by the National Science Foundation (infews.berkeley.edu ; DGE # 1633740).

Multiplicity Not Singularity: Ken Goldberg on the Future of Work

By Lisa Bauer

Robotics Professor Ken Goldberg is the first to acknowledge the public anxiety about what automation and AI might mean for future jobs. Singularity—the hypothesis that AI will become increasingly powerful, decimating professions and remaking civilization—is becoming a mainstream concept. All one has to do is read news headlines about robot-driven factories, watch movies like “Ex Machina,” and listen to public figures like Elon Musk stating that AI poses our greatest existential threat.

Yet at a recent Blum Center Faculty Salon on the Digital Transformation of Development, Goldberg, UC Berkeley’s Department Chair of Industrial Engineering and Operations Research and the William S. Floyd Jr. Distinguished Chair in Engineering, argued that such fears are exaggerated. He is among computer scientists and roboticists who believe there is inadequate evidence to support the mass unemployment theories, such as the often cited Oxford University study that estimated 47 percent of U.S. jobs are at risk of computerization.

Rather than replace human jobs, Goldberg believes artificial intelligence and robots will help to diversify human thinking. And rather than worry about a robot apocalypse, he urges a focus on what he calls Multiplicity, in which diverse combinations of people and machines work together to solve problems and innovate.

“Multiplicity is not science fiction. It’s a reality that is already a part of our daily lives,” said Goldberg.

To prove his thesis he references Google search, Amazon and Netflix’s personalized consumer recommendations, Waze navigation, and spam filtering—examples of machine learning that lead to rapid, wide-scale results. One of Goldberg’s points is that the public has long held a fascination with “creative overreach” and mechanized monsters (e.g., Pygmalion, Frankenstein, the Terminator). Yet our greatest AI successes so far have not involved walking, talking robots or even autonomous vehicles—they have involved machine learning for games, such Google DeepMind’s mastery of chess. This is because machines excel when operating in a controlled information system; whereas navigating space is dynamic and uncertain.

Goldberg said the race to develop fully autonomous vehicles exemplifies this misunderstanding. While the public has been led to believe that autonomous cars are just a few years away, engineers and computer scientists say there are many barriers to overcome because driving is not a game with set variables. It involves navigating double parked trucks, weaving bikers, kids playing, and shade and light obscuring vision. A computer program is currently not capable of responding to these myriad, unpredictable situations. Indeed, Goldberg argues we are just as likely to be headed for an “AI Winter” rather than a near future with driverless cars.

Goldberg believes that automation will both eliminate and create new jobs. Quality of work may be improved by decreasing the amount of time spent on mundane tasks. One example of this is the ATM machine, which was initially met with outcry from bank tellers who believed their jobs were doomed. Instead, the lower costs of running a branch allowed banks to open more branches and expand services, ultimately increasing the number of overall jobs while also creating new types of jobs in sales and customer services.

“People are claiming that AI will steal truck driving jobs,” said Goldberg. “but the fact is we have a shortage of truck drivers and there’s demand for more. Technology will make their jobs better.”

Proceeding further, Goldberg compared automation anxiety to anti-immigrant politics, quoting Oliver Morton’s observation that “robots are immigrants, from the future.” Historically, job losses have been blamed on immigrants; today said Goldberg, robots are the latest scapegoats.

“We need a shift in mindset, rather than ‘us against the machines,’” emphasized Goldberg. “let’s focus on ‘us with the machines,’ and explore the potential for machine collaboration—how the combined strengths of diverse humans and diverse machines can enhance the human experience.”

“Cognitive Diversity, AI & the Future of Work,” a study co-authored by Goldberg and Vinod Kumar, CEO of Tata Communications, reports that much of education today emphasizes conformity, obedience, and uniformity, while the skills of tomorrow demand creativity, diversity, and flexibility. Most of the 120 global business executives interviewed for the study believe AI will increase the number of roles in the workplace and have the potential to enhance human collaboration and cognitive diversity within groups. Among the report’s conclusions is that what we need is not new forms of welfare and unemployment, but a shift in education that will better facilitate job transitions.

Goldberg said advances in agricultural machinery at the beginning of the last century prompted a need to train people with non-farming skills, creating what would become the “High School Movement.” The impact was huge: in 1910, only 10 percent of Americans graduated from high school; by 1950, 80 percent held a high school degree.

Given this precedent, Goldberg proposes a “Multiplicity Movement” to foster uniquely human skills that AI and robots cannot replicate: creativity, curiosity, imagination, empathy, human communication, diversity, and innovation. He recommended the U.S. reinforce creative and social skills in high schools and universities, so that Americans are in position to leverage diverse machines alongside diverse groups of people to amplify intelligence and spark high impact problem solving.

In response, Laura Tyson, Blum Center chair and interim dean of the Haas School of Business, expressed greater apprehension about the effects of artificial intelligence on the future of work. She emphasized that each country and region will experience the digital transformation differently, according to factors like local policies and politics, demographics, and educational attainment. Tyson, who has years of policy experience in the U.S. federal government and international organizations, pushed the group to think more broadly—not just in terms of the future of jobs but also in terms of what she called the “future of livelihoods.”

“Individual workers should not have to bear the costs of transitions from jobs that are eliminated by technology to jobs that are created by technology,” she said. “We need to ensure that livelihoods are not compromised in the transition, and that we are counteracting rather than reinforcing economic inequality.”

Tyson contrasted concerns about the effects of AI on the future of work in the U.S. and other developed countries with the enthusiasm for AI in China where “automation anxiety” hardly exists. As a result of the largest and fastest industrialization and urbanization in history, China has a growing and thriving middle class that is heavily reliant on new technologies. Based on the rapid growth in living standards over the past 30 years, Chinese citizens expect that they will continue to benefit from new AI-based technologies.

The substitution of intelligent machines for low-cost, low-productivity workers poses the greatest challenge to the future of livelihoods in Africa. Such machines threaten the strategy of rapid development through industrialization based on low-labor costs and labor arbitrage. By 2050, Africa’s youth population is estimated to increase by 50 percent to 945 million. The continent will have the largest number of young people in the world. What kinds of work will they do? What kinds of livelihoods will be possible? What will be the place of African countries in global trade and global supply chains when the availability of comparatively cheap labor is no longer a competitive advantage?

Juxtaposing the youth explosion in Africa, the aging demographic patterns in Japan and Germany, the U.S.’s skills and wealth gap, and the success of China in rapid industrialization and global trade, Tyson posed several questions to consider: How will we ensure that all countries and communities benefit from AI and automation? How do mid-career professionals adjust if their job becomes obsolete? How will mid-career professionals gain new skills? Who pays for it? How do we prepare diverse populations for smooth economic and labor transitions?

Tyson advocated that nations develop comprehensive educational and development strategies that support the livelihoods of their citizens—and that share the benefits of intelligent machines broadly.

Computer Science Has the Power to Impact the Lives of the 99 Percent

By Divya Nekkanti

During high school, I looked unquestionably at technology leaders like Bill Gates and his wife Melinda, whose philanthropic foundation aimed to solve every apparent misfortune in the Global South. Even more, I found solace in the “giving back” days that Silicon Valley tech companies employed as a fulfillment of their corporate social responsibility.

During high school, I looked unquestionably at technology leaders like Bill Gates and his wife Melinda, whose philanthropic foundation aimed to solve every apparent misfortune in the Global South. Even more, I found solace in the “giving back” days that Silicon Valley tech companies employed as a fulfillment of their corporate social responsibility.

But increasingly, no matter where I look–in the world, in my community, within myself–tech and development are misaligned. There seem to be two mutually exclusive avenues of engaging with the world–innovating or giving–the only overlap for which involves donating money to admirable causes or engaging in occasional volunteer service. This dichotomy between the fast-paced, disruptive tech world that doesn’t afford engineers the time to fully understand the complexities of social challenges and the slower-moving development sphere, where the redundancy of approaches and lack of human, financial, and tech capital hinder growth, have become more and more apparent to me in my experiences at Cal.

Perhaps this dichotomy was once not so strong, but as an Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) major today there’s a very distinct path you follow. You take onerous math and programming classes, cease at nothing to get accepted into the engineering or business consulting organizations that flood Sproul Plaza in the semester’s first few weeks, and then embark on a toxic pursuit of software engineering internships at Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Salesforce, Amazon, etc. You attend every info session, stand in hour-long lines to talk to a single recruiter, and apply to hundreds of companies without distinction as to why–all because the sole purpose of your “technical” education is to work at the biggest, most profitable software company in the Valley.

Application of knowledge becomes fixated on the destination rather than the journey, and despite going to a school as economically and experientially diverse as Berkeley, you get so lost in the allure of free T-shirts and food, the glitz and glamour, that social problems–even at the campus level–go unnoticed. Despite having few requirements outside the EECS major, the exhaustion from technical courses prompts you to deliberately pursue humanities courses that offer the highest average grade and lowest workload, rather than taking classes that actually pique your interest.

Disillusioned by this herd mentality and eager to explore a multidisciplinary Berkeley education, I decided to pursue a minor in Global Poverty & Practice. Taking on this minor was the best decision I made at Cal, as it is affording me an evaluative lens not only to examine determinants of poverty, but for the first time to critically analyze the bubble I have been living in for my entire life in Silicon Valley. A productive hiatus from my homogenous computer science courses, GPP is allowing me to daily interact with students from a broad array of majors and backgrounds, whose perspectives challenge my own and elevate every classroom discussion.

Yet despite the minor’s longstanding diversity, I see few engineers, even fewer computer scientists, in my GPP classes. At the same time, across campus I see few engineering and computer science students willing to confront the economic misfortune and inequality of access that exist beyond Soda Hall. With my eyes more open than ever been, I can now critically assess a variety of complexities: the tax evasion benefits and occasional alternate agendas behind philanthropic donations; the dependencies that result from inconsistent foreign aid; and the millions of laptops donated by the tech community’s One Laptop Per Child program, which never reached children in need.

Unlike the abundance of engineering courses that posit innovation must be accelerated to be disruptive (thus often fabricating problems to “solve” and oversimplifying ones that already exist), GPP courses are making me careful about my language, as I “practice” how to effectively address people in poverty (rather than naively think I can “serve” them).

Never anticipating the ability to reconcile my passions for tech and development, last summer I intentionally took on two very different internships: one with an NGO that focuses on education, economic empowerment, and equality for women and girls in developing regions; and the other an analytics consulting company.

At the NGO, I actively tried to refrain from imposing my software skills, as I was wary of oversimplifying the problems the nonprofit inwardly faced and outwardly worked on with redundant tech solutions. Yet day after day, the need for tech internally to scale the organization and externally to enrich the organization’s education programs, felt glaringly critical.

My most surprising discovery was the NGO’s high turnover, which appeared to engender bottlenecks like lack of data standardization. As employees came and went on their own volition, they stored years of donor and program information on different online services, in independent accounts, and with inconsistent formats. The irregularities on this scale of data made communication with donors and tracking of scholarship students nearly impossible, with half the incoming mail consisting of emails undeliverable as addressed. Seeing as the NGO was primarily funded by donors, the gravity of mismanaged data heightened by the day.

Even more of a hurdle was the lack of technology for educational programming and outreach. While the organization received Chromebook donations from Google, low electricity in the areas where the NGO work prevented deployment of the laptops. And while the girls finishing high school requested technical curriculum in robotics and web development, there was no one with the bandwidth to structure the programs. Meanwhile, in my second internship at the analytics consulting company, the resources seemed endless. If I didn’t like the size of my Mac, with a few clicks I could instantly order a new one. Unlike at the NGO, where I knew the faces and names of the women my work was directly affecting, working on software projects at a large tech company felt like coding in a black box. I was assured there were huge companies on the other end, transforming their businesses with the firm’s services, but my role in delivering this value was largely ambiguous and concerns were cursorily dismissed.

It was only during my practice at the nonprofit that I began to view challenges of sustaining an NGO and achieving development goals as technical opportunities. Sourcing data from all accounts, I wrote scripts to parse CSVs and standardize entry formats, transitioning the entire organization onto Salesforce’s nonprofit success pack for centralized donor and program management. I researched solar chargers and the historical reception of robotics and web development curricula in the NGO’s target regions, wrote cost/benefit analyses, and developed technologies for later deployment in schools.

With every task I completed and every proposal I pursued, I realized how invaluable technology in the social sector has the potential to be, especially in streamlining internal processes and scaling external facing projects. Connecting the two disparate dots in my life, I have felt fulfilled and inspired. I have realized innovation isn’t solely synonymous with the next iOS update, computer science has the power to impact the lives of the 99 percent, and the “technical vs. nontechnical” mentality we unconsciously employ fails to represent the very multifaceted and interdisciplinary approaches requisite in development.

As an engineer, I have gleaned that it is possible to transcend the stereotypical boundaries of a traditional tech job, that it doesn’t take the philanthropic capital of a billionaire to change the world, and most importantly that I don’t need to compromise my technical background to alter paradigms in the development sector. Instead, I can actionably address the assemblage of social issues that keep me up at night with the skills I learn during the day.

Divya Nekkanti ’20 is a UC Berkeley Electrical Engineering & Computer Science major and a Global Poverty and Practice minor from San Jose, California.

Can There Be A National Security and Development Agenda for the U.S.? Michael Nacht at the Blum Center

By Tamara Straus

On October 10 at the first Blum Center Faculty Luncheon devoted to “Digital Transformation of Development,” Michael Nacht, the Thomas and Alison Schneider Chair in Public Policy, presented on “The Nexus of National Security, Diplomacy, and Development”—and gave a sober assessment of what that nexus might produce under the Trump administration.

On October 10 at the first Blum Center Faculty Luncheon devoted to “Digital Transformation of Development,” Michael Nacht, the Thomas and Alison Schneider Chair in Public Policy, presented on “The Nexus of National Security, Diplomacy, and Development”—and gave a sober assessment of what that nexus might produce under the Trump administration.

Nacht, who has served three tours of duty in government, most recently as Assistant Secretary of Defense for Global Strategic Affairs (2009-2010), provided an overview of government investments in the defense and development sectors. He reminded the group of Blum Center-affiliated faculty that the research which led to the atomic bomb was entirely government funded and led through national labs, including Lawrence Livermore National Lab.

“Thinking about it now years later,” said Nacht, “the community that makes up Lawrence Livermore National Lab understands things have really changed. There has been a proliferation of technologies and the vast majority of the innovative work is being done by the private sector. In fact, 85 percent of the research and development in this country is being funded by the private sector, not the government. It has spillover effects, not just in national security, but in development.”

Nacht was referencing a 2018 LLNL book on this shift he co-edited entitled Strategic Latency: Red, White, and Blue—Managing the National and International Security Consequences of Disruptive Technologies. The book looks at the implications of artificial intelligence, bioengineering, and other technological advances and underscores the consequences of disruptive paths are never straight. “We appreciate the seeming contradictions that can lead life-saving technologies in unintended negative directions, or prompt military technologies toward peace and prosperity through spinoffs or war-avoiding defenses,” Nacht and his co-editor Zachary Davis write in their introduction.

Yet Nacht has become a pessimist. He said that national security and international development interests don’t have much current geopolitical overlap. That is because national security interests are focused on Russia, China, Iran, North Korea, Islamic terrorism, cyber threats, and space-related work—and international development interests are focused on areas of high poverty, particularly Sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia. “Really, the only two [developing] countries that transcend to the national security community are India and Iraq,” he said.

Also, Nacht is adamant that the current presidential administration is making defense, diplomacy, and development intersections unlikely because of what he called “the Trump team’s tremendous rejection of multilateral instruments.” He added: “There may be outright hostility in trying to apply national security interests to international development interests.”

Nacht did point out the Department of Defense under former Secretary of Defense Ash Carter (2015-2017) focused on strengthening ties between the DoD and the tech community. In August 2015, DoD established the DIUX, the Defense Intelligence Unit Experimental, with headquarters in Mountain View, to help the U.S. military make faster use of emerging commercial technologies, promote joint appointments, and imbue the defense department with a more entrepreneurial culture. Nacht said those efforts have not ceased, but it is unclear whether they are, or can be, a priority under Secretary of Defense James Mattis.

Still, Nacht pointed out that we will continue to see areas of confluence between defense, technology, and even development, especially in academia. He cited the example of UC Berkeley Bioengineering Professor Jay Keasling, whose research on the metabolic pathways inside cells led to a semi-synthetic version of the antimalarial drug artemisinin, which has driven down the cost of treatment and saved lives in Sub-Saharan Africa, creating greater equity and stability.

Yet Nacht expressed concern that new technologies, particularly AI and machine learning, could devastate the developing world. Citing a September 17, 2018 Bloomberg article on the subject, he said China has been able to leverage its large population and low costs to build a manufacturing sector that is producing better and more technology-intensive goods—while India, with its large English-speaking population and low costs, has become a hub for outsourcing low-end, white-collar jobs in fields like business-process outsourcing and software testing. Now, however, with AI’s accelerating automation of factories and customer service, corporations will bring many of these jobs back to where they are based, leading to a potentially explosive crisis.

“It’s a complicated pattern,” said Nacht. “Using technology to improve lives sometimes works and sometimes doesn’t.”

At the same time, Nacht noted that China’s investment in African and Latin American infrastructure in exchange for natural resources is a phenomenon that the U.S. cannot afford to ignore, especially as China does not proffer democracy building, human rights, or other political carrots as a condition for investment. This purely economic transaction, Nacht said, is one that the Trump administration might follow, ending decades of foreign policy initiatives.

Nacht concluded that the U.S. needs more strategic interaction between its economic and foreign policy positions in developing countries, but said reading the Trump administration’s tea leaves in this regard is next to impossible.